- Home

- Ralph Peters

Darkness at Chancellorsville

Darkness at Chancellorsville Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Author

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

Tom Doherty Associates ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce, or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To Dr. James S. Pula,

in honor of his pioneering work

on the vital, dramatic, and long-slighted roles

played by immigrants and freedom fighters

from central and eastern Europe

in our Civil War.

And it will come to pass, when some of them be overthrown at the first, that whosoever heareth it will say, There is a slaughter among the people that follow Absalom.

—2 Samuel 17:9

PROLOGUE

Saint Patrick’s Day 1863

Kelly’s Ford, Virginia

Sam Chamberlain fired his Colt at his own men as they retreated, at the Rebs on the far bank who’d turned them back, and at all the worthless world.

“Goddamned cowards.…”

With his face shot through, the words emerged as grunts. Blood chilled and clotted on his jaw, his neck. Doused in icy water, his uniform sheathed him.

The revolver clicked empty. A last cavalryman’s horse gripped the mud of the bank and spattered past, its rider mad-eyed.

Chamberlain spit out another tooth, maybe a splinter of jaw bone. Lowering his pistol in disgust, he watched the river’s current tug his dead horse from the shallows. Determined to save his saddle roll, he entered the water again.

Even the river betrayed him. The carcass fled downstream.

Hatless and drenched, with high boots bucketing water, he coughed out more bloody pulp and cursed again. The wind combed strips of face-meat.

Never was a beauty. Less of one now.

He stared across the river as cold water scoured his groin. Shivers gripped him, uncontrollable, strong.

“Go on home, Yank,” an unseen Johnny called. “You just go on home now.”

Had the ford not been deepened forbiddingly by melt, Chamberlain might have crossed that river on foot and gone at the hidden graybacks with his fists. Find them and flush them out, every last one.

Only saw them when they rose to fire. Behind the slashings. Some in a ditch, others in that brush.

Twice, he’d tried to lead a detachment from the 4th New York to clear the far bank. And twice the men had lost their nerve midstream and turned their horses. Then he’d called up soldiers he’d believed better, lads from the 1st Rhode Island. They, too, had quit, although one had tarried long enough to free him from tangled reins.

Pain swept him. Monstrous pain, delayed then delivered with interest. His face had burst like a pig’s bladder poked with a knife. He could have howled.

But Chamberlain only gummed out more obscenities, wiping blood from an eye with a sodden glove.

Staring across the swirling brown water, he felt frozen inside and out. Unable to move or be moved. Outraged beyond human compass. Helpless.

A hand gripped his upper arm.

A bullet tore past. Then another.

“General says come back right now, for God’s sake.”

* * *

Bill Averell watched his chief of staff stomp through the mud, face so mutilated that Chamberlain was more recognizable for his bad temper than his features. A sergeant tried to drape a blanket over the major’s shoulders, but Chamberlain cast it off with the growl of a beast.

Sorry shit of a morning. Averell had dispatched an advance detachment of a hundred men to secure the ford, and the effort had failed utterly. Now here they were, in the full morning light, his two brigades held up by a handful of Rebs.

Fitz would gloat when he found out. Damn him.

Old Fitz. Fitzhugh Lee. With those ain’t-you-small-now? eyes that put every man in his place. Chums at West Point, neither one a scholar. But friends or not, Fitz always had that knack of reminding you that he was a Lee of Virginia—and not from a lesser branch of that august family. As a cadet, Fitz had been the queerest mix of merriment, mischief, and snobbery that Averell had encountered among the Southerners. And he’d had some competition.

Now he and Fitz ruled opposite banks of the Rappahannock River, but Fitz had crossed over one too many times, ending his last foray by leaving that snot of a note:

Dear Billy,

I wish you would put up your sword, leave my State, and go home. If you won’t go home, return my visit, and bring me a sack of coffee.

