- Home

- Ralph Peters

Hell or Richmond

Hell or Richmond Read online

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce, or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To the flesh-and-blood men who struggled,

before we turned them into bronze and marble

Contents

Title Page

Copyright Notice

Dedication

Epigraph

Part I: Stars on Their Shoulders, and Stripes on Their Sleeves …

Prologue

Map

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Part II: Wilderness of Blood

Map

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Map

Chapter 8

Map

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Map

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Part III: A New Kind of War

Map

Chapter 13

Map

Chapter 14

Map

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Map

Chapter 18

Map

Chapter 19

Map

Chapter 20

Part IV: Marching to Hell

Map

Chapter 21

Map

Chapter 22

Map

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Map

Chapter 25

Epilogue

Author’s Note

Key Characters

Ralph Peters’ Novels Published by Forge

About the Author

Copyright

Peace is despaired,

For who can think submission? War, then, war …

—JOHN MILTON, Paradise Lost

PART

I

STARS ON THEIR SHOULDERS, AND STRIPES ON THEIR SLEEVES …

PROLOGUE

March 10, 1864

Brandy Station, Virginia

Rain. Thudding on canvas like bullets on flesh. Imagining a different sound, he rose and opened the tent’s flap.

Merely a courier passing by, fighting the mud for mastery of his horse. Not the visitor. Another man might have felt reprieved, but that was not his nature.

Would he be able to hear the train? Or the band when it struck up down by the siding? Would he have a last few minutes to prepare himself?

The rain only dirtied the day, leaving the stripped land as colorless as the uniforms south of the river, the fouled garments of the men he had learned to kill. And to respect.

He coughed.

Letting the sodden flap fall, he turned back to the emptied headquarters tent, a domain of maps and papers, of lingering human scents. The stove reeked of damp wood and ancient ashes. He had ordered the plank floor scrubbed, but the effort was futile. With each tread mud oozed up between the boards.

Determined not to make things worse, he sat down, jarring old bones. But he was not in command of himself this day. He soon got to his feet again, fussing with his uniform as he paced the canvas cage. Was that the rumble of the train from Washington?

The heavy rain obscured all other sounds. He had refused to let Humphreys site the headquarters close to the station, with its smoke and stink and noise. For the first time, he regretted that decision. This wait was abominable.

He wiped his nose with a handkerchief hard used. In the old days, before the madness of the war, he had been particular as to the freshness of his handkerchiefs. Now such matters seemed laughable.

Damnable illness, a vicious living thing in the lungs and throat. He had thought himself quite over it that morning. But the pestiferous cold without would not let go. Nor was it honest Philadelphia cold, but a damp wickedness crawling into the lungs and clawing the sinuses, assassin of consumptives. No wonder more soldiers died in camp than in battle. Even the weather aligned against him now, another enemy.

At least it did not seem to be a return of his pneumonia. The politicians and their favored generals had tried to employ even his health against him, declaring him unfit on that count, too. Yet, he had won battles, and they had not, an achievement that would never be forgiven.

Plagued by nerves and temperament, he opened the flap again. The landscape lay drear and dead, with no hint of spring. The war had passed over it many times, impoverishing its poverty. If the men across the river were fighting for this wretched dirt, he was not. At the start of the war, he had served a noble idea and kindled ambition. Now he fought because it was too late to stop, too ignoble after such a torrent of blood. He still believed in the justice of his cause, in the sanctity of an undivided Union, but the fine words that once had passed his lips were gall. What mattered now was the debt owed his dead and holding fast to his honor. The thought of defeat, of quitting, was unbearable.

But the choice had been taken from him. He knew what was coming on that special train: not just a man, but a sentence.

He made a fist at the air, embarrassing himself. The Committee on the Conduct of the War was a damned disgrace, a cabal of drunkards trafficking in lies. He hated politics, had always hated them. Now he was mired in their filth. There were times, black times, when he wondered if his government merited saving. Scoundrels were permitted—nay, encouraged—to undo the reputations of decent men.

