- Home

- Ralph Peters

Valley of the Shadow: A Novel Page 7

Valley of the Shadow: A Novel Read online

Page 7

“One battery, six three-inch rifles. And one good howitzer.”

Under Ricketts’ whiskers, his mouth formed an acid smile. “Early will hardly be able to claim you had an unfair advantage. Cavalry?”

“Five squadrons of the Eighth Illinois. They’re well officered. And some mounted infantry.”

“So … if my entire division closes … we’d have seventy-five hundred men, at most, a third of them green as shamrocks, with no artillery to speak of and not enough cavalry to picket a field latrine.”

“I do have ammunition stacked. And a train waiting back of the hill to take off the wounded. And we have the river to our front, it’s really a splendid position.”

“And your position is how many miles long?”

“Three. Approximately. A bit more.”

Ricketts sighed. “General Wallace … we haven’t the chance of two mice facing a regiment of cats. You realize this is madness?”

“Yes. I do.”

THREE

July 9, 8:30 a.m.

Monocacy Junction

Amid the scents of fresh hay and charred campfires, Ricketts surveyed the battlefield Wallace had chosen. No one could have selected a better position.

Ricketts’ Second Brigade stretched across the Washington road and into the rising fields on the left flank, with the river a moat to its front. In a hollow off to the right, his First Brigade awaited orders while one last regiment, the 14th New Jersey, drew rations. Wallace’s green troops had been placed in strong positions to the northeast, above the river’s bends, giving them every advantage that could be culled from the terrain. A victory might be impossible, but Jubal Early would face a troublesome morning.

“That’s how you play a low-card hand, son,” Ricketts said to an aide. “Ride down and tell Colonel Truex I want to see him.”

The lieutenant touched the brow of his cap and tugged his horse about.

Ricketts wished he had his division’s complement of artillery, even half of it. There were excellent fields of fire to the northwest, where the Rebels appeared to be taking their merry time. Skirmishing had chipped the air for hours, but Early didn’t seem in a rush to see Washington.

He’d come on, though, before the morning was out. And many a man would have supper with the Devil.

Guarded of speech, Ricketts had not told Wallace how bad things were. When he embarked at City Point, it had been unclear whether other troops would follow. The haste and confusion had been appalling, and he had limited himself to his own concerns, seeing his two brigades marched aboard their vessels. He could only hope that the rest of the corps was on its way to Washington.

The carelessness on every part had been so pronounced, it bordered on frivolity. How on earth could Early have arrived within forty or fifty miles of Washington, shooting his way north for two hundred miles, without anybody in the government or the whole damned Army noticing? Now here he was, James B. Ricketts, lately the proud and aging captain of Battery I, 1st U.S. Artillery, a brigadier general leading men whose spirits were as badly worn as their shoes, soldiers exhausted by two months of grisly fighting and faced with odds as close to hopeless as any in his experience.

Well, Ricketts thought, I’ve been on the edge of hopelessness before, and God bless Frances. He’d been shot four times and abandoned at Bull Run, and his wife had been told he was dead. On learning that he was alive, if barely, and a prisoner, she had bullied her way through the lines and past Jeb Stuart, a friend from their Rio Grande days, to find him in a blood-swabbed, fetid house where she had been greeted by a pile of limbs. His wife had fought the surgeons to save his leg, then traveled along on the prison train to Richmond, insisting on remaining by his side, first in the filthy, sickness-ridden poorhouse, then in Libby Prison, which was worse, begging food to nourish him and accepting bread from a woman of the streets … only to be told that he had been selected for execution in retaliation for the impending hanging of Southern privateers.

Frances had gone to war, threatening to shame the Confederacy before the great, wide world should it execute a badly wounded, honorable officer. Frances, not Jefferson Davis, had won that fight. On the cusp of 1862, he had been exchanged, with his wife threadbare, ill, and beaming by his side when they reached Fairfax.

His Frances, his Fanny, his champion. It saddened him immensely that this proud, determined woman, a distant cousin and far prettier than his own looks merited, tormented herself in the belief that he had never quite gotten over his first wife’s death. And the worst of it was, she was right: Harriet pulsed through his dreams, if he willed it or not.

He had learned as a boy that fairness was foreign to humanity, and nothing in his past had proven otherwise. He had known joy, but never had met justice, not even in sleep. And this day, here in Maryland, promised to be unfair, unjust, and hopeless.

The thing was not to let on.

Anyway, hopelessness lay at the heart of soldiering, did it not? And the odds had been even worse for Wallace before his boys arrived, yet the fellow still had been willing to make a stand. Ricketts could hardly do less.

If Early’s graybacks wanted a fight, he intended to give them one. He only hoped to be as stalwart as Frances.

Hoofbeats. Clattering over the road and pounding a cut field. Trailed by a rider bearing his brigade flag, Truex followed Ricketts’ aide up the slope. Truex had spunk and thrived on hardship, a man who never drank too much or quit a fight too early.

