- Home

- Ralph Peters

The Damned of Petersburg Page 15

The Damned of Petersburg Read online

Page 15

Hogg doubted he had a third of his men still with him.

Confederate guns began to shell the grove. Rounds burst in the treetops, and shrapnel hunted flesh. Limbs and branches dropped on men, breaking bones, and splinters pierced wool and meat. The noise threatened a man’s last grip on sanity.

Hogg scrawled a note: “Have encountered enemy in force. Enfiladed by artillery, both flanks. Unable to advance.”

He chose a sergeant who looked as though he still had a spark of life and told him, “Take this to Colonel Lynch.”

One fifteen p.m.

Bailey’s Creek

“I don’t need to see that coward’s note,” Barlow told Lynch. “I watched his abysmal effort. Hogg’s utterly unfitted to command.”

One thirty p.m.

Strawberry Plains

Grant listened in mild disappointment as Hancock described the day’s actions. Hot even in the shade. Frightful for man and beast. But, in war, a man either drove or was driven. Grant did not mean to be driven.

Grant did note that Hancock’s map was much better than the maps used a month before. The cartographers, at least, were making progress.

Win Hancock stood before him, plump and sweating. The landing and early attacks had not gone well, and Win was embarrassed, eyes as wilted as his starched white collar. The truth of it was, Grant understood, that few of the problems had been of Hancock’s making, though he shouldered them like a soldier. Looking back, Grant saw that the plan had been all clever scheme and no common sense. That river business, especially.

Didn’t do to dwell on it, though. Look forward. Think on what’s next.

“I hear Birney took some guns,” Grant noted. Trying to cheer up Win.

Win nodded. “Heavy howitzers. Rebs couldn’t move them off. Got a flag, too.” In the distance, lazy skirmishers picked and pecked. “Trouble is they’ve had so much time to entrench. Months now. Those lines on New Market Heights have become formidable.”

Grant waved a fly from his cheek. “Plan was to flank the Heights.”

“Barlow couldn’t get up in time. The disembarkation mess. He marched the men as hard as they could be marched.”

“I saw,” Grant said. “Found one in the middle of the road.”

“Day isn’t over,” Hancock tried to assure him. “I expect Barlow to attack in force. Once he’s got everyone up.”

Grant considered Hancock. Best field officer in the East. Or had been. Win couldn’t hide the problem with his leg. Hardly tried to conceal it. And he was growing portly. Man who got fat on campaign wasn’t moving much, wasn’t active. Hancock often traveled in an ambulance, unable to bear the pressure of a saddle.

Many an officer had endured multiple wounds by now. But some wounds healed, and some didn’t. Win would know when his time had come. Unlike Ambrose Burnside.

Two kinds of generals, in Grant’s experience. Those who saw it when they were used up, and those who didn’t. His job was to keep a watch out for the latter.

“Well,” Grant said, prepared to leave, “do what you can today. Hit them again tomorrow. Keep at them, Win.”

Glum faces all around, everyone suffering under the smack-a-man heat, torrid as Vicksburg. But Grant didn’t take as bleak a view of the day as Hancock did. The failed assaults had revealed that Lee had not sent as many forces to Early as feared. Sheridan would be all right out in the Valley. And the presence of Hancock north of the James might even draw back a portion of Early’s command. Meanwhile, Lee would have to stretch again, shifting troops from Petersburg to cover Richmond.

That was a help. Grant was already weighing his next move, another push westward beyond the Petersburg lines. Break up the Weldon Railroad, tighten the noose.

As Grant prepared to leave, Hancock stepped close and said, “Sam, I regret that we didn’t do better today.”

“Lick ’em tomorrow,” Grant told him.

Three p.m.

Petersburg, headquarters of the Army of Northern Virginia

Marshall listened as the generals spoke.

“I fear we must take the risk,” Lee told Beauregard. “I’ll send two of Mahone’s brigades north to Field. He’s facing two Union corps and his flank’s in the air.”

“And if that’s what Grant wants?” the Creole asked. “For us to thin our lines? So he can hit our other flank again?”

Lee’s features revealed more doubt than was his wont. As his military secretary, Marshall had seen far more of the man than Lee revealed to others. That pinched look had been reserved for private hours.