Fitz

This day had been chosen for the return call. But his men couldn’t even get across the river. Averell was tempted, again, to call up his rifled battery and blast the Johnnies, but with the bulk of his command still hidden, he didn’t want to reveal his strength to the Rebs: Cavalry alone signaled a patrol, but artillery meant that someone had come to fight.

He did want to teach Fitz a lesson, though. Had to do it. Matter of pride. Not just personal vanity, but the honor of his command, the restoration of the cavalry’s tattered reputation. He’d promised Stoneman and Hooker his men would show well, that he’d raised his newly acquired division to a higher standard. And Hooker had licensed him to show its mettle.

Now this slipped-on-dog-shit start. High water swept heavy limbs downstream and the ford’s approaches were already hoof-cut. Each new assault grew more difficult and slower. The river’s current stole the lives of his wounded, and one blue-jacketed corpse had snagged on a branch, a discouraging display for men going forward.

In sheltered spots across the ford, snow bandaged the earth. Cold air scraped. And two thousand men waited uselessly in the mist.

Not so gently mocking Averell’s upbringing, Fitz had entertained their classmates by dramatizing the differences between a Virginia plantation and an uplands New York farm, drawing everyone in with his patter and mimicry, his cavalier’s velvet disdain. Averell would regret to the end of his days revealing to Fitz that he’d worked in an apothecary shop before getting his appointment to the Academy.

He was about to call up the battery, plan be damned, when Lieutenant Brown nudged his gelding forward, risking a black-tempered blast. Sim Brown was all right, an eager boy. But Averell reserved the right to rip his darling head from his youthful neck.

“General Averell, sir? I can get across, I can do it. I watched, I know where the bed’s good. Let me take volunteers. I can do it, sir.”

Averell snorted. “After Sam Chamberlain couldn’t?”

The lieutenant had spoken his piece and now he waited.

Well, why not? If the lad wanted to hurl himself into eternity—by way of an ice-cold river—wasn’t that war?

“All right, Lieutenant. If you can get those stump-fuck skedaddlers to follow you, give us all a lesson in how it’s done.” Smarting under the day’s embarrassing start, Averell added, “And God help you, if you make a mess of it.”

* * *

Brown led eighteen men toward the river. He’d expected more volunteers, but the boys were spooked: another hard-luck day for the Cavalry Corps. Didn’t see how he could back out, though. After his show of bravado in front of Averell.

Well, Averell was a decent sort, when he wasn’t in a temper. He’d write a pretty letter to his mother. “I regret to inform you that your gallant son…”

Wasn’t quite the way Brown had imagined ending up. Never had bedded a woman. Now he regretted not taking advantage of Washington’s well-drilled whores.

His little party emerged from the skeletal trees and faced the river. Afraid to look back and find himself alone, he left his revolver holstered and drew his sword.

“At the gallop, charge!” he cried. His voice seemed too weak by half. Puny.

His mount defied the mud, though, almost leaping the distance to the water.

Reb rifles blinked from the far bank. Behind Brown, supporting fire crackled, augmented by shouts of encouragement.

His horse struck the river with a clumsy splash. Spray pecked Brown’s face. The water topped his right boot, flooding its depths.

Christ, the water was cold.

Fighting the current, his horse seemed to grow stronger, as if it had become one giant muscle. Half kicking the bottom, half swimming, it shook its head and blew its nostrils open.

Brown believed—hoped—that he heard other riders by him.

Don’t look back. Don’t think. Keep going.

“Come on, boys!” he shouted, voice still little more than a child’s cry. All of him a-shiver. The unbelievable cold of the river. Plus the chill of fear.

Bullets hissed past. The Rebs yelled, crazed. His volunteers responded, the Irish among them bellowing curses and taunts to frighten death. Sudden gasps pierced the uproar.

The far bank seemed impossible to reach, ever receding.

“Come on, we’ve got them!” Brown shouted. A leader, a liar.

Icy water leapt to scorch his lips.

He would not turn back. Damn it. He would not do it.

Waving his useless sword, all but begging the Rebs to empty his saddle, he clung to his horse’s mane with his left hand, a thing forbidden by the riding masters.

