- Home

- Ralph Peters

The Damned of Petersburg Page 22

The Damned of Petersburg Read online

Page 22

Itching to continue their attack, the Rebs looked to their sergeant. He paused to ask, “Where’s your flags? You’re a general. I want your damned flags, Yank.”

“If you can find them, take them.” He’d left them behind. They only hampered movement in the undergrowth.

“I’ll do just that,” the Reb assured him. “Come on, boys.”

Larking children, they strode on with a yip.

“You git on now,” the guard told Crawford and his officers. The Johnny lowered his rifle to his waist, pointing it at one belly, then another. A long, drenched beard flirted with the rifle’s cocked hammer. “Git along.”

In hardly a minute, they came upon a larger party of prisoners in blue.

“Y’all just go with them now,” their captor told them, eager to rejoin his comrades.

The man had barely turned his back when Crawford ducked into the brush. He expected to hear commands to halt, followed by shots. But the Johnnies had more prisoners than they could oversee.

Crawford set off to rally his ruined division.

Four thirty p.m.

Globe Tavern field

“Those can’t be Rebs,” Charlie Wainwright said. “They can’t be.”

But there they were, emerging from the woods in ragged lines, red flags hanging heavily in the rain.

“Shall I fire on them, sir?” the battery commander asked.

Along the line of guns, other officers and men stared in Wainwright’s direction.

“Wait.”

“They’re within six hundred yards, sir.”

“I can read the range, damn you. Wait.”

Several hundred, at least. More and more. Unmistakably Johnnies. Uncoiling from the woods like a big gray snake. But Crawford hadn’t withdrawn. How had they gotten past him? If he fired on the Rebs, were Crawford’s troops still in the trees behind them?

He remembered Warren saying something about forward troops withdrawing by the flank. Had Crawford pulled off to the left? To uncover his guns?

Where had the Rebs come from? Where was Crawford? Where was buggering Warren?

Four thirty p.m.

Globe Tavern

“Fucked for beans,” Charlie Griffin growled as he rode for the nearest artillery stand facing east. He all but jumped his horse over the gun line.

Pulling up amid the 9th Massachusetts Battery, he shouted, “Don’t you see those Rebs? For God’s sake, fire! Fire on them. Shell, case, solid shot, anything.” The former artilleryman added, “Ricochet your shots in, blast those Rebs to wet shit.”

“I have no orders from Colonel Wainwright, sir,” the lieutenant told him.

Griffin fought down the impulse to thrash the boy.

“I’m giving you the order. And I outrank goddamned Wainwright. Fire on them. Now. Or I’ll take over this battery myself.”

The lieutenant made what Griffin judged to be a wise decision and began shouting orders for his one and two guns to load solid shot, with three and four ramming in canister. The redlegs jumped to the business.

What the devil was Wainwright waiting for? Griffin wondered. Made no sense, with the Rebs coming straight for his gun line, as perfect a target as any in the war. It just wasn’t like him.

Griffin was riding hard for Wainwright, horse battling the mud, when he saw the corps artillery chief raise his arm and drop it.

A dozen guns tore apart the Rebel line.

Four forty p.m.

Globe Tavern clearing

Colquitt shouted orders, struggling to be heard above the clamor of Yankee artillery. Those guns had been positioned perfectly to receive him, as if the Federals had known just where he’d appear. And it was damnably clear that he wasn’t going to get to the tavern, let alone over the rail line, by going it here in the open.

Damned shame, too. They’d made it into the Yankee rear, all right. Except for those guns, all before him was confusion.

But that gun line was too much.

He bullied the exposed flank of his brigade hard to the right, back into the trees, where there seemed to be plenty more Yankees set to surrender.

Four forty p.m.

Globe Tavern, south field, Ninth Corps reserve position

Men cheered as the gun line broke up the Reb attack and drove the Johnnies back into the trees. Brown didn’t holler along, but he did feel the satisfaction of seeing the Rebs take a licking for once.

“Think we’ll go in?” a new man asked, the inevitable question.

“Naw,” Sergeant Eckert told him. “They just marched us out here to serve us that mackerel.”

