- Home

- Ralph Peters

Shadows of Glory Page 2

Shadows of Glory Read online

Page 2

“Whiteboys . . .” someone whispered behind me.

The priest had not been quick enough. Before he could shut his hands over the widow’s eyes, she saw what they had made of her husband.

Her scream will never leave me.

The priest clutched her and the babe against him. For just a moment, he shut his own eyes, as if gathering strength. Then he gave it to the lot of them.

“Damned ye’ll be for this. Damned all. Damned.”

Even the hard men made crosses on their chests and lowered their eyes. The women began to blubber, then to wail, and the children cowered behind skirts.

There is foolish, you will say, when I tell you what I did. I looked for the pale young woman with the flame of hair down her forehead. The girl who stood apart.

She was gone.

Her spell broke with her absence, and I turned to duty. The pallbearers had scuttled off to their holes, so I summoned a voice from drill fields past and ordered a few of the Irish lads to help me gather the body back into the coffin.

They were not so much unwilling as afraid. They are a superstitious people, the Irish. I could not get a one of them to move.

The police fellows come up then. They had been but two against the mob and knew better than to go into it. And one of them looked Irish himself. But now they sensed that the danger had passed. We got the body back into its place, though not before I saw enough to haunt me. The corpse still smelled of burned pitch and, queerly, of spent powder. We set the lid on the box again.

Commanding a raisin of a woman to hold the infant, the priest let the widow collapse in the snow and weep while he helped us lug the coffin to the buckboard. He had a workman’s hands.

Twas I who come back first to help the widow to her feet. With the guilt in me. Her wet eyes were as dead as her husband’s body, and she smelled of milk and misery.

We headed for the boneyard, with the police fellows riding behind. The crowd dispersed into the falling snow. The priest would not look at me, or at any man.

I did what I could for the widow. But four years passed before the government could be persuaded to grant her a pension for her husband’s services. By then the child was dead. That, too, was bitter to me. But it does not bear on the tale I have to tell, so let that bide.

“HELL OF A FELLOW, SEWARD. He’s the one should have been president,” Sheriff Underwood told me. He laid aside the bill of fare with the strong hand of a farmer—he had risen from the fields—and gave a tug to one of his mighty ears. “Don’t order the pork. It’s kept over from New Year’s. Lamb’s fresh killed, though.”

He waved to a waiter. The serving fellow was as fancied up as the price of a meal was high. The Benham House was a topper of a hotel, with a piano going in the saloon bar and no spit on the floors. Plush chairs and dark wood set the tone in the dining room. Now there were fine hotels enough in Washington, and I had not come north for my pleasure, but glad I was of the warmth and the softness of my seat. The cemetery had been a cold, bleak spot of earth and my ride on the buckboard merciless.

“Tommy . . . I’ll have that lamb I heard bleating out back,” the sheriff said. The long tails of his mustache willowed as he spoke. “And you tell ’em I want it cooked good and dead.”

“Yes, sir. And the major?” The waiter looked down at me. Twas no surprise he could read a rank. The hotel lobby had been speckled with military men, competing recruiters all, bursting with promises and bounties. Well quartered in Penn Yan’s finest establishment, they seemed to have no regard for the terrible expense and deserved to be brought up on charges. There are always those who will find luxury at the back of a war.

“I will take the stew, if you please,” I told him. There was an awkwardness to my mouth, for I was still thawing.

“One lamb plate, and a bowl of stew. Thank you, gentlemen.”

“Stew?” Sheriff Underwood said as the waiter retreated. The afternoon had mellowed to amber in the dining room, and the tables had lonelied. Many of the guests who had congratulated my host upon his new position were gone already. “Stew won’t keep a fellow going. You’ve got to eat for the weather. Red meat, man. Red meat! That’s the thing. Feed yourself up.”

The sheriff had a prosperous physique. You would have taken him for a politician, rather than a law man.

“I like a good stew,” I said. For such men will not hear of economies. “It is healthful and warming on such a day. Sheriff Underwood, may I—”

“Call me John. And I’ll call you Abel. If I’m able . . .” He laughed and gave one of his remarkable ears another scratch.

