- Home

- Ralph Peters

Shadows of Glory Page 7

Shadows of Glory Read online

Page 7

Odd, too, that Brinton and I should only have met here, in this pestilential, rat-infested harbor—Cairo was chosen as headquarters solely for its command of the river junction (rivers are everything here, Abel, since the roads are nothing but quagmires). It appears that he and I missed intersecting time and again. Brinton studied in Vienna, at my old hospital, not a year after I fled to Budapest. We have numerous mutual friends and acquaintances, and he shares my curiosity about the theories of Dr. Semmelweis, whose personal demeanor has alienated so many—they say he is a madman, but I only found him a bother. Perhaps this war will bring us an opportunity to test his belief that a surgeon who washes his hands in chlorine solution between operations may reduce the rate of morbidity. I wish no wanton injuries upon our soldiers, but if make war we must, Science should profit.

Anyway, Brinton, who is near the top of the surgeon’s roster (I’m near the bottom, of course), also served as president of the Medical Examining Board in Washington last year, departing just a week before my application was heard. But now we are met, and I find him an excellent fellow, of clear and scientific mind. I sense he was quite lonely upon his arrival here—a western river town is hardly Philadelphia—but he has made himself indispensable to the army and now, with my arrival, he can banter about the old days of his European studies and the like. A local apothecary of German origin even loans us the latest medical journals from Heidelberg and Berlin, where startling results have been obtained in the surgical theaters. Brinton is a sensitive man, for all his social position, and may be gotten to see the need for true equality in time.

Likely, you have not heard much of General Grant, unless you read of the engagement at Belmont in November (not Portia’s Belmont, certainly). He is a brigadier, and my kind of soldier. I cannot predict his worth upon the battlefield, but I like him for his lack of pomp. He is, I am told, an old regular who served in the unjust war of conquest against Mexico, but failed in the peace. His detractors excoriate him as a bankrupt and a drunk, and I think he is watched by General Halleck’s agents on the staff. Yet, I find him a quiet, good-humored man, of sound judgement and inexhaustible energies. His staff gets things done, and I have grown proud of my association with it. Grant is plain and short, and his russet hair goes unkempt. His uniform is proper, but Spartan and devoid of elaboration. He sits for hours over stacks of papers—that bane of war I never had expected—pipe in his mouth, calling occasionally for an adjutant. He reminds me, frankly, of a good surgeon—one who keeps the end in sight and will not be flustered by the radical measures necessary to a cure.

I have encountered a few other ranking officers of promise, although they are only in and out of headquarters, for Grant will not tolerate a lavish establishment. William T. Sherman, who visited, has the fire in his belly, and I would not want to get on his bad side. There is also one Lew Wallace, who writes. He has read his Gibbon and sees the tides at work in the affairs of men. But I fear he may think too much to make a good butcher. I do not like McClernand, who is proud.

You will note a large proportion of Scots among the highest officers, yet I have met no prejudice here against an Irishman such as myself. Well, these Scots are getting their own back on the English aristocrats transplanted to the South, I suppose. I will stand shoulder to shoulder with them, for if any war can be a good war, this is it.

Abel, you cannot imagine the plight of the Negro south of the Ohio! To read about slavery is one thing, and to see its tempered features in the streets of Washington yet another, but this is inhuman! The forlorn creatures run to us, following at the heels of our reconnaissance parties. We know not what to do with them all, and it is, of course, an issue of great sensitivity among the politicos. Grant and his staff wish the poor darkies away, since they become an impediment. But I, for one, am outraged by their suffering.

I must soon close, and apologize for my brevity. I have forgone the privileges of rank (a necessary evil in wartime) and volunteered for medical orderly duty this last eve of the year. It is my gift to those of stronger appetite bent upon celebrating the passing of the old and the coming of the new. There is much to do, for we have an outbreak of measles in the ranks. The men are tall and much to be regarded for their health upon arrival at the camps, but many are farm boys, who matured in isolation. They have not been exposed to those diseases that mark the passage from early childhood, and many die of illnesses an infant would cast off in a week. I study them as a man of Science, but feel their loss.

Tomorrow, Brinton has invited me to dinner to greet the new year, and I will go. He promises me “very good” wine, sent him by acquaintances back in his “civilized East.” I know, my friend, you do not approve of any drink strong-brewed or fermented, but remember the pleasant story told of the Marriage at Cana. If I cannot share the theology of the event, I applaud the sentiment. You know I am no drinking man, yet a glass of wine is a gentle consolation.