They’d go in all right. The 50th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers, the rest of the brigade, and, Brown was sure, the remainder of the division. Whatever was going on wasn’t going well. Those Rebs who’d popped out of the trees up across the field might have been repulsed, but there weren’t supposed to be any Rebs there at all. Some high-up general had a hole in his boat.

Anticipating orders, Captain Brumm trimmed the regiment for a fight. Brown got his men in formation, two short lines. Company C had forty-seven men present for duty, including himself. They’d marched with rifles loaded at dawn, and the day had been long and wet. He ordered the men to cap their weapons and aim high into the air, in the general direction of those Rebs.

“Get that barrel higher, Tyson. Shoot up at those clouds.” Then Brown called, “Fire.”

Of the forty-six rifles, perhaps a half dozen banged off.

The veterans understood what they were doing and reached for fresh percussion caps. The newer men looked befuddled.

“Cap your rifles again. Fire as soon as you’re ready. Just make sure you’re aiming high, pretend you’re shooting pheasants that got a good start.”

A few more rifles reported

“Again,” Brown said. “Keep capping and firing. Sparks dry your powder. Once you’ve fired, don’t reload till I tell you to.”

“Look out, boys,” Levi Eckert announced. “Lieutenant’s in a rip-up mood, ain’t had a letter all week.”

That wasn’t true. He’d had a letter from Frances the day before. But the men laughed, easing things, and Brown let it go. Since sewing on his stripes, Levi had shown an uncanny knack for keeping men in the right temper, tamping down fear with laughter. War changed men in unexpected ways, either brought out their best or their worst.

Captain Brumm hurried the regiment through the rifle-clearing trick. A supply sergeant made the rounds with extra caps. Every soldier tried to read the sounds of the battle up beyond the gun line, off in those woods.

The division’s drummers began to beat the long roll.

Four forty p.m.

Coulter’s brigade, Colonel Charles

Wheelock commanding

What was Crawford thinking? The order was madness. To execute it would show his flank to the Rebs while he was moving. They’d roll him up. And now he had artillery pounding his men from in front and behind.

Fuming, Wheelock crouched along the line, followed by his meager staff and ignoring the questioning faces of soldiers huddled in mud-soup entrenchments. With an oh-damn-it shock, it struck him that his 97th New York, on his left flank, had probably already gotten Crawford’s order. They’d be gobbled up if they moved back on their own.

He grabbed a trusted courier by the arm. “Get over to the Ninety-seventh. Quick, man. Tell any officer you find that General Crawford’s order doesn’t stand. They’re to hold their ground, prepared to fight in either direction. Until I send them orders. You understand?”

“Yes, sir.”

The courier, a corporal, was a trusted, skillful man. Wheelock suspected he’d never see him again.

“Well, go!”

The corporal took off through the rain and murk.

More shelling. Heavier from the rear than from the north, where the Reb guns sat. Was Wainwright trying to kill them all? A chill thought struck him: Had the Rebs seized Wainwright’s guns? He couldn’t see anything much, and the tumult and clamor in the

woods gave little away. More Rebel yells than Yankee voices, though.

A shell burst in nearby treetops. Branches crashed down, men screamed. Rifle shots zipped from what should have been the rear.

Wheelock strode along his entrenchments now, shouting orders for his men to climb over the berms fronting their ditches and shelter on the far side. His own corps’ artillery was a greater threat than any Confederate gunnery from the north. And the worrisome Rebs were behind him, not in front.

Mud-slopped and nervous, the men cursed every officer who’d ever lived. But they obeyed him.

Just in time. A line of Rebs crashed through the woods toward them. Wheelock’s regimental officers got their men up behind the earthen parapet and unleashed a volley. Startled, the Rebs halted. Some fired back. For all the racket, Wheelock couldn’t make out what the gray-clad officers were shouting, but after another exchange of volleys the Johnnies drifted back into the trees.

In the wake of the Rebs, the courier dashed back toward the line, calling on his comrades not to shoot. The man was badly shaken.

“They’re gone, sir. The Ninety-seventh’s gone. Nothing out there but Rebs. And prisoners. They’re herding them like cattle.”

The Johnnies had pulled off another of their surprises. It just seemed that the generals never learned. Now the brigade—what remained of it—was cut off. Wheelock wanted to fight, to lash out, but he didn’t like the odds or know which line of attack would serve a purpose. He’d lost one regiment thanks to that fool order, and he didn’t intend to throw away the others.