For a last few moments, Ricketts looked away. He no longer thought of wives, alive or dead, but scanned past the low ground and a gristmill to the covered bridge on the left and the railroad bridge on the right, the day’s great prizes. Blockhouses guarded the railroad bridge, one on each side of the river, and Wallace had reinforced them with rifle pits, digging still more defenses to shield the road bridge. Tough chewing for Early’s boys, if the green troops stood their ground.

Truex reined in his horse. Despite the heat, he wore riding gloves.

“Orders, sir?”

“Men ready?”

“Fourteenth’s still drawing. Won’t be long.”

Ricketts nodded. “Had yourself a good look at things?”

“Not bad ground, sir. If we had the entire corps…”

“We don’t.” Ricketts waved off a fly. “Just hope that our last regiments arrive.”

“Rebs don’t seem to be feeling an excess of vigor.”

“Give them time.” Ricketts considered the tiny figures in the fields—not quite a ridge—across the river. He put the range at just under a mile. “They’ll bring up artillery soon, that’s what they’re waiting on. Try to blast us out and spare their men.” He slapped a hand at the fly again, only to have another join the fray. “They don’t want to make a frontal attack, not across that river. No matter the odds.” He looked at Truex. The colonel had a gambler’s face, with noncommittal features but quick eyes. “What would you do, Bill? If you were Early?”

“Flank us,” Truex said without hesitation. “Press our front sufficiently to fix us, find a ford on our left, and turn our position.”

And that will cost them time, Ricketts told himself. Wallace’s vision was downright infectious: They were fighting the hands on a pocket watch, the patch of dirt was meaningless.

“And that’s why I haven’t placed you in the line,” Ricketts told the colonel. “The real fight isn’t going to be down at that bridge.” He pointed leftward, past a fine brick house and into the high fields where his blue ranks ended. Rain-starved corn moved faintly in the breeze, while wheat shocks stood like pegs in neighboring fields. Another house, less grand, could be glimpsed not quite a mile past the mansion, masked by trees above the hidden river. “Those fields. They find a ford, they’ll come across those fields, hollering like devils.”

“I should deploy a skirmish line up there,” Truex said.

Ricketts shook his head. “Not yet. Let General Wallace play his hand, he hasn’t done badly. We’ll call trumps, if we have to.” He

smiled, aware that his smiles were meager things. “Besides, we both could be wrong. Wouldn’t be the first time two old Mexican pistols misfired.”

The situation did remind him of Buena Vista, though. Holding Rinconada Pass with two guns, against impossible odds. He’d been infernally proud of himself, although he wasn’t the glittering sort who gained brevets. But the carnage that had seemed immense in Mexico was almost quaint compared to the bloodletting now.

“If I may ask…,” Truex began in a careful tone, “what do you make of General Wallace, sir? Really?”

Ricketts took the question seriously, since it was one he had been asking himself.

“More guts than sense,” he said abruptly, as if the words had escaped against his will. “More guts than common sense.” He nodded. “And that may be precisely what we need.”

Yet it was clear that Wallace had been out of the war for years, unaware of the viciousness that marked the fighting now, blind to the fact that the best men had been killed and the rest rubbed raw. Ricketts himself had only returned to field command in March, after another ugly convalescence climaxed by distasteful court-martial duty, and the division he had been handed was unreliable. He’d done his best to stiffen the men, but the Wilderness had not added to their laurels. Nor had Spotsylvania. Somehow, though, their performance at Cold Harbor, amid that slaughter, had been superb. He had learned through carnage that he led some splendid regiments—especially in Truex’s brigade—but that others might not bear up under a hammering.

Amid the high fields across the river, explosive billows of dust rose over the Pike. The sudden clouds differed notably from the long, soft plumes that trailed infantry columns.

“There they are,” Ricketts said.

Hand extending the brim of his hat, Truex squinted.

“Artillery,” Ricketts explained. “Can’t see them yet, but those are guns, you can bet your shoulder straps.” He watched as the lead team appeared on a crest, tiny with distance, charging headlong down the Pike. Changing direction sharply, the horses swept rightward into a field, revealing the limber and gun they dragged. Ricketts could almost hear the crack of the whip and the driver’s cries, the slap and jangle of harness—he all but smelled bronze and iron, powder and sweat. The remainder of the battery followed after, cannon bouncing over the furrows and caissons lifting their wheels one at a time, like dogs hoisting their hind legs.

“Twelve-pounders,” Ricketts said. “You can tell by the way they handle.” Then he added, “I damned well wish they were mine.”

9:15 a.m.

Best farm

Stephen Dodson Ramseur handed the message to a sergeant. Possessed of an unerring sense of direction, the man had proven a more reliable courier than any officer.

“Get this to General McCausland. Tell him the need is pressing.”

As soon as he spoke the last words, Ramseur regretted them. The written message conveyed all, and it wasn’t the place of a sergeant to add emphasis.

McCausland had to find a ford, and soon. Attacking that covered bridge headlong would be criminal folly, unless the assault combined with a flanking attack. The whole cursed army would soon be brought to a standstill if McCausland’s efforts failed, but Ramseur feared he’d bear the blame himself.