Well, I am tame, I assure you. At night, I fall asleep clutching a book. Have you read the Darwin I lent you?

Again, my dearest friend, your first duty is complete recovery. This war can do without you for a few more weeks. Study patience!

Kindly greet Mrs. Jones, and

kiss your little son for,

Yr Obt. Servt.

M. Tyrone

Surg. U.S.V.

Just such a man was my friend, Mick Tyrone. Blunt in his talk, but fine and eloquent with pen in hand. There is education for you.

I read the letter thrice. And then I knelt down in my nightshirt and prayed for all without stinting.

FIVE

I STOOD BESIDE THE PRIEST AS THEY RAISED THE BODY. The hooks they used to find her pierced her flesh and, as they drew her up, I imagined that those irons hurt her still. She rose between the blocks and shards of ice. Dripping deep water, her dress hung sodden down to her bare feet. She had left a second note in her shoes on the bank. Brogans they were, frozen hard. That last message said, “Give the shoes to Annie Slaney.” She must have thought to write it in advance.

The first note, left in her shanty, said, “I am gone to the lock to see my Pat again. Pray care for my babes.” The sheriff showed it to me. It was not spelled so well as I set it down now, but I will not mock her in her death.

I had gone, after a leaden sleep, to the priest’s house that morning. I meant to query him about the affairs of his parishioners, but his housekeeper cackled, “Gone to the locks, ’e is, for the widder’s drowned ’erself and they’re drudging ’er up.” I thought at first that she spoke of the widow of our agent, and I feared vicious murder. But it was not so. This was another widow, one Make Haggerty.

The men tried to be gentle, for they were Irish, too, and she was theirs. But their hands suffered from working in the ice and the water, and they were ill clad, and they wanted to make an end of it. An awkward business it was, reaching poles through broken ice to find her.

The girl come up reluctant. As if mortified by our attentions, and shamed. Hauled up between two floats of ice, she bobbed and sank again, trailing a blue hand. Then a second hook snagged her and the workmen lifted her free.

She was frail. As though she had not eaten in a year. You felt her ribs limn through her soaking woolens. Water poured from her.

And her eyes were open. I know not why, but I had thought the drowned all had closed eyes. Somewhere I read it is a peaceful death. But her eyes bulged in shock, framed by undone hair.

She was not free of the water half a minute before a queer thing happened. The moisture froze upon her skin. In the bright, cold air. A veil of ice covered her face and arms, her fingers and raw feet. The high sun hit her and she shone, a golden fairy dancing on their hooks. Frost gilded her rag of a dress. Ice formed in her streaming hair. She rose encased and gleaming.

They dropped her on the bank.

Her blood was thick with death and the cold, and it made little roses when they worked their hooks away. She lay there staring at Heaven, a magical thing. The priest went down into the gorge

to close her eyes—he slipped and when he righted himself snow covered the backside of his cloak—but he could not make them shut.

He gave up and began to strip off his own garment to cover her, but the workmen dragged a tarpaulin from a shed by the locksman’s hut. The folds were as stiff as her body. The navvies edged the priest away, careful as with an angry dog, and shrouded her in the canvas. Then they removed their hats in expectation of a prayer.

But pray the priest did not. He turned his back on them and started up the slope again, struggling to keep his footing. He wore a poor man’s shoes.

The sheriff had stepped up beside me. “Told you those locks were dangerous,” he said. “Now you see it.”

“I would have thought them well frozen,” I remarked. A smooth, white world surrounded the gorge, and I was mystified. Such a one as her could not have cracked her way down through thick ice.

“They break up the ice on the locks,” Underwood told me. “Keeps the force of it from ruining the machinery and warping the sluice gates. Can’t drain ’em, cause you have to keep pressure up on both sides, or you’d get even worse. And the current still runs down deep. Enough to keep a couple of the mills going. Top freezes up again, and they bust it open again. All winter long. It’s good wages for the Irish.”

The priest looked huge and black as he hauled himself up, grasping at vines and sedge with reddened hands. It was a steep, wild place, with the canal forty feet down. Toward the town, the gorge was deeper still.