“John . . . ” I tried the sound of it. First names do not come so quickly to me, see. I must become a better American that way. I looked at the sheriff, who was an imposing fellow in his very prime. Big, that one. He wore a bright neckcloth, well knotted and trailing, a bottle-green jacket and waistcoat of plaid. All looked of good quality, though a bit roguish by chapel standards. I would have given him the advantage of the fist over a criminal, though not of the chase, for his person did give evidence of a fondness for the table.

Before I could put my question, the sheriff rose to shake hands with yet another well-wisher—for he had been sheriff only since New Year’s Day. A brief conversation ensued between the two of them, so I will take this time to tell you of those ears.

Now, we are not to speak unkindly of another fellow’s peculiarities of person. Nor would I appear basely excitable. But the man had the ears of an elephant. Bristling with hair like a boar. They did not protrude bumpkinlike, but lay flat and fair shielded the side of his head with their length. Twas as if someone had hung red cutlets on the man, such great devices they were. He looked to have ten years advantage of me in the wisdom of age, which placed him square in his forties, and thus time had accustomed him to his awesome companions. But I had a ferocious time keeping my eyes from them. Powerful ears they were, and appropriate, see. For a man of the law must hear things others cannot.

Sitting again, and pleased with the world’s respect, the sheriff told me, “Have to get you up to the farm. Show Washington what a New York welcome means. You can keep all that Secesh hospitality. Won’t be served by no slaves up here. Just the wife and the house-girl.” Smacking the prosperity of his physique with the flat of his hand, he laughed. “Wife’s a devil of a cook. And sometimes she’s just a devil. Don’t I know it? Won’t go near the jail, let alone hear tell of moving into it. Won’t leave that farm even to visit the place. Would be a comedown, of course. Though the county built a nice enough set-up.” His big fingers combed the bristles sprouting from an ear. “Turned it over to my deputy and his wife. Free livings. And aren’t they glad of it? But that one can’t cook to save her life, that Sarah Meeks. Couldn’t very well invite you back there and feed you spittle and grease. So here we are.” He gestured at our handsome surroundings. “Hotel don’t put on a bad spread. Though it can’t compare with good home cooking.”

Now I am fond of my victuals, though I will not have extravagance, but it always seems to me a distraction to conduct business over food. The business is only half attended to, and a fine meal but half appreciated. It is how the better sort will have things done, yet I would as soon have met him at his jail and spared the cost.

“Sheriff Underwood?”

“‘John.’ Got to call me ‘John,’ Abel.”

“Well . . . John . . . I would like to know the details of the finding of our man’s body. I must have the facts, see.”

The sheriff frumped his chin, pulled an ear, and nodded. “Well, we aren’t going to hold anything back from Bill Seward’s personal agent. No, sir. That’s fact number one right there. You’ll have my personal support.” But he sighed. “Don’t you think we should save the grisly side of things for a glass in the club room?”

“I have taken the Pledge, sir.”

A spark of light, perhaps of laughter, lit his eyes. But he mastered his demeanor. “Well, then . . . I guess there’s no purpose in waiting, after all

. Is there?” He deviled his ear again. “Look here, Abel. I want to get this business straightened out as badly as you do. Worse, I expect. I’m the sheriff, for crying in a bucket. Can’t have folks running around like the old Iroquois, scalping and burning and hanging Federal men. Now can I?”

He slumped back, as though the cares of office had already overtaken him. “Bill Remer, now. Used to be sheriff. Gone off to Albany and bigger things. Worst doings he had to face up to was that serving girl drowned her little one in the outhouse last summer. Then that first fellow of yours got himself killed back in November. But Bill Remer knew how to bide his time. Don’t I know it? Just packed up and handed it all on to me. He’s off to the legislature, and it’s all on my head now. And here I’ve got Bill Seward sending his own special agent up to reckon with me, in case I can’t tell a bull from a milk cow. What kind of sheriff is that going to make me look like in front of my voters?”

I almost told him that I was Mr. Lincoln’s agent, not Mr. Seward’s, but that would have been a needless display of pride. And, frankly, Mr. Seward seemed to have more play with the man.

“I have not been sent to chastise or bother,” I declared. “I am prepared to work together, see, and would steal no man’s credit.”