With the battle sounds rolling westward, he decided to wait a few minutes more, then move out to the south to rejoin the corps. If it still existed.

Five p.m.

Globe Tavern, north field

Warren halted his party among strung-up, half-butchered beeves intended for dinner. The carcasses weren’t what stopped him, though. Just ahead, Colonel Lyle emerged from the wood, unhorsed, hatless, and leading not his brigade, but a dozen men.

“Good God, man, where’s your brigade?” Warren asked.

The colonel looked to the side. He opened his mouth to speak, but language defied him.

Warren felt sick. But he often shivered early in a fight, he knew the pattern. Just had to master himself.

He’d already ordered Griffin to send up two brigades to buttress the line. But that wouldn’t be enough, he saw it now. Soldiers stumbled out of the trees by the hundreds, defeated, disarmed, and demoralized.

But if the Rebs had done significant damage, they had to be breaking up themselves by now. No advancing lines could hold together in that undergrowth. It was time to hit back, to deliver a counterblow.

He’d have to trust to the Ninth Corps. Parke, Burnside’s replacement, hadn’t reached the field, but Warren judged it might be for the best. He’d enjoy unity of command, no hesitation or quarrels.

God only knew if those fellows would fight or bolt, though. Burnside had been shooed away, but his spirit lingered.

At least Meade hadn’t saddled him with Ferrero’s Colored Troops. Either he or Humphreys had shown the sense to leave them behind to man the fortifications.

He waved up Wash Roebling.

“Ride back to General Willcox. Tell him to advance his division immediately. His lead brigade’s to restore Crawford’s line on the right, the second supports Ayres. I want the Rebs cleared out of those trees, and I’ll tolerate no excuses.”

Five fifteen p.m.

The Cauldron

Corporal Will Tanner had been captured, escaped, and been recaptured. But he did not want to test Reb hospitality, nor did he have a desire to see Andersonville, so when one of his fellow prisoners shouted, “Hell, boys, we got them outnumbered, don’t be sheep,” Tanner was one of the hundred or more captives who surged around their handful of guards.

It had almost become a game. The North Carolina boys did their reckoning fast enough and surrendered their arms. Another Yankee grabbed their flag, which the attacking Rebs had left behind.

“We’s let you Yankees go,” a gap-toothed Johnny tried, “so y’all ought to let us’n go on our way, too.”

“Ain’t the way it works, Johnny,” a blue-coated sergeant told the man.

But somebody shouted, “More Rebs coming,” and everybody, in blue or gray, scattered in the direction he thought best.

Five twenty p.m.

Coulter’s brigade, Wheelock commanding

With artillery still blasting the grove from the front and rear, Wheelock made what he deemed to be the best of the bad decisions open to him: He ordered his diminished brigade back toward Globe Tavern. He’d hammered into the regimental officers to keep their ranks tight, maintain close contact, and be ready to fight their way out, but the brush made preserving order a slow business. All the while, treetop bursts added deadly shards to the steady rain.

The battle had moved west, about to the rail line by the sound of it. Might be action to the northwest, too, he couldn’t be sure. And there still were minor exchanges to the east, at the skirmish level. But Wheelock found himself in a netherland, where stray graybacks and Federals alike wandered through the gloom, wounded, skulking, or lost. His men gathered up fifty or so bewildered Confederates, while freeing as many captives wearing blue—including men from his 97th New York. Twice, clusters of Rebs fired on Wheelock’s lines, then disappeared. Discarded weapons lay everywhere, but Wheelock saw fewer corpses or wounded men than most fights produced. Things had gone too quickly to leave many casualties.

When he and his men broke from the trees into the Globe Tavern clearing, with wet flags waving to get everybody’s attention, the artillery finally stopped firing in their direction.

Five thirty p.m.

Risdon house, Confederate second echelon

Mahone was pleased enough by the river of prisoners flowing past, but Colquitt had sent back so many that they interfered with Weisiger’s Virginians as they unfolded into battle lines. And before he went down with a wound, Clingman had sent back word that he was herding at least a thousand Yankee captives northward toward Heth. The attack had certainly bagged its share of blue-bellies.

