- Home

- Ralph Peters

The Damned of Petersburg Page 17

The Damned of Petersburg Read online

Page 17

The thing to do, of course, was to prove he deserved it.

“Think they’ll come again, sir?” an officer asked.

“They’ll come again,” Girardey said. “And we’ll knock them back again.”

“Too damned hot for this,” a soldier noted.

Eleven thirty a.m.

North of the Darbytown Road

Brigadier General Alfred Howe Terry disliked displays of temperament. So he had refused to blow up on anyone after his division’s first advance ran into a pond none of Hancock’s people had mentioned. Of old Connecticut blood, Terry preferred solutions to theatrics. And when his second probe went forward and found Rebels and ravines where none should have been, leading to a second repulse, he took that in stride, too. Nor did he offer excuses when his corps commander, Davey Birney, chided him to attack again at once. He quietly demurred and saw things done properly.

Birney wasn’t a bad sort, but he wasn’t a Yale man.

Terry grasped how to do the thing now, and that was all that mattered. He’d always taken pride in craftsmanship, whether carving scrimshaw as a boy, practicing law in New Haven, drilling militia, or in the throes of battle. A New England gentleman held his tongue and let his work speak for him. And he was about to strike a resounding blow, one that would satisfy Birney and deliver a gentlemanly retort to Hancock and his deified Second Corps.

The army’s champion, “Hancock the Superb,” had botched things three days running. The poor old fellow survived on reputation. Nor had his ever-lionized subordinates done well. Birney’s Tenth Corps, by contrast, always seemed to be slighted. Now Terry meant to achieve what Hancock and his corps had failed to do: break the Confederate lines and send the Rebs reeling.

It was all a matter of paying attention, whether to points of law or to the details of the terrain. It had taken some hours and losses, but he understood the ground and the Reb dispositions. He believed he saw the weak point in their defense. This time, he’d hit them with three brigades, the two on the right echeloned for a double blow, with the Western Brigade leading, formed on a narrow front behind a copse, a surprise for the Johnnies.

It was largely mechanics, really. Move swiftly with maximum force over the shortest possible distance, converting volume to power through concentration. Calculation, not gush, that was the thing. And remember your men are human. Spare them from the heat as long as possible. Study what lay in front of you. Give clear orders and see that they’re obeyed. Then hit a blow as hard as you can deliver. No need for any fuss.

As the last of his men formed up, the Rebs poured on shot and shell as if dreading the future, firing blindly and guessing at the range.

Terry strolled over to Hawley’s brigade and told a covey of officers:

“No need to display yourselves, gentlemen. Everyone knows you’re brave. Have your men lay down until we’re ready. And take cover yourselves.” He smiled as fully as heritage permitted. “Believe I’ll take a tree myself. Bad form to fall on our side of the lines.”

And there it was: the supporting cannonade he’d asked of Birney. The sound of guns well tended always inspirited Alfred Terry. He stepped out to have a proper look and found the cannoneers were doing splendidly. Barely exposed, a Reb breastwork nonetheless took a direct hit. Then it suffered another.

One had to feel for the fellows on the other side. But not too much.

He took off his hat and patted his face with a handkerchief doused with cologne water. Another sweltering day. Hard on the men’s spirits. But he’d seen that they all had full canteens for the attack, and no excuses. Give them a taste of victory and they’d be fine.

Terry looked at his watch, waiting for word that his last brigade was ready.

Noon

Darbytown Road

The Yankees burst from the trees. More of them than Girardey had expected. His Georgia brigade was stretched thin and he felt a moment’s alarm. But his men were intent and ready, steadying their rifles on berms and rails. And the ground was broken, a mess of felled trees, stumps, and stumble-holes, a trial for any attacker.

“Hold your fire,” the new brigadier cautioned. “Officers, let them get close.”

The first two Yankee advances had been halfhearted, barely annoying his section of the line. Their numbers were greater now, but he doubted that their resolve was much increased. The Federals wilted fast in the Southern heat.

“Let them get close,” he repeated in a lower voice. Revolver in hand, he pressed closer to the earthworks thrown up in haste.

One good volley. And Victor Jean Baptiste Girardey believed the Yankees would fold their hand again.

