- Home

- Ralph Peters

Darkness at Chancellorsville Page 3

Darkness at Chancellorsville Read online

Page 3

A Union gun fired a last round and fell silent.

Colonel Alfred Napoléon Alexander Duffié, late of the 4th Chasseurs d’Afrique, re-formed his men for a second time and waited for new orders.

* * *

Averell rode up, trailed by his retinue, and he was livid.

“Christ in a corncrib, Duffié, I told you to hold your position!”

The Frenchman shrugged. “It seemed an opportunity, mon Général.” He gestured at the dead and wounded, at his men who had taken this ground from the Rebels and held it. “It was not badly done, I think.”

“This isn’t a cathouse, damn it, you don’t get to choose. You will adhere—strictly—to my plan from this moment on.” He grunted. “Don’t they teach you to obey orders in France?” Another grunt. “Colonel, you won’t wipe your nose without an order from me. Or you will be relieved of your command. Do you understand me?”

Their horses pawed, impatient of human quarrels.

Again, Duffié shrugged. “I do my best. If this does not suffice…”

Exasperated, Averell searched the faces of the gathered officers—none of them eager to approach much closer. “You, Reno,” he called out to the captain commanding the Regulars, “explain military discipline to the Count of Monte Cristo, would you?”

Without waiting for an acknowledgment from the captain, Averell turned back to Duffié. “Hold this position until McIntosh moves up. When his men come on line with yours, you can go forward. Advance at a walk, and don’t halt until ordered. Then don’t move another step until further ordered. Understand?”

In the distance, from the direction of Brandy Station, a locomotive shrieked.

“Hear that?” Averell demanded. “That could be their reinforcements.”

The colonel shook his head. Mildly. “But this is an old trick, General. Always with the trains, the commotion, to make us believe they are stronger. If they bring more men, I think, the train does not make such a noise to warn us.”

Aflame in the cold, Averell told him, “It may be some damned trick, or it may not. But I’m the one who decides which chances this division takes. And this command will move and fight with discipline. Understand?”

Duffié offered an indulgent, impeccable smile: There was always another army, another war, another adventure—although he quite liked the United States, where even a count’s youngest son was regarded by society as an archduke. In France, he could not have married such great wealth—and the girl was handsome.

“All this is clear,” he told his commanding officer. “Now it is most clear. Je comprends.” He reached out toward Averell, as if about to pat him on the wrist. “I regret that I have made you unhappy, cher Général. But I think that the Rebels are more unhappy, non?”

* * *

Fitz Lee was unhappy. Damnably so. And furious. Seething. Bowels clenched as tightly as his jaw. His mount seemed to cower under him, reading his mood.

On top of it all, he’d lost his left glove. Wouldn’t say a word about it, but the raw cold bit.

His gloves had been a Christmas gift from the best woman on earth.

Around him, his men withdrew sullenly, awaiting the command to halt and fight. They’d had to leave their wounded behind, a rare occurrence.

Only Stuart bothered to feign high spirits. “Reckon we leapt before we looked,” he announced. Banishing thoughts of Pelham, he even grinned. “Learned ourselves a lesson, I’d call that useful. Do better this afternoon. Teach the Yankees something they can show Mammy.…” In a voice redolent of banjos, Stuart added, “Anybody can stand behind a stone wall. Let them come on out and they’ll get their licking.”

Mistrustful of his likely tone, Lee did not reply. But he thought: Wasn’t the damned wall. Fool business to go right at it, that was true, but that wasn’t where the trousers pinched. No, it was that charge the Yankees made. And the ease with which they had repelled his countercharge. No blue-bellied outfit had ever performed like that, not on horseback in an open fight.…

He knew the rule that it took two years to mature a cavalryman. Now the Yankees had had almost two years.

He shook himself, intent on shedding the twinge of alarm. One charge didn’t portend much, after all. Just a hard-luck morning. He ordered himself to believe it, as the ghost of that last bout of camp trots plagued his innards.

Stuart tried again to lift his spirits. “Fitz, you look like you’ve been run out of the kitchen without your cornbread. Myself, I blame those carbines. Downright unfair. Have to capture us more of them, even things up.” He chuckled. Falsely, falsely.