He shook his head slowly. “If only old Thurlow wasn’t off gallivanting in Europe . . .” Then he braced himself up. Stroking back hair and ear with a big hand, he said, “All right, Jones. I mean, Abel. Here’s what I know. And I regret to say it isn’t all that damned much . . .”

A farmer had found our fellow hanging from a tree beside the high road east of the lake. Our man, Reilly, had been recruited from among the local Irish by my predecessor—before his own death—and had not been a felicitous choice. Young Reilly had the curse of the drink upon him and talked grandly in his cups. His boasting of secret entrustments brought him low. His widow said they took him in the night, the masked and silent men who did the deed. She had gone to the priest, not the sheriff, and by the time Father McCorkle went to the authorities with his lean report, Gerald Reilly’s head had been crowned with hot pitch, sprinkled with gunpowder, then set alight. They left him hanging in the winter winds.

“But . . .” I said, “ . . . surely they hanged him first? Before this burning business?”

Sheriff Underwood looked at me with calculating eyes. Gray they were, like the weather. He petted the ends of his mustache where they hung below his chin. Then he reached for an ear. But this time he stopped himself and lowered his hand again.

“I couldn’t say that. And, frankly, I didn’t think to ask Alanson. That’s the coroner. Alanson Potter. Related through the wife, by the way. Farm’s the old Potter place. Grand old family, the Potters. They—” He caught himself drifting and shook his head. “Should have asked, I’ll admit. But I didn’t. Anyway, Potter’s set off to the war himself. Go myself, if I was a younger man. Right thing to do. Essential, if a fellow expects to have a political career afterward. Of course, a sheriff does his part, too. Anyway, Potter’s assistant might know something. We can ask him. Strikes me, though, that it probably went the other way around. With the burning business first. Somebody wanted to lay out a lesson. About the price a fellow has to pay for turning on his kind.”

“But that’s a torment like—”

“Like something out of a damned book of martyrs.” The sheriff wrestled himself into a more comfortable position in his chair. “Don’t I know it? Hardly the sort of thing the voters are going to tolerate in a law-abiding, progressive place like Yates County.”

“At the church this morning—”

He snorted. A last patron, leaving, gave him a look.

“Know what had that crowd all riled?” the sheriff asked.

“Reilly had become known as an informer,” I said. “He was prepared to compromise this matter of an Irish insurrection and—”

“No such thing!” Underwood said. He slapped down a big hand and the table settings jumped. “No such thing, friend. Insurrection, my backside. Couldn’t get those micks out of the saloons long enough to stagger down for a hand-out of free hams. Know what had ’em riled? Somebody spread the word that Gerry Reilly’s job was to put together a list of all able-bodied Irishmen in the county. So they could be rounded up for military service. And they’re terrified of it. Don’t I know it? Frightened as all get out that Old Abe’s going to force them into a blue coat and put a gun in their paws and make ’em fight to free the Negro. That’s what had ’em going this morning, Abel.”

I sat back. For I had believed I had seen the stirrings of rebellion. When all I had seen was fear.

“But these . . . rumors of insurrection?”

The sheriff held up a hand to silence me. An instant later, the waiter appeared at my shoulder. My stew shone thick, and smelled handsomely of beef and pepper.

“You just wait right there, Tommy,” the sheriff told the waiter after the lamb had been laid before him. My host then took up knife and fork and cut deeply into his meat. Twas done to a cinder, and a shame that, for the chop might have made a fine piece of eating. “Now that’s what I like to see,” the sheriff said happily. “A fellow who listens to what he’s told.” He nodded his dismissal to the waiter.

When the man had gone, Underwood leaned toward me. He had spent much of his life out of doors and the history of it was written on his skin. He brought his face so close I could read the veins in his eyes, and the trails of his neckcloth flirted with the gravy on his plate. I could not fathom this gesture of secrecy, for we were now the only diners left in the room. I had been long at the burying and our meal had been much delayed.