The rain, the rain. Let the spring come and the marching into battle. Even if he would no longer be part of it. Let the sun warm the shoulders pressing forward in blue columns, let someone force this horror to an end. Even if that someone could not be him.

He dropped back into a camp chair, sour and heartbroken, yearning for a chance to show them all, to frustrate his accusers. He believed he was still the man to lead this army. He knew how to fight the men south of the river. But he lacked the skills to defend himself against the press and hireling politicians.

He had to do the honorable thing, he understood that. Today of all days, it was vital to remain a gentleman, to speak faithfully and betray no emotions to his career’s executioner. His family seemed ever destined for disappointment: his father, now him. Yet, he had done much, giving them all the victory they needed, that victory and more.…

Only to have a low cabal poison Lincoln against him. Liars. Devils. Whoremongers. Intimating, in the wake of Mine Run, that he sympathized with the Confederacy, that he was unfit to command, even that he was cowardly. All because he would not squander thousands of men to no purpose. Oh, yes. Had he overruled all military judgment, common sense, and decency and ordered Warren to attack, had he sacrificed five thousand soldiers in an act of folly, he might have been forgiven. But powerful men never spotted near a battlefield had seized upon his refusal to charge Lee’s entrenchments, coiling like snakes to strike his reputation. Their ardor for slaughter repelled him.

Perhaps he was better off being relieved. He could put this filth behind him, this infinite human vice of cold ambition. He could not understand how men could tell a public lie and then stand by it. He was not made for the politics of command, not for politics of any kind. He knew that his notions of honor seemed quaint, even laughable, to the likes of Sickles, Hooker, and Butterfield. But he could not imagine a life liv

ed another way.

It would have been best to remain a corps commander. Or merely the commander of a division. The leadership of this army had brought with it more threats from the rear than from the Confederacy.

He wiped his nose, wet linen on raw skin.

Soon, soon, blessedly soon he would return to Margaret and the children. Taking pride in what he knew he had done and leaving the vultures to feast on the country’s carcass. Damn them all. Let them have their misbegotten war.…

Yet, even as he railed against the world, his heart declared against his going home. He longed to finish what he had begun, then to go back to Philadelphia in triumph, not odium. The unavoidable speeches of praise by aldermen and consolation banquets at the Union League would only prolong the pain. He wanted to stay here and fight. But the choice was not his to make.

Another fit of coughing dragged him back to the front of the tent. He hacked up what phlegm he could and spit into the mud. Still nothing. Only more rain. Preferring to do things properly, he would have liked to post an honor guard at the station. He felt no resentment toward the man himself. But the rain made the prospect of troops on parade a travesty. Only an ass would give soldiers a needless drenching. The war had taken decent men beyond that. He had settled for a few bandsmen and a lean retinue selected from the staff.

A mighty burst of rain assaulted the canvas, conjuring Gettysburg: his hour of glory, of triumph. The smoke, confusion, and carnage had calmed to reveal his army victorious. Lee had been defeated. Lee! His elation on that July afternoon had soared beyond all words, beyond his deathly exhaustion, and he had thought, mistakenly, that all might be well thereafter. Only to spend the night wrapped in an oilcloth, sitting on a rock amid the mud, under a tree that channeled the rain into torrents. Every roof had been required for the wounded his victory cost.

The wounded, in their legions. Damn Washington, and damn the New York papers. None of the men in frock coats and cravats understood the human side of an army. How they had howled—and were howling still—because he had not chased Lee like an ill-trained dog. They refused to hear that three hard days of battle had left tens of thousands of wounded men in his care and thousands more as prisoners on his hands. They did not want to hear that his army, too, had been mauled and thrown into confusion, that officers had been slaughtered by the hundredfold, that ammunition pouches and caissons had been emptied, that entire divisions had nothing to eat and no water untainted by blood, that the corpses of the brave baked in the sun, or simply that he had done the best he could. The Army of the Potomac had worked a miracle, sending Lee home in shame, but it had not been wonder enough for the stay-at-homes.