Neither man spoke of Pelham. His loss was too near, too dispiriting. Sorrowing had to be set aside as long as there was fighting to be done.

And there was going to be more fighting.

Lee spoke at last: “I’m going to drive them. By God, I’m going to drive them.”

“That’s the spirit, that’s my Fitz. How’s that next stand of trees look, fix ourselves there? Get a little elevation and clear lines of sight, give our own guns a chance.” Stuart licked flaking lips. “Excellent ground for maneuver, to my eye.”

Lee regarded the line of bare trees, the snow left in the lees. Then he scanned the open ground with a killer’s eyes.

“I’m going to cover that field with Yankee bodies,” he promised Stuart.

* * *

Marcus Reno would have been a colonel, had he made the jump to the Volunteers, but he loved the Regular Army and he was stubborn. He’d loved the Army’s traditions since West Point, where he’d done worse than some and better than others. Now he cherished the gunmetal mornings, the savage bite of coffee cooked in haste, and the waking light. It had always been thus, the delights carved out of misery. His memories were scented with campfires curling smoke in the Washington Territory, and with temptations to which he had sometimes succumbed: No man who had passed through for a single night forgot San Francisco, its raw whores, murderous drams, and voracious bedbugs. His garrison had been elsewhere, though, in the godforsaken scants of Walla Walla, and the duty of the 1st Dragoons had consisted of fruitless pursuits through boundless timber. Now all that seemed a lifetime away, although it was hardly two years, since men now divided had shared their bottles and sins.

What a different, innocent world it had been, their debauchery that of children, their ambitions petty. He recalled his pride in minor commendations, in a major’s stingy praise for a brevet lieutenant on payday parade at a forlorn post the paymaster finally remembered, the impoverished spectacle watched by broken Indians unable to comprehend the white man’s rituals. Nearly two years into this war, Reno remained astonished that a soldier could lose a blanket or even his rifle and not face a board of inquiry. On the frontier, lieutenants had feared the quartermaster’s logs and signature chits far more than they feared Indians. This lurch from parsimony to abundance had been a greater shock than the general slaughter.

The Army was his life, it never wavered. Even this war was but another interlude, and his Regular captaincy would count for something out on the Plains, where the Army’s postwar rump would surely find itself.

No, he would not join the Volunteers, for whom service was an onerous necessity. He felt himself at his best flanked by old sergeants, sour-mouthed fellows who cherished their trade, old before their time and scarred by service, cored by every disease from the pits of vice, men who kept their weapons flawlessly clean, even if water rarely met their bodies. The bugle sounding reveille was Gabriel’s call to Reno, and he ate poor food with zest. The Army was a calling that could not be reasoned out, but duty rewarded those of sturdy faith. A Regular captain, he commanded two regiments this day—the 5th U.S. and his old 1st Dragoons, rechristened the 1st U.S. Cavalry—and he led them with a firm hand and masked affection.

So when Averell, after a slow advance that gnawed the afternoon, ordered them all to halt and extend a division line facing the enemy, Reno took his position on the flank without reservation, curling the 5th U.S. to master the

ground. But the next order, shouted by a puffed-up aide, was surprising and rigid: When the Rebs attacked—which they certainly would, and vengefully—each cavalryman was to steady his mount and hold his ground, not one step forward or backward, and greet the Johnnies with a volley from massed carbines at one hundred yards. After that, every man would fire as rapidly as possible. There would be no retreat, but no charges, either.

Reno shrugged, conditioned to obedience. He’d taken his share of orders he didn’t like, and that, too, was the Army. Averell was just ill-tempered today and far more cautious than usual, but independent command sat heavy on some. And if Averell was no genius, he was no fool. He’d keep them out of trouble. Still, Reno would have liked to combine Averell’s approach with a dab of Duffié’s dash. The Frenchman would have been a caution in the peacetime Army, but he shone on the battlefield. If only you could take the best of both.…

Reno passed on the order: Steady your mounts, rely on your carbines, and don’t move an inch until ordered. His first sergeants, all whiskers, broken teeth, and rotten loins, snorted their distaste but saluted smartly. One merely observed, “Ain’t we got horses beneath us to move us handsome, Captain, sir?”