“He may do precisely that. But we must protect Richmond above all, President Davis is adamant.” Lee sighed, another indulgence. “Grant understands that, of course. He’s far from the fool we’d been promised.” Lee clasped his hands behind his back. Though his feet remained planted, he seemed to be pacing in spirit. “It’s one matter to perceive that a thing needs doing, another to enjoy the means to do it. All we can do for now is to parry his thrusts and embarrass his efforts. Bleed him. Shame him. Deny him any victories before November.”

Beauregard resurrected his pleasant smile. “Northern papers profess Lincoln’s a dead man. Politically speaking. Le roi est mort.…”

“Our own newspapers assured us that those people wouldn’t fight.”

Enchanted by any discourse among social equals, Beauregard said, “Those were heady times, we all were foolish then. North or South, I believe we’ve sobered up.”

“Have we?”

Deaf to Lee’s tone—though Marshall was not—Beauregard pressed on. “The North’s weary of this war, just sick to death of it.”

Lee’s expression asked, “And we are not?”

“Look how George McClellan’s rallied the Democrats,” Beauregard continued. “He’ll bring them the Army vote, vraiment. And I know George, he’ll see sense. Once he’s elected, he’ll give a fine speech to Congress and let us go.”

Lee no longer looked at the man who wore the same rank on his collar. But he straightened his back and spirit. In a voice made brisk, Lee said, “Then we must make them wearier still of war.” He turned. “Colonel Marshall? You may draft the order. General Mahone will detach two brigades, but he’s to remain here himself.”

Since the fight over the mine pit, Lee had begun to lean more on Mahone, Marshall had noted. And Lee had made certain that Davis signed his promotion. The old man was forever seeking another Jackson, another worker of wonders.

Well, Mahone was nearly as odd as Stonewall. The one with his cow, the other with his lemons.

“Yes, sir,” Marshall said.

Beauregard exchanged glances with an aide. “And now I must receive a delegation of les femmes héroïques, the sturdy roses of Petersburg.” With a smile, he added, “We’ll see what November brings, cher Général.”

And off he went, all bloody-handed vivacity.

Hours later, alone with Marshall, Lee broke a silence to say, “I fear McClellan will no more defeat Lincoln than he did me.”

Five fifteen p.m.

Bailey’s Creek

Miles got Barlow alone at last.

“Frank, this isn’t working. You’ve been putting men in piecemeal all afternoon. It isn’t like you.”

A walking cadaver with fevered eyes, Barlow said, “The damned problem is that the swine don’t want to fight. We’re left with cowards. The good men are dead.”

Earlier, Barlow had harangued all present about the failure of an attack by the patchwork remains of the Irish Brigade, so reduced that its battered regiments had been folded into Crandell’s Consolidated Brigade, a collection of flags shot to pieces. There had been bad blood on both sides in the past, but it still was a shock to find Barlow gay in his mockery.

A subsequent effort by Broady’s brigade had collapsed under shelling before achieving anything. Now Frank wanted to send in Macy’s brigade farther to the right. Instead of one big push, it had been an afternoon of hapless pokes, with three failed attacks and three brigades broken in turn

. The Barlow of mere weeks before would have cursed the general who made such naïve errors.

And Barlow, of all people, had grown obsessed with securing his flanks, stretching out his frontage instead of concentrating. It was as if Frank had determined to break every rule he’d set for himself.

“Frank,” Miles tried again, “they’re not cowards. They’re used up. They haven’t slept, they’ve had no water. They’re dropping like leaves in a gale.”

“We’ll see what Macy can do.” It was as if Barlow had not heard one word.

Five thirty p.m.

Fussell’s Mill

No mercy to the day. After stumping fiery hot through a litter of sun-felled men and a wasteland of discarded knapsacks, haversacks, bedrolls, rations, playing cards, bayonets, a solitary Bible, and many an abandoned rifle and cartridge box—more like the leavings of a battle than its raw beginning—and after enduring the lung-gripping, break-a-man heat, that air like molten iron, here they were forming up in a let-go field behind a crest that hid the rest of the world and no man could doubt they were going to make an attack, waterless, worn, and witless as they were.