Below, the Irish drew straws for who would touch the corpse. Death moves them powerfully, and this one was unhallowed.

“She would have known,” the sheriff went on, “that one. About the breaking up of the ice. Husband was a day-tender on the locks. Before he went and joined up. Decent fellow, no trouble with the law. McCorkle says she got word yesterday they buried him down in Virginia.”

“I hear my name sounded,” Father McCorkle called. As though he would thrash the two of us for taking the liberty.

“Just telling the major here,” Underwood said, “how all this came about. Her soldier fellow getting himself killed.”

The priest steamed from the work of the climb. “‘Get himself killed’ Pat Haggerty did not. The smallpox it was.” He turned his black brows and blacker eyes on me. As if I were the spreader of that disease. “And there’s the fine end to your bugling and drumming. Culling the best o’ me boys with your rumors o’ glory. Oh, there’s a fine end to it, your lordship.” He pulled the black cap from his head and feigned a bog-man’s deference to my uniform. “Will I bow down to ye now, sir, and to your great guns and fine braids?”

“Father McCorkle,” I said, “I’m sorry for this . . . misfortune. But there’s no need—”

“Oh, is there none? Is there none, indeed?” He bore down upon me, and, if I may be honest, he looked more a brawler than a churchman. “An’t it a worse mockery when the lot o’ ye go making a war and turn to such poor, gullible lads as him to fight it for ye? Oh, off they went proud, to be sure. Marching like the boys o’ Vinegar Hill. Pat Haggerty and Brian Brennan and the lot. To join up with the high likes o’ Corcoran and Meagher, to prove the Irishman’s worth! All ‘green flag o’ Erin’ and moonshine. And not the ones we well could spare, no, but the best o’ the boys run off, and husbands and steady workers among ’em.” He bared yellow teeth. “Francie Kilgallen dead at your Bull Run . . .” He eyed the buttons on my greatcoat. “ . . . when the rest o’ ye went streaming off like hoors—”

I was shocked to hear such language from a priest, and fear my look betrayed it.

“—oh, like very hoors ye run. And Michael Duffy done o’ the bloody flux, more glory to ye. And him with a family o’ seven.” His rage grew vast as the sky above us. “And what are the Irish to the lot o’ ye, but white niggers and food for your guns? A feast for your black, murdering cannon.” The fellow actually raised his fist at me. “You’re bigger hoors than the Queen o’ England!”

“Sir, you forget yourself,” I said. “You have no cause to insult the Queen.” My own fist tightened upon the ball of my cane. “And given her own recent loss . . .”

The Lord knows I do not love the English. But I will not have wanton insult heaped upon the good little Queen.

The priest spit on the snow. “That great hoor. The great hoor o’ her. And what o’ the Irish lost to buy her mounds o’ jewels and satins? Starving by the million, with the grain pouring out to fatten the English purse. Driven here in the ships o’ death by the little hoor, they were. And ye,” he said to me, glaring, with maddened eyes, “ye are the worst o’ the lot, ye runt taffies. Naught but slaves o’ the English, ye are, and selling your tiny souls for English gold.”

I saw then he knew nothing of the Welsh, and settled, and let him rant on. Now you will say, “You did not stand up for your kind, and proud you should be of the land of your birth.” But the loss that day was his, not mine, and I saw in that instant the desperate sorrow of the man, and how he only wanted to hurt the world that hurt him and his kind. I was my uniform, not a man, to him.

“And her,” the bull in the cassock cried, pointing down into the gorge. “Our lovely little Maire. Ye know well what ye’ve done to that one, don’t ye? Oh, damned her is all. Even your black informer lies in consecrated ground. But not her, no. She’ll sleep forever separate from her faith.” And weren’t there tears in the big fellow’s eyes as he bellowed on? “Maire Haggerty was a soft one, she was. Not risen to the cruelties o’ your world. Too soft and good for ye. And leaving two babes for to damn herself . . .”

The priest turned away. “Damn the lot o’ ye,” he barked. And he strode across the snow toward the town. Where the canal curved, a few chimneys smoked, marking hidden mills. The black plumes seemed to draw him.

We watched McCorkle go, John Underwood and I, until he was no more than a crow in the whiteness.

“I had hoped,” I said wistfully, “to enlist his aid in my investigation.”