“No mouth from you, Brady. And remind your men to aim at the chests of the horses. They just might hit something.”

* * *

“Well, there seems to be a lot of them,” Stuart observed. “Out in the open now, though.”

“Line’s long,” Lee allowed. “But only one deep. Hit their center hard, punch right through.” He closed his fist around the tip of his beard, a nervous habit. “Then it’ll be a race back to the ford. Which they will lose.”

“Surely,” Stuart said. After a pause, he added, “I recommend you put everyone in this time.” Lee noticed that his commander’s lips were cracked to bleeding. It had been a long winter and didn’t want to quit. “Only a recommendation, of course.”

Miles to their rear, the locomotive shrilled again, announcing another arrival of nothing at all. Lee did wish he had another brigade. For the surety of it. But he’d made do before, with less. And his boys had their dander up now, gone surly and hard.

He intended to do it properly this time, though. Let Jim Breathed show the Yankees how to handle a battery. Deploy skirmishers in good order. Then he would, indeed, put everyone in.

* * *

Reno couldn’t figure it. The Reb horse artillery was always aggressive, but rarely reckless to the point of folly. Now their lone battery begged for destruction, without any good effect, and Reno could not understand it.

The Reb guns had been driven out of successive positions, outranged and outshot by their Union counterparts. They seemed to have a problem with bad ammunition, too: Many Confederate shells just plowed up dirt. The impacts barely made horses shy.

The duel dragged on, though, through peak afternoon, as the two small hosts held their ground a half mile apart, bound to their saddles, each waiting on the other.

Were the Johnnies scared? That was unlikely.

The advantage in numbers did tilt blue, though. That much seemed clear enough.

Were they prodding Averell to attack them? Did they have a surprise waiting, some hidden reserve? That didn’t feel right, either. With more men, the Johnnies would have attacked already. And made it stick.

The Rebs were masterful bluffers, of course: They played fine battlefield poker. And Reno’s instinct said they were bluffing now. Had he been in command, he would have ordered a general attack.

Duffié was itchy, too, it was so obvious it was almost laughable. Kepi atilt and mustaches perfect despite his early saber-work, he trotted up to “inspect the flank,” but, really, for a chat. The French were supposed to be devious, but the colonel was a simple man to read: He loved to fight, although it was poor form to say so.

Duffié had a prince’s air and a workman’s wrists. A man who fought with sabers needed two things to survive: quick reflexes and strong wrists. During the first year of the war, the cavalry had lost more new men to broken wrists than they’d lost to Rebel bullets.

“You have done well,” the Frenchman told him. “You and your men. The charge this morning was properly done, I applaud you.” He drew out a silver case, offering a cheroot.

Reno accepted: Good tobacco was rare now, and Duffié’s would be fine. “We ought to charge them again. This minute.”

The colonel shrugged and sighed, searching his greatcoat for a lucifer match. “General Averell has his plan. His plan must be our plan. La vie militaire…”

Reno bent from the saddle toward a shared light. The first suck of tobacco came rich and welcome. “Fool’s errand just to sit here. Time’s on their side, not ours.”

“You see this as I do, of course,” the Frenchman said. “But we make no difference.” Across the fields, the Reb guns tried again. Union artillery replied immediately. “I think they will attack soon,” Duffié went on. “They must settle things. Their pride.”

Just as Duffié spoke the last word, a grand line of horsemen emerged from the far groves and swelled over low crests. It looked to Reno as though the Johnnies were going to send in every man they could.

“You see?” Duffié asked. “Their pride, it is always their pride.”

* * *

Major General J. E. B. Stuart led the right wing of the attack himself. He smiled and teased those around him, making a grand display of confidence as every regiment present advanced at a walk.

The Yankee guns had their range, and their shells paced the advance. Stuart felt, again, the loss of Pelham. Young Breathed would do fine, in time. Medical doctor, of all things. Just needed time. But time was an item running short today.

The Yankees had to be punished, humiliated. Beaten down like chicken-killing dogs. Stuart would say it to no man, but he knew the Yankees could not be allowed to build up confidence. Nor could his men doubt their invincibility. So he laughed at untold jokes and remarked, “I do wish the Yankees had brought them along a band. Wouldn’t mind a tune, something with spirit.”