Coming on fast, though. Pushing through the obstacles with a will. Hurrahing.

One good volley. And they’d shut their mouths.

Coming fast.

“Ready! Take aim! Fire!”

His line erupted in spurts of flame and smoke. He heard mad groans and cries. And the urgent clanking of his soldiers’ ramrods.

The Yankees would give a volley. Then they’d run. Just how they behaved.

But as the smoke wisped off, Girardey was shocked. Hurrahing anew, the Yankees didn’t pause to return the volley but ran hard for his line, bayonets fixed.

It all went too fast. The first Yankees leapt over the ragged parapet before his men could reload. Blue coats and caps plunged among them, thrusting bayonets. Rifles blasted chests and faces, bellies and groins.

His men hadn’t fixed bayonets and tried to do so now. Girardey fired his pistol once, then paused, frustrated by the melee, fearing he’d hit his own men. As he watched, dumbstruck, a Georgian swung his rifle by the barrel and the stock hit a Yankee’s jaw so hard it tore it from the man’s face. Bayonets lifted the hellion off the ground as blue-bellies cursed him.

His men began to turn and run. Some threw down their weapons.

All this in seconds.

Girardey found his voice: “Stand, boys! Stand, for God’s sake! We have to turn them back!”

A bullet struck the center of his forehead.

Twelve fifteen p.m.

Clarke house, Union Tenth Corps headquarters

The smarmy bastard had done it! Major General David B. Birney could only lower his field glasses and shake his head in wonder. Terry had broken the Confederate line in the blink of an eye. His troops, climbing the hillside, seemed unstoppable.

Terry. A fellow with no more swagger than a fence post. Impossible to befriend and imperturbable. The saltbox sonofabitch had really done it.

Now Terry wanted support. Birney turned to his nearest aide.

“Go to my brother. Tell him to advance his division immediately. He’s to follow Terry’s bunch. And keep on going.”

To a nearby major he added, “Crandall, take down a message for General Hancock. Be quick, man. The slavers are running. He’s got to bring his corps into the attack. Put it politely, but make it clear.”

Birney intended to make his breakthrough stick.

Twelve twenty p.m.

Darbytown Road, Robinson farm

Ticks. Everywhere. Major General Charles Field disliked the fiendish creatures, but he’d grown weary past caring. Hardly snatched an hour of sleep in the night, at it like a field boss before dawn. He’d gotten the reinforcements set in right, though, Sanders’ and Girardey’s brigades, on loan from Billy Mahone. And they’d whupped the Yankees handily.

He dozed, but willed himself to stay in the shallows, war-trained not to let himself drift off. Alert to the snap of rifles and shouting down the hill, he ignored the rustle of staff men slipping into the cornfield on private business.

The shade was a seductress, though, a Jezebel. That hint, if nothing more, of coolness on a torrid day felt precious. He was a proud man, Charley Field, proud of his work this day, with the Yankees repulsed handily, and proud of the way he’d handled Hood’s old division since he’d gained its command in the winter.

Yankees were at it again now, back for a third helping. He knew how to read t

he firing and not flare up like a fool at a few huzzahs. The position his men held was strong, much of it concealed. The Federals were hurling men away like a drunkard squandered silver.

A mosquito bit him on the back of the neck.

If men had any decency, Field concluded, they’d outlaw war in the months of July and August. The heat just took a man down. Thirty-six years old, hardly a Methuselah, he felt as though he’d been dancing all night with bobcats. And his wound from Second Manassas was in a temper.

Mahone’s men on detachment had straggled in during the night, weary and parched. They did know how to fight, though. Sanders was strong, always had been, according to campfire lore. And the new fellow, Girardey. Well, they’d just have to see. Bound to be many a jealous colonel, with that boy jumped up from captain to brigadier general. He’d have to weather that. Pretty little fellow. French, though he didn’t sound it. Well, Girardey had held his own so far.

Field spit a fly away from his lips and remembered. All the dead, the friends lost. Class of 1849 hadn’t shamed West Point, but it hadn’t been lucky.

A few more minutes and he’d need to rise. Have a look around, let the soldiers know he was watching over them. The Yankees were still at it down the hill, but more fool them. Hadn’t made one gain stick in three days of trying.