It was evident, though, that command had broken down out in the trees, that success had brought a threat of disintegration. He’d lost communication with Clingman’s command, and Colquitt had veered to the right after hitting artillery. So Colquitt hadn’t taken the tavern field, hadn’t made it deep into their rear. Nor was there any word from Harry Heth about his advance down the rail line, even though Mahone had sent a succession of couriers back to Hill. He had no idea whether the other half of the day’s attack was succeeding or had fizzled.

And his belly burned like hellfire. He would’ve swapped a hundred Yankee prisoners for one glass of milk.

Plenty of fussing out there in those woods, the units mixed up and fighting all but blind. Reminded him of the Wilderness. Battle was ever attended by confusion, but there seemed to be an excess of it today. And the man who mastered the chaos best would win.

The Virginia regiments dressed their ranks under probing artillery fire, the Federals hunting an enemy they sensed but couldn’t see. Trees concealed them from the Yankees and hid the Yankees from them, all playing a deadly game of blindman’s bluff.

Weisiger splashed up. His horse had finally reached him.

“Orders, sir?” he asked Mahone.

“Colquitt didn’t reach the tavern. Go and take it, Davey.”

Five thirty p.m.

Globe Tavern, north field

Brown marched at the right of his company, ensuring the men didn’t surge ahead of the colors. Rare was the Ninth Corps soldier who wasn’t out for revenge, after the disaster at the Crater. The rest of the army looked on the corps as skunks, and Brown had even heard that Colonel Pleasants, who’d constructed the mine and did his part just fine, had gone a bit mad. So many a fellow had much to prove, and even Brown, a sober man, felt murderous.

On they plodded, slapped by rain, passi

ng the arc of guns. Gone forward on the right, Hartranft’s brigade had engaged the Rebs in a cornfield that edged the clearing, but the long line in which the 50th advanced had three hundred yards to cover to reach the trees. Then they’d see what came of things.

The company split to avoid an overturned wagon, one of its horses dead, the other quivering. Then they closed ranks again, rifles loaded with their driest cartridges and bayonets fixed.

Hartranft’s boys had gotten themselves into a proper fracas. Brown had no doubt that his own brigade’s turn was coming.

Captain Brumm pointed toward the trees with his sword, correcting the direction of the colors.

Dark, wet trees. Not tall, but smoked and ugly. Stray soldiers in blue stumbled out of the gloom.

“Steady up,” Brown snapped. Emulating Brumm, he extended his sword. As if the men didn’t know where they were going.

The sword still seemed a laughable thing to Brown. Not worth much in a brawl, that was dead certain. He wasn’t some gentleman sword-fighter. And his pistol had been stolen the day before, while he was attending to private matters.

He missed the weight of a rifle in his hands.

When the front rank was less than two hundred yards from the trees, Rebs blundered out in a mob. The Johnnies hurried to sort themselves into a firing line, but this time Brown’s side was quicker. Anticipating commands by seconds, the men halted, raised their rifles, and cocked the hammers.

“Fire.”

A heap of Johnnies went down. But they got off a ragged volley of their own as Brown’s men and a thousand others reloaded. The second Union volley sent the Rebs back into the trees at a scurry.

Good Yankee hurrahs trailed after the Johnnies.

Before Brown and his men could resume their advance, an officer in a rain cape galloped along the front of the line. Everything stopped, which made Brown seethe: The Rebs were running, it was plain Dutch stupid not to go after them while they had them spooked.

Instead, the entire brigade left-faced and marched west a hundred yards toward the rail bed. Then they right-faced back into battle lines. The order rang out to advance again.

Darkness at Chancellorsville

Darkness at Chancellorsville Shadows of Glory

Shadows of Glory Red Army

Red Army Cain at Gettysburg

Cain at Gettysburg Valley of the Shadow: A Novel

Valley of the Shadow: A Novel Hell or Richmond

Hell or Richmond The Damned of Petersburg

The Damned of Petersburg The War After Armageddon

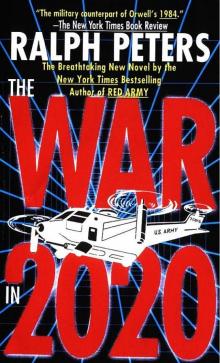

The War After Armageddon The War in 2020

The War in 2020