“Catch ’em up and make ’em give us’ns a concert,” a good soul said. “One of them fat German bands.”

“Germans do make fine musicians,” Stuart agreed. Letting Lee set the pace, he waited for the bugle call. Fitz was trimming things awfully fine: Yankee guns were finding targets.

They had to give the Yankees a proper whipping. Send them running. Had to do it. The way they’d done it dozens of times before.

The bugle sounded. The line broke into a canter.

Stuart scanned the Yankee position. Hoping they’d come out. Expecting it. Desiring to meet them head-on in the open.

But the Yankees remained as still as if on a parade ground.

What were they up to now? They had no stone wall here.

The canter became a gallop. The wild yelling challenged the foe, a blood-remembered battle cry from ancient moors and glens.

The Yankees didn’t move. But for the shake of a horse’s head or pawing hooves here and there, the Union line might have been frozen to a man.

Eight hundred riders neared the Union line at full gallop.

Two hundred yards.

One hundred fifty.

Shouting, Stuart pointed with his saber.

One hundred twenty …

* * *

“Carbines up!” The command, repeated instantly, rang down through brigades and regiments.

The Rebel tide seemed about to overwhelm them, unstoppable. But the cavalrymen in blue obeyed their orders, fitting carbines to their shoulders and taking aim.

“Fire!”

The noise punched ears harder than recoils punched shoulders. The artillery discharged canister. The effect was immediate.

Trailing guts, horses shrieked. Forelegs caved, men flew past bridles. Gore swabbed the air. Bleeding riders fought to master their mounts. The luckiest and bravest Johnnies fired useless pistols.

Fresh rounds thrust into chambers. A second wave of carbine fire ripple

d then roared. Troopers reloaded with once unthinkable speed, firing at will as the Rebs sought to recover.

Saving his pistol’s ammunition for the countercharge that would surely be ordered, Reno watched as two flanking guns and his Regulars’ volleys bit into the Rebs. A burst of canister tore off a horse’s leg and the leg of its rider, hurling the severed limbs into the chaos. Reno’s lines were not even assaulted—the Rebel front didn’t stretch far enough. Elsewhere along the Union line, it didn’t appear that a single Johnny got within eighty yards.

Rebs in a confusion of uniforms emptied last rounds from their cylinders and shook their fists. Reno had never seen the Confederate cavalry so easily trounced.

Why didn’t Averell’s bugler sound the charge? With the 5th Cavalry alone, Reno could have struck the Rebs’ flank and rear, could have swept them up. He’d not had such a chance in the entire war.…

“Parker,” he shouted to his adjutant. “Ride to Colonel Duffié. Tell him I need permission to charge, I can finish them.”

The lieutenant needed no encouragement. He spurred his horse to draw blood.

Seconds mattered. As the Union line poured out fire, the Johnnies struggled to restore their order. Their vulnerability would disappear in a blink.

No Union bugle sounded.

Reno was tempted to order a charge on his own authority. But he simply could not do it, he could not disobey a lawful order. Too damned much of an Army man, he thought ruefully, determined never to stand before a court-martial.

He wanted to lash out with sabers, to hack right through the Rebs, cut them all down.

What was Averell thinking? They could sweep them all up right now, for the love of God.

The Rebs began to withdraw. Pulling their horses about and spurring them. Galloping back toward safety.

Darkness at Chancellorsville

Darkness at Chancellorsville Shadows of Glory

Shadows of Glory Red Army

Red Army Cain at Gettysburg

Cain at Gettysburg Valley of the Shadow: A Novel

Valley of the Shadow: A Novel Hell or Richmond

Hell or Richmond The Damned of Petersburg

The Damned of Petersburg The War After Armageddon

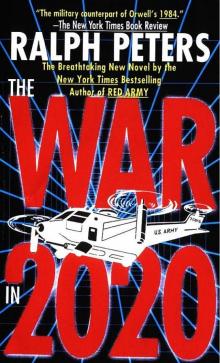

The War After Armageddon The War in 2020

The War in 2020