He sighed. Wondering how many ticks he’d pull off that night.

His nephew and adjutant, Willie Jones, called out, “General, they’re breaking.”

Field blinked once, then shuttered his eyes anew against the brightness. “Damned right, they’re running. What did you expect?”

“No, sir,” Willie yelled, all hot. “It’s our men. Our men are running.”

Devil in a pickle jar … what the roaring hell? Field levered himself to his feet so fast it left him dizzy.

“Look!” Willie called.

His staff had rushed to the edge of the little plateau, where the road dropped toward the fighting. Field joined them.

And he saw a sight to make a man sick and bust his heart twice over. His own kind, soldiers under his command, came scampering up the hillside. More than a few had thrown away their rifles.

“Blind me, Jesus,” Field gasped.

An aide exclaimed, “Yankees! Right down there!”

Field drew himself together. “Who’s running? Can you tell?”

“It’s those Georgians.”

Mahone’s bunch. Girardey’s lot. That overpromoted captain would have some explaining to do.

“Well, stop them,” Field said. “Corbin, take charge. Pistols out, gentlemen.” Then he added, “Don’t shoot, unless you have to. Just turn them around, form a line.”

He called for his horse and barked orders at his couriers, sending three of them off to find reinforcements wherever they might be had. To a fourth man whose horse had been killed, he said, “Sergeant Powell, go right overland, go southward. Tell every ranking officer you meet that we need help, they’re to strip the lines. Go, man, run!” And to his nephew he said, “Willie, Lee’s on top of the hill. Go find him. Tell him the devil’s got loose.”

Then Field and his staff stepped into the roadway, revolvers drawn, calling on men—some by name—to halt and fight.

The soldiers ignored their words and their pistols alike.

Twelve thirty

Darbytown Road

“Go back,” Lee begged, “go back! We must drive those people, push them back. Rally, men, rally. Do not let your fellows down. Go back…”

Few heeded him.

Lee sat on his horse in the middle of the road. When men spotted him, they shied, easing out into the fields. But they continued to flee.

“Soldiers! Remember your pride, your homes … your country. Turn and fight, turn around. We must retake those works … remember yourselves…”

At the Wilderness and again at Spotsylvania, his appearance had been enough to staunch the flight of men shocked into panic. Instead of retreating farther, they had seized his bridle, insisting that they would fight if he went back.

This day … mortified him. Some soldiers turned about at his behest, but such were few, too few. He feared he had lost his gifts, perhaps his army.

The sounds of battle approached—those horrid Yankee cheers—and Lee’s dismay became anger. He nudged Traveller into the path of a black-bearded man stumping dead-eyed toward the rear.

“You there!” Lee called, voice changed to one of command. “Where are you going? Aren’t you ashamed, sir? Disgracing yourself…”

The dead eyes changed to doleful and the soldier lifted a much-tormented hat, grimacing in sudden pain as he did so.

The man’s scalp was torn and hanging, the skull exposed.

He replaced his hat and walked on.

His men. These men. Such men …

Lee turned his horse and followed the wounded man. Overtaking him, he spoke in a voice soft enough for a lady’s parlor:

“There’s good water over there.” The general pointed. “Behind the house. There’s still water in the well. To clean your wound.”

Twelve forty p.m.

South of the Darbytown Road

“Those are legs you got, not candy canes,” Oates snapped. “Y’all keep up.”

Hot as a baker’s oven, all right, and men were going down. But he was determined to trot them and get them into the fight with no time lost. Staff men had dashed by, wetting their drawers and wailing that the Yankees had broken through, that Oates’ 48th Alabama and the 15th, the latter stolen by a human carbuncle, that oozing chancre, Lowther, were the only hope to stay the disaster up on the Darbytown Road.

Oates hadn’t waited for Lowther to cite date of rank and try to take charge of both regiments. He got his boys going at the double-quick. Would’ve whipped them like mouthy coons, if he’d needed to. Wasn’t a day for pity, not one ounce. His bad hip ground so wickedly he could almost hear it creak, bum leg arguing hard against the pace. But this was a day for dirt-fighting, not show-fighting. He’d sent his new horse to the rear, getting down with the men. Oates meant to remind everybody, from Bobby Lee down to the lowest skulker, what a man could bear, what a man could do.