“Well, I’ve looked into it,” the sheriff said. “All this Irish insurrection business. Don’t know how the hell the rumor got started in the first place. Not a thing Bill Remer could find, or that I can find. Nor any of the men—deputies, constables or police. Not that the local police are worth much. They’re taking on Irish fellows themselves. But goings-on? I’d hear about it, if anything was happening out in the hills. Farmers know me. I’m one of ’em, for crying in a bucket. They aren’t going to hold anything back for the sake of the Irish—or anybody else. They don’t want trouble coming around to spoil things. War’s trouble enough, with so many of the boys gone. Ploughing and planting’s going to go hard this year. And the drummers now. They hear things, if there’s anything to hear. And they know to pass it on when they do. Likewise, your parsons and such. Even the mechanics and teamsters. The canal people. They all know enough to pass any word of trouble along to the sheriff, whether he’s a new sheriff or old.”

Elbow on the table, he made a great fist. Twas a sign of confidence, not anger. “I know what goes on in this county, Abel. And I haven’t heard one squeak about an insurrection that hasn’t come directly from Washington.” He took time out for a chew and a swallow. “I’ll take you down to the Irish boozers later. Down the way on lower Main. Then we’ll go over to Jackson Street. Used to be all free Negroes back there. Now the Irish are crowding ’em out, and it’s a change for the worse. Let you have yourself a look. And you can tell me if those sorry lumps of rags look ready to break out in armed revolt. Hell, they’re just worrying about getting their next bowl of porridge—or their next drink—and staying out of the county jail.” Speech done, he applied himself to his plate with masculine vigor.

I had been content to listen and eat my stew, for I would have it hot and healthful. Oh, I love to thrust a spoon into the hot, brown joy of a stew and to raise up the treasures the cook has concealed in its depths. But twas my turn to speak.

“Who, then, killed Reilly?”

The sheriff dropped his fork on the plate. It made a great clanking and spatter. “Criminals. Murderers.” He grunted. “Don’t you worry. I’ll find ’em. You can be sure of that.”

We both went at our eating for a bit, and lovely my stew was, though pricey and not to the standards of Mrs. Schutzengel, to say nothing of my Mary Myfanwy, or the wife of Hughes the Trains, or other famous cook

s of my experience. Although I am told it is considered improper by some, I took a swipe of bread to the gravy leavings in my bowl, for waste is a sin. The sheriff did not seem to mind my habits, and I must tell you the fellow had failings of his own. All in all, I found these New York country folk a practical sort, and much to my liking. But let that bide.

“Have you ever,” I asked, in my warmth and satisfaction, “heard anything of ‘whiteboys’?”

I could see by his face he had not. He raised a lamb bone to his mouth, but paused long enough to say, “Never heard of such a thing.”

Neither had I. Perhaps, I thought, I had misheard the voice in the mob. I let it go. For now I had a delicate subject to raise. But I would have an answer, for the truth of it is that I was cross. It had seemed to me a great oversight that only two timid police fellows had been present at the church that morning. And now that I realized Underwood had possessed reasons to fear trouble—based upon those rumors of draft lists and the hatred thus engendered—I was disturbed that he had not stood before the church himself, with the full weight of badge and law.

“I was surprised, John,” I said, “that only two law officers were at St. Michael’s this morning. There was a fuss.”

He wiped his mouth, then his fingers, with his table linen. Rather than showing anger or resentment at my observation, he gave me a little smile of the sort gentlemen exchange in private.

“And you’re sitting there wondering . . . if I know so damned much about what’s going on . . . why the hell wasn’t I out there with the militia called up and standing in ranks?” He nodded at the thought, amused, and squeezed the vast lobe of an ear. “Abel, my friend . . . did you and Bill Seward have a sit-down before he sent you up here? You two have a good talk?” He held out a leather case. “Cigar?”

Darkness at Chancellorsville

Darkness at Chancellorsville Shadows of Glory

Shadows of Glory Red Army

Red Army Cain at Gettysburg

Cain at Gettysburg Valley of the Shadow: A Novel

Valley of the Shadow: A Novel Hell or Richmond

Hell or Richmond The Damned of Petersburg

The Damned of Petersburg The War After Armageddon

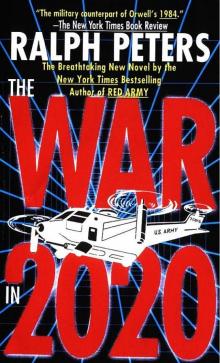

The War After Armageddon The War in 2020

The War in 2020