Now their spite had caught up with him, with an innocent man their instrument, and he would be replaced by Baldy Smith, a rude and cranky fellow. It was humiliating. But he was determined to bear it as a gentleman.

The rain retreated abruptly, leaving a rear guard of droplets. Perhaps the change of command would bring the army better weather. And dry the damnable mud of “Old Virginny.” His men needed to escape the stench of their hovels and the diseases crowding bred. The sick rolls and the tally of the dead were simply appalling. The men needed the warmth of the sun to quicken their muscles and fresh air to lift their hearts.

He sneezed and felt his beard for snot. It was vital to maintain his dignity. His visitor had soared above them all. He remembered the fellow from Texas and then Mexico: sun-reddened and rusty-haired, otherwise nondescript, of medium height and build, earnest and amenable, the sort of lieutenant you called upon to make up a fourth at cards. He always had seemed a lonely man, but they all had been lonely for their wives and sweethearts in those Texican days when the war refused to come. He himself had been a staff engineer, the other man a chafing quartermaster. At Monterrey, they had been thrilled by war, young men eager for accolades and brevets. It was grotesque to remember it now, how even he had viewed war as romantic. And the sad, silver-jangling Mexicans obliged them.

He had not heard the train or any warning fanfare, so the ruckus of horses slopping through the mud close by surprised him. He stood, straightened his uniform, and fixed his hat on his head. Stepping out onto a walkway of planks, he scanned the powder-smoke mist.

His visitor rode ahead of the others, as if he knew exactly where he was going. The man had always had a good seat on a horse, had set some sort of equestrian record at West Point. Or was that someone else? At times he feared his memory would betray him. Forty-eight? Not so old. But old, too. War wanted the young. He cleared his throat and—just then, of all times—the damned fleabites on his calves began to itch.

He might not miss this, after all.

The visitor rode close, dropped easily and carelessly into the muck, and strode toward him. Splashing defiantly, determinedly, as if no mud would dare hold fast his boots. The other horsemen held back, fixed to their saddles.

There was no saluting, no formality. The visitor pulled off a riding glove and extended his hand.

“General Meade,” the man said in an easy western voice. “Sweet weather, ain’t it?”

Meeting the visitor’s cold flesh with his own, Meade replied, “Lieutenant General Grant, sir. Welcome to the Army of the Potomac.”

* * *

“Coffee?” Meade asked, prepared to call for an orderly.

Grant shook his head. “Best get down to business.” His face was set, emotionless, the common jaw outlined by a close-cropped beard.

Meade gestured toward a camp chair. “Please.”

Retaining his plain soldier’s overcoat, Grant sat down. The coat filled the tent with odors of old tobacco and wet wool. It wanted laundering.

Meade remained standing, posture erect, though not to parade-ground extremes. He wished to appear respectful, but not pompous. It was such a damnably awkward situation.

“Sir, if I may?” he began. He had prepared his speech, a schoolboy facing chastisement and hoping to salvage his pride.

Slump-shouldered and inscrutable, the newly made general in chief gave a single nod.

“General Grant … I understand that you may wish to name your own man to command the Army of the Potomac. I should regret that, of course. I should regret it a great deal. But I do not believe that the feelings or ambitions of any officer can be allowed to stand in the way of … of our efforts to end this war. What I mean to say is … I will neither protest nor resist your decision, whatever it may be. There will be no politicking, no underhandedness. We’ve had enough of that.” He breathed deeply, careful not to let it sound like a sigh, and forced himself to conclude. “The Union matters. I don’t. You may count on my … comity. And my full support, sir.”

Grant’s pale eyes remained inhumanly steady, but he gestured toward the chair nearest where he sat. As if he, not Meade, were the host. Suppressing a cough, Meade obeyed. His throat felt raw and his calves itched. He truly did feel old.