As artillery batteries pestered each other, Private Henry Roback wished himself back in New York. Sitting in the shade, by a deep, cool well.

As parched as their men, the officers limited their orders and exertions to those unavoidable. Colonel Macy rode past, inspecting them, saying nothing. A Massachusetts man himself, Macy got along fine with the New Yorkers and even seemed partial to the 152nd, though not so fond as he was of his own 20th Massachusetts. Macy on a white horse with his left hand lost at Gettysburg and barely back from his last wounding in the Wilderness, a decent man, mostly. Despite all the tribulations of the day, the colonel looked confident, cocksure as a farmer with his crop in. But that was how officers were supposed to look.

Roback doubted that any man present felt good about what was coming.

The brigade just wasn’t the same anymore. Good units had gone bad. The 152nd New York still kept its pride, but all that got them today was a place in the first line.

Gawking rightward, trying to figure things out, Roback spied General Barlow, a demon made flesh, notorious. And just at that moment, a comrade said, “Cripes, there’s goddamned Barlow. What’s he doing here?”

They all knew Barlow on sight. And few wished to know him better. Some said he was a pet of the highest generals, but all Roback’s comrades cared about was that he wasn’t their general, that he led the First Division, not their own. But there he was, over by the sorry rump of the 1st Minnesota, slump-shouldered in the saddle, wearing his calico shirt, and scarecrow-gaunt. And, Roback feared, dispensing commands.

Had something changed? Was he their commander now? No one told them much. And all a man had been able to think about for hours was getting to the end of the march, to water, food, and sleep.

Now there was Barlow.…

A lieutenant called out Company D and led them forward as skirmishers. Roback was glad his company had not been chosen. Wasn’t just that such duty had its dangers. Skirmishing work just took more spunk than Roback felt he had left.

Barlow trotted past, looking queer, with Colonel Macy seeing him along.

Roback knew the signs. They’d advance now.

To where? Couldn’t see past that crest. Could be anything waiting for them. The artillery sure had found something to shoot at. He could spy black dots as shells arced toward the Johnnies, but couldn’t see where they struck. Couldn’t see where the Reb shots landed, either. Heard explosions aplenty, though.

Orders: Attention. Carry … arms. Forward … march.

The regiment’s color guard remained in place and let the front line pass before stepping off. Asking a lot of his horse, Colonel Macy trotted out in front of the brigade. Pointing with his sword.

The heat was worse than a whipping. Damp wool chafed. A thousand strong, the brigade tromped crusted earth and brittle weeds. Heading for that crest.

Waiting officers let the first rank engulf them.

That crest. Blue sky beyond, hard blue, baked. Shells whistled near, but none found them.

Reckon they’ll see us soon as we see them, Roback calculated.

“I’d sell my soul for one schooner of beer,” a soldier panted.

“Devil don’t pay for what he gets for free,” another answered.

The skirmishers disappeared over the ridge.

Roback’s head throbbed. It felt like mighty hands were pressing his skull. He wanted to sit down, to let the other men go on without him this one time.

He longed for water.

They struck the crest and marched over it. Mostly bare, a gentle slope dropped for a quarter mile, a soldier’s nightmare. Patches of no-good cornstalks stood here and there, as if set up by the Rebs to break their ranks, but all the rest was exposed to the watching Johnnies.

At the bottom of the murderous slope, trees lined what must be a stream, if likely a dry one. High on the other side of the little valley, entrenchments and Rebel batteries were visible, connecting one grove to another.

The Confederate guns had stopped firing. Roback knew that the cannoneers were shifting the trails of their guns, repositioning them to fire on the wonderful target the brigade had just presented.

Anticipating the deluge of shot and shell, dry voices ordered men to close up and keep moving.

“Here it comes,” a fellow muttered. No one had the grit left in him to shout.

One after another, four distant guns spit fire through wreaths of smoke. After an infernal wait, the shells dropped on the slope. Two fell short and splashed dirt. A third burst over by the 19th Maine, but Roback couldn’t see the damage done. He had no idea where the fourth shell went, just heard its passing scream and final crump.

Roback had seen the elephant. More times than he cared to remember. The Rebs wouldn’t even adjust the elevation on the guns that had fired short. They’d let the brigade come strolling into range, they had their marks.