But, damn, if Lowther didn’t follow after, trotting hard and going afoot himself. Oates preferred to think that his old 15th followed after him, though, the way a hound still harked to an old master.

“I’m cooking right up,” a man called, the strain of the day in his voice.

“Well, see you cook right through,” Oates told him, all of them. “I’m hankering for side-meat, you can spare me the fixing up.”

Going through a stretch of trees, he made sure no man slipped off. Every rifle mattered. And there was pride.

Lord, it was a hot one, though. With the gone rains haunting the air.

Battle noise kicking up and closing in. Yankee artillery delighting itself, spendthrift with ammunition.

Oates doubled back along the column, using himself hard, ever seeing to the things that needed seeing to. Another soldier began to stagger. Captain Wiggenton seized the man’s rifle, lugging it for him, and insisted the man keep going.

Young Wiggenton was one fine officer.

Oates sprinted back to the head of his little column, hip a misery.

As soaked as if they’d been tipped in a creek, the lead company left the trees for the light of a field. Just ahead, the Darbytown Road was Lucifer’s own chaos. Men ran every which way, but mostly the wrong way. Oates cast about for anyone who wore enough rank to give him orders, who might know where they were wanted.

It looked as though they were needed everywhere, but the worst of it, a crashing, howling mess, sounded down on the right, a roustabout brawl of thousands. Smoke struggled up through rotten air, chased by the roar of men turned into beasts.

Oates recognized General Anderson. Not in his chain of command, but it hardly mattered. Without giving Lowther time to catch up and assert his seniority—let the man’s cowardice show to the whole world—Oates halted his shred of a r

egiment.

“Oates?” the general said. “Good God, man, you’re welcome here.”

“Got my Fortykins. Fifteenth’s coming up. Where should I take them in?”

Anderson looked doubtful. Maybe reckoning how small a force trailed Oates. Maybe stunned out of good sense.

Oates waited. Impatiently.

With a troubled nod, Anderson told him, “Eighth Georgia’s still holding on. Down there.” The general pointed. “In that piece of woods somewhere.” He smartened his carriage. “Oates, if you think you can do anything … go tearing into them.”

Oates snapped a salute.

The Federal line below, glimpsed over low trees, had regrouped and looked set to parade. Near a mile’s worth of them, stretched across a great field and into a grove. He did believe he saw where he needed to go, just on their flank.

“Alabama! Forward … right oblique … march!” Time to quick-march now. Let them catch a bit of breath, with the fight coming. Keep them together. When they were on their way into the cauldron, he added, “Time to earn your pork and pone, Alabama.”

“Ain’t seen no pork in a Bible age,” a soldier called back.

Another man cackled, “Git me some Yankee bacon.”

“And coffee,” another called.

That deep-down thrill on the verge of a fight was in them now. They’d fall down dead before they’d skulk away.

To Oates’ surprise—mixed pleasure and displeasure—Lowther made the 15th conform to the 48th’s movement, trailing on the left. Lowther … was almost acting like a soldier.

A wide grove, not too deep. Treetops and branches cracked off and crashed down under Yankee artillery. Had to go through it. Get on that flank. Halfway onto it, anyhow. Overlap them.

“Come on, boys, keep your order and come on!”

He called out to his captains and lieutenants, telling them to deploy the regiment into two lines as soon as they left those trees. And to be quick about it.

The noise in the grove was stunning. Whole trees toppled. Men hurled themselves out of the way.

Darkness at Chancellorsville

Darkness at Chancellorsville Shadows of Glory

Shadows of Glory Red Army

Red Army Cain at Gettysburg

Cain at Gettysburg Valley of the Shadow: A Novel

Valley of the Shadow: A Novel Hell or Richmond

Hell or Richmond The Damned of Petersburg

The Damned of Petersburg The War After Armageddon

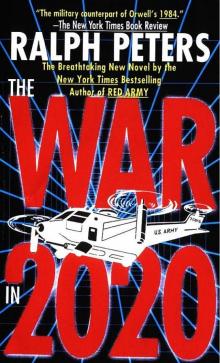

The War After Armageddon The War in 2020

The War in 2020