Down below us, old-tongue voices rose. The navvies were hauling the dead girl up the slope.

“Wait until he calms down,” the sheriff said, scratching one of his monumental ears. “He’ll be sorry for taking on like that. That’s just about the worst I’ve ever seen him.” Then he clapped a hand upon my shoulder. “Come on, Abel. We’ll leave it to the coroner’s office now. Give you a ride back to town. Must’ve been some walk out here with that leg of yours.”

We started for his cutter. But then he stopped again, looking out across the fields. Stubble quivered where the drifts had blown thin. The sheriff’s eyes hunted for the priest.

“McCorkle’s not really a bad sort,” he said. “Just takes everything to heart, that’s all. Irish are damned lucky to have him. He keeps ’em to the straight and narrow.”

On the way back into town, with the horses kicking up a diamond dust of ice, Underwood glanced at me and said, “You walked all the way out here unarmed. Didn’t you?”

I nodded. “Broad daylight it is. I saw no—”

“Have a pistol of your own?”

“I do. But—”

“Carry it.”

I WANTED THAT SEWING MACHINE. Not for me, mind you. But for my Mary Myfanwy. It sat there in the window, the very engine she had wished for her Christmas, only to be disappointed by the one who loved her most. Twas a Singer & Co. No. 1 Standard Shuttle Machine, and wasn’t it lovely? All black and trimmed with gold, as if for the royal household. A very panther of a device it looked, as though it would do a wonderful damage to a yard of cloth. And the bitter thing was that it stood reduced for sale. Twas a brute amount still, yet I would have bought it in a minute for my darling, had I held cash money enough that was not come from government funds.

Now you will say, “There is poor economy, for Abel Jones was a well-paid clerk before he put on his blue coat, and now he is got up high to a major’s income. Where is the money of it, and why did he not treat his beloved proper?” Well, I will tell you. I did a curious thing before I

come up to New York. I had been planning it over on my sickbed, and I discussed it with my Mary Myfanwy. She was not without misgivings, and downcast she looked to break the heart, but she knew the man of the house must make the great decisions.

In short, I bought railroad stocks.

Now you will say, “There is wickedness. For the buying of shares is but gambling and speculation, and why not sit you down to a round of American poker, oh, hypocrite?” But I did not think it wrong. I was buying tickets to the future of my new country, see. For my family.

Evans the Bags from the Miner’s Bank tried to dissuade me. Now he is a well-meaning Welshman, though no relation to my wife’s uncle, Mr. Evan Evans, also of Pottsville, or to my buttie Evans the Telegraph. Well, Evans the Bags said the safety of our little savings was best left to the vaults of his bank. But I would not be put off. For in the course of the Fowler affair, I had met one Mr. Cawber of Philadelphia. A rich man he was, and got up there by himself. I come to admire the devil, for he was no more born to privilege than I was. So I made inquiries as to the railroads Matt Cawber was backing, and there I put our savings. In the end, Evans the Bags bought shares for himself, as well. For a Welshman can tell a cow from a calf.

I was resolved that we would not end poor. For there is no country for the penniless, not even sweet America. One day my love would have the finest of sewing machines, and we would not contest the price, unless it were unreasonable. But the joy of that throbbing needle must wait a little.

Oh, yes, I was resolved! I would scrape every penny into our investment! But now, in hard January, the sight of the Singer in that shop window broke my heart. For I would deny my dear wife nothing.

I turned on my cane, careful of the ice, when a beggar boy gave me a tug. Pulling on the flap-over of my coat, all timid like. Then he stood away. Irish he was, by the nose of him, and I do not mean the snot but the puckered shape. Yet, he was American in his speech.

Darkness at Chancellorsville

Darkness at Chancellorsville Shadows of Glory

Shadows of Glory Red Army

Red Army Cain at Gettysburg

Cain at Gettysburg Valley of the Shadow: A Novel

Valley of the Shadow: A Novel Hell or Richmond

Hell or Richmond The Damned of Petersburg

The Damned of Petersburg The War After Armageddon

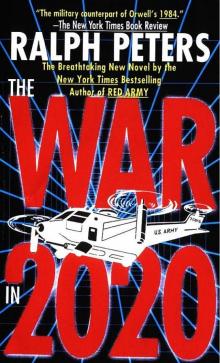

The War After Armageddon The War in 2020

The War in 2020