Nearby a soldier blasphemed with fury, but the voices were fewer.

His last command.

A sergeant surged past on a huge black horse, racing Brown to the bank. An instant later, blood and meat and bone tore from the man’s shoulder.

That, too, spattered Brown.

Just keep going.…

There were no more words thereafter. Only an animal howl that surprised him as it erupted from his throat. Rage gripped him, vanquishing thought. Now he longed to kill, to take men’s lives.

Spurring his horse, he pointed his saber straight at the far bank, hardly feeling its weight.

“Come on!”

Abruptly, his horse stopped floundering. Hooves bit mud. The animal lifted itself and its burden, mounting that unreachable bank, streaming water. Free of the river, the beast neighed triumphantly.

Astonished to find himself alive, Brown looked back at last. Only three of his volunteers had survived the passage. But they joined him.

And that was all it took. A miracle unfolded. Instead of shooting the riders down, the Rebs leapt from their hides, scooting up the slope by the dozen, quitting.

A cheer went up from the bank Brown had left behind. But there was no time to revel in it. Surely the Rebs would get over their moment of panic.…

Rising in his stirrups, Brown waved his sword, shouting and gesturing: “Come on, come on!”

The morning’s mood had been transfigured, a man felt it like a sharp change in the temperature. Disorganized at first, blue-clad riders sloshed into the river to reinforce him, soon followed by a regiment advancing in column of fours.

Guiding his horse into the underbrush, Brown leaned over the animal’s neck and vomited.

* * *

“Yankees want another thrashing, by God we’ll give it to them.”

Fitz Lee’s rich voice rang above the hoofbeats, a voice that might have belonged to a bigger man. He’d been taken by surprise and didn’t much like it. He’d believed the Yankees would lie low a stretch longer, let the river go down while they licked their wounds.

Stuart had taken word of the crossing well, there was that, at least. No hint of recrimination. On the contrary, Stuart seemed to be enjoying himself, accompanying Lee’s column for the pleasure of it, as jovial as if off to a parlor call. Of course, riding out to trouble Yankees was considerably more pleasant than another day of court-martial duty, which Stuart had only the day before declared to be his bane. Not like Jackson that way. J. E. B. Stuart preferring cajoling men over judging them. Not like Tom Jackson at all.

After a pause, Stuart bantered back, “Even Yankees can’t stay in their burrows forever. Had to come out for some air.” He sniffed the gray morning. “Good a day as any to go visiting.”

“Ain’t that just true,” Tom Owen put in. The colonel’s 3rd Virginia Cavalry followed behind the generals, trailed by the rest of Lee’s Virginia Brigade. “High time they come out.”

With Brandy Station and the railroad behind them, the horsemen made for Kelly’s Ford at a trot, careful of their none-too-well-fed horses. There’d been a lull in the firing from the ford, still miles away, but the pickets at the river had held long enough to get word back to Culpeper—and for Lee to call in his regiments.

Raw weather, though. Still no hint of the Virginia spring. Their mounts steamed and men breathed white. Whenever they passed a farmhouse, wood smoke teased them: Breakfast there had been none.

Nor coffee, a hot dose of which would have been a tonic, after Judge Shackleford’s Saint Patrick’s Eve soiree.

Stuart didn’t imbibe, of course, and had gone off to bed early. Now his excellent spirits were a bit trying.

The road rose slightly, changing the pitch of the hooves to a dry-dirt clap. Spend enough years in the saddle, a man learned all the sounds a hoof could make, harmonized with the landscape and the weather. Out west, men lived or died by the hammering of shod government mounts or the tap of Comanche ponies.

Out west. Lee’s once prized U.S. Army career and his life had almost ended in that vastness, with an arrowhead through his body and the shaft stuck in his guts. Broke off the tip and had them draw out the rest. Screamed just once and wasn’t ashamed of it, either. Damn, if he couldn’t still feel it sometimes, the oddest sensation, the body violated. He’d reckoned he was dying, all of them had. But Lee blood ran strong. Two hundred miles of jostling in a litter across Texas and he survived. To find himself on horseback this brute morning.