The sergeant rode off without a salute or fuss. His horse threw dust and pebbles toward the staff.

To Ramseur’s left, a section of Napoleons opened fire. His horse quivered at the first blasts, then stilled again. Positioned in the high fields, the guns could just range the blue lines across the river. Militia those blue-bellies might well be, but someone had tucked them into a grand position—smack astride the Washington road and right above the river. Even the sorriest Yankees could exact a scoundrel’s price, if a man was fool enough to rush them.

Nothing had gone right. Lilley’s Brigade had started late and the passage through Frederick and southward had been slow, with Yankee cavalry needling the advance. Now this: Instead of a handful of Federals at the bridge, it looked to be as much as a brigade drawn up for a fight.

He had sent two reports back to Early, but had yet to receive a reply. Early had seemed to favor him of late, but the old man’s caprices could alter in a blink. If the city fathers of Frederick had put him in a foul mood, Early might even relieve him on the spot.

He needed McCausland’s horsemen to get across that river.

10:00 a.m.

Gambrill House Ridge

“General Tyler isn’t being pressed,” Ross announced, dismounting. “Nothing but skirmishing on the right flank, sir. Lighter than down here.” The aide pawed sweat from the tip of his nose. “General Tyler described the situation as ‘a flirtation, not a courtship.’”

“Let’s hope there isn’t an unexpected seduction,” Wallace said. He still worried over the steadiness of the Home Brigade men, should the Rebels attack in strength. He could not afford to lose the Baltimore road, his only realistic line of retreat. And a retreat was bound to be forced on him at some point, he had no illusions. “No trouble at the fords?”

“No, sir. I rode the entire line. Poison ivy and water snakes, not a whole lot else. The men are ready, though.”

Wallace nodded. “Early has no interest in Baltimore. But General Tyler can’t let down his guard.”

A round of solid shot thumped onto the hillside, bounding past Wallace like a child’s ball refined in Hell. Wary of seeming fearful to those around him, he did not gee-up his horse to move out of range.

An odd thought made him smile, though: If a shot injured the horse he rode, would he be liable, or would the Federal Government? Matters had been so upended that in his haste to reach the junction days before, he had taken the train, leaving his mount, and had rented a gelding from a Frederick stable. The animal wasn’t bad as such beasts went, but it did seem queer to go to war on a rented horse.

A shell burst down in the marsh, making a splash but doing no damage. Soldiers cursed, as soldiers always did.

The initial Confederate gunnery had caused a number of casualties, but the men were under better cover now, in their rifle pits or shielded by the terrain. And Captain Alexander was putting up a fair duel with his little guns, while the howitzer was giving the Rebs a time of it.

Across the river, puffs of smoke marked the fields where men were doing their best to kill each other, a famine-thin blue line holding Rebel skirmishers at a distance.

By Wallace’s reckoning, Early had squandered three hours.

A party of horsemen cantered across the road, coming toward him, their multi-hued banners teased out by their pace. The spectacle put Wallace in mind of the storybooks about knights that had brightened his childhood.

His mood had been much improved by three hours of sleep.

As Ricketts drew close, Wallace said, “Well, General, the Rebs don’t seem too anxious to cross our river.”

Ricketts bent his big torso toward him. “Would you be? They’re not fools.”

“What do you think they’ll do?” Wallace asked.

Ricketts shrugged. “Come around a flank.”

Wallace nodded. “Our left, I expect. Seems plain.”

“I’m sure they’re prowling around right now, figuring out where they can cross.”

“There’s a ford, a fairly good one,” Ross put in. “Down behind the Worthington place. Clendenin has one of his companies guarding it.”

“Watching it,” Wallace corrected. He turned to Ricketts again. “Best we can do, given our numbers. Provide some warning, if they come that way.”

Wallace felt anew how terribly few soldiers he had, even with Ricketts’ division fallen from Heaven. He suspected that all those present were thinking the same thing.

Ricketts leaned toward him again. “Sir, I’d like to push out a skirmish line, a heavy one. Between that brick house and the far one. Can’t quite see the one I mean from here.”

“All right. Good. Just hold back a strong reserve, we’re going to need it. Any word on your other r

egiments?”

Ricketts’ face darkened, answering the question without speaking. Wallace realized again how weary he remained, despite those three magnificent hours of sleep, and how easily he might slip into foolishness. Of course, he would have been informed immediately had a telegraph message come in. And trains didn’t slip past quietly. It had been a fool’s question.

It promised to be a long day.

As Ricketts saluted and turned back to his duties, a rider galloped over the fields they’d discussed a moment before. He was coming from the direction of the ford.

10:30 a.m.

Worthington Ford

“Tiger John” McCausland gave each of his regimental commanders a no-tomfoolery look.

“Here now,” he said, settling his attention on Jimmy Cochran of the 14th Virginia Cavalry. “How many Yankees down there? And no tall tales.” He gestured toward the contested ford, which lay behind a lip