The younger man, arbiter of his fate, drew a pair of cigars from his overcoat. He bit off the end of one and extended the other to Meade.

Why not? Meade decided. Damn the old lungs. And damn this weather. Damn all of Virginia.

Grant struck a match and lit his cigar, but let Meade light his own.

Just say it, Meade thought. Finish me off. The way you would a lame cavalry mount.

Grant sat back, puffing. The overcoat bunched around him, as graceless as a blanket. “Jealous of you in Mexico,” he told Meade. “Staff engineer seemed a high and mighty creature. Envied you being in on things with Old Zach.” A smile ghosted by. “Beat you at poker, though.”

Their minds had run close, perhaps inevitably. Mexico was what they had in common. That and West Point. “I was just thinking that you remind me of General Taylor,” Meade said.

Grant brightened. “I take that as a compliment.” The Union’s first lieutenant general shifted in his chair, as if he had his own itches to resist. “Wasn’t just porch talk, Old Zach. Knew how to make men go, how to reach right into them.” Assessing his ci

gar, not Meade, he continued: “Different business now.”

Glad to take refuge in memories, Meade asked, “Do you remember how it struck us when Major Ringgold died? How unbelievable it seemed? These days,” he went on ruefully, “a major general’s death would hardly be noticed.” The cigar Grant had given him was of fine quality. He addressed it with care, determined not to fall into a coughing fit. “One thing I certainly envy General Taylor is the freedom he had. To do what needed to be done. Such liberty seems unimaginable now.” Meade shook his head. “The bane of my command has been modern communications, the damned telegraph. And proximity to Washington. The amount of contradictory direction I receive daily all but paralyzes this army.”

“That so?” Grant asked. His tone had become impersonal again. That voice was not unfriendly, but neither could Meade detect warmth in it.

Never a patient man, he decided to have his say. Grant could choose to listen to him or not.

“General Grant, if you want your commander of the Army of the Potomac to succeed, you must stand between him and Washington, all the damned busybodies. Just let him fight. This is a fine, fine army, a fighting army. I tell you, it’s at the peak of its capabilities: nearly a hundred thousand men, spirited and ready. More, should the Ninth Corps join it. But it cannot be commanded and fought from Washington.”

“Noted,” Grant said.

“And I hope you’ll permit my successor to execute the corps’ reorganization. Oh, I know the arguments against it … too many divisions for one general to control, the unwieldiness. But the damnable thing is that I have only three capable corps commanders to offer my successor. Not four or five. And it’s only three if Hancock’s wound doesn’t invalid him out again. He’ll be back with the army any day, but the surgeons seem to have made a thorough mess of things.”

“Win’s a tough bird,” Grant said. “Other two Warren and Sedgwick?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Warren up to a fight?”

“Yes, sir.”

Grant flipped the stub of his cigar onto the planks and crushed it with a boot heel: a raw man of the West, another breed. His lips suggested a smile, but none appeared. “Fine work at Gettysburg. Been waiting a while to tell you that. Ignore the committee. And the newspapers. Only difference between a reporter and a fifty-cent prostitute is that the latter has to be moderately presentable.”

Darkness at Chancellorsville

Darkness at Chancellorsville Shadows of Glory

Shadows of Glory Red Army

Red Army Cain at Gettysburg

Cain at Gettysburg Valley of the Shadow: A Novel

Valley of the Shadow: A Novel Hell or Richmond

Hell or Richmond The Damned of Petersburg

The Damned of Petersburg The War After Armageddon

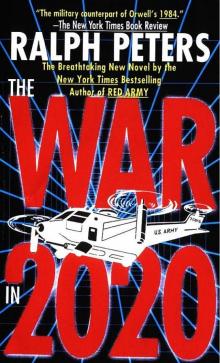

The War After Armageddon The War in 2020

The War in 2020