Colonel Macy rode out in front again, white horse willing but too worn to prance. Roback had to credit the man, out there holding the reins wrapped around his left forearm, making up for that lost hand, and pointing forward with his sword as if crossing the remainder of the field, getting over that yet-to-be-measured stream, and climbing the hillside to the Reb positions was easy as spending money at the fair.

The next artillery salvo sailed toward them, puffs of smoke birthing little black specks that grew larger as they neared.

More Reb guns opened up.

Whump, whump, whump … whump …

The 19th Maine was getting its share, with Roback’s regiment spared.

Colonel Macy’s horse shrieked and recoiled, front legs lifting, rear legs buckling, blood bursting from its chest. The colonel leapt free as the beast fell, but his arm remained tethered. An aide rode forward, jumped from the saddle, and cut the reins with his sword.

The horse cried out like a soul in deepest Hell.

Then that all lay behind them.

Ahead, the skirmishers quickened. Some went to ground and fired into the tree line’s beard of brambles. Others jogged forward, warily, bent as if resisting a nasty wind. Made small by distance, a soldier flung wide his arms and toppled backward.

A ball ripped through the New Yorkers, tearing a man in two a few yards from Roback. Men in the second rank shouted out, complaining of being drenched with the poor fellow’s blood.

You didn’t think about it. You couldn’t care who it was. You learned to avert your eyes from fallen comrades, to just keep going forward, staring ahead.

Roback felt fainting sick. But he put one foot down, then the other. Keeping his place in the line.

The skirmishers had eased into the woods at the valley’s bottom. Roback just wanted to make it to those trees, setting himself a goal that lay within reason.

Make it to those trees …

They entered a last patch of corn, raising a ruckus.

Rifle

fire zipped over their heads and cut stalks around them. They emerged from the corn and saw tiny flames in the trees off to the flank, where the skirmish line hadn’t reached.

Colonel Macy was back out front, riding a chestnut mount. Roback wished he’d just get out of the way. The men knew Macy, didn’t want to have to learn the ways of another colonel.

A man screamed to high heaven. Unnerving. Few wounded men screamed at first. Too stunned. But this fellow screamed louder than a firehouse band.

Left him behind, too.

Colonel Macy’s horse revolted, staggered, and fell on top of him.

Just keep going. Those woods. Don’t think. Straight into those woods.

The artillery had shifted to the brigade’s second line, Roback could hear the explosions to the rear.

Someone else’s turn.

Just make those trees, those woods.

Bursts of light. Falling men. One fellow shouted church-voiced, calling on Jesus Christ to come and save him.

Officers and sergeants tidied the ranks. Splendidly, the colors remained untouched.

Those woods …

Reb fires. Heavy now. As if the Johnnies had captured repeating rifles.

Order was breaking down. Their lieutenant ordered them forward at the double-quick. Into the woods.

Briars and brush resisted the assault. Men bullied their way through, thorn-bitten, cursing. Roback heard the snap-scrape sound of a bullet striking bone, so different from the thud of a round hitting meat.

Who got it? Don’t think. Keep going.

A voice called, “Help me…”

Keep going.

Heat-groggy, he couldn’t recall if he’d capped his rifle.

The brambles pierced his uniform, tore his hands, clawed at his face. He nearly fell into a rifle pit concealed in the undergrowth. A Reb stared heavenward from its bottom, shot high in the throat. A woman’s straw hat lay beside him, banded with grease.

Darkness at Chancellorsville

Darkness at Chancellorsville Shadows of Glory

Shadows of Glory Red Army

Red Army Cain at Gettysburg

Cain at Gettysburg Valley of the Shadow: A Novel

Valley of the Shadow: A Novel Hell or Richmond

Hell or Richmond The Damned of Petersburg

The Damned of Petersburg The War After Armageddon

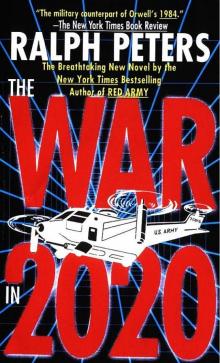

The War After Armageddon The War in 2020

The War in 2020