The old blue uniform had gotten fair value from him. He’d paid back his West Point schooling in full, indentured to the Second Cavalry.

Billy Averell had bled out there, too, with the Mounted Rifles. New Mexico Territory, with the Navajo stubborn and hard atop their mesas. Billy had been cut up so bad he’d been placed on the invalid rolls. Came back to fight when the war began, God help him.

Fitz Lee did hope Averell commanded the column passing the river. Couldn’t help it, he just delighted in yanking down Billy’s pantaloons. Always had. It wasn’t meanness, exactly. Just the manly, Christian order of things. Poor old Billy, hatched in Nowhere, New York, born to milk cows and mix salts for a quack. No grace to a life like that, no dignity. Wasn’t a wonder the Yankees were heathen jealous of the South, of all things that had grace and showed refinement.

Lee’s long beard lofted. Billy was in for a dogging. Love to take him prisoner, see his face.

Hadn’t seen Billy face-to-face since Carlisle and the Cavalry School.

An eager horseman overtook them.

“Well now,” Stuart hailed the rider, voice pleased with the day, “if it ain’t young Pelham himself.” His smile widened. “I’m gratified that Miss Shackleford released you, I’d begun to fear that Samson had his hair trimmed.”

> Raw-eyed, the major saluted. It had indeed been a late night at the judge’s.

“Just looking to my responsibilities, General.” Pelham’s Alabama drawl lazied a sentence out to nigh on a paragraph.

Stuart raised a hand to the rim of his hat, shielding his eyes against an invisible sun. “I do see Major Pelham. That is a certainty. But I do not see his guns. It was my impression that he commanded and directed my artillery. Of which we may shortly find ourselves in want.…”

“Breathed’s on the way, sir. I came on ahead, didn’t care to miss the pleasantries. In case the Yankees aren’t inclined to stay.”

“They won’t be so inclined,” Fitz Lee told them all.

He was just coming off a bout of the camp trots, nastier turn than usual. Didn’t put a man in the best of moods. If that was Billy Averell out there with his pack of clerks, Billy was going to go home well-instructed.

Wasn’t even proper sport in it, fighting Yankee cavalry. Almost wished they were better horsemen, showed more grit. Just to keep things lively.

A rider appeared on the road ahead, galloping back toward them. Lee spurred his horse to meet him.

The scout looked jaundiced and starved, but his eyes burned. “Beg to report, sirs … Yankees, they’re across, all right. Done crossed, all of them. Best part of a division.”

“They coming on?” Stuart demanded.

“Not to a muchness, can’t really figure ’em that way. But they’re across.”

Stuart smiled. And the smile became a grin. “Halloo the fox, boys!”

Gilded by youth, Pelham hooted. The major had been dubbed “gallant” by no less than Lee’s Uncle Robert. “The Gallant Pelham,” adored by maidens. Leaving Fitz and most everyone but Stuart a tad jealous—if Stuart ever felt jealous of any man, it didn’t show.

Even Jackson liked Pelham. Indulgently so.

And the major was a splendid artilleryman, none could gainsay it. Brave to an excess, the best gun-monkey in the entire army. Despite that Alabama tone falling just short of a gentleman’s.

Darkness at Chancellorsville

Darkness at Chancellorsville Shadows of Glory

Shadows of Glory Red Army

Red Army Cain at Gettysburg

Cain at Gettysburg Valley of the Shadow: A Novel

Valley of the Shadow: A Novel Hell or Richmond

Hell or Richmond The Damned of Petersburg

The Damned of Petersburg The War After Armageddon

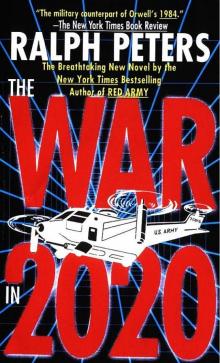

The War After Armageddon The War in 2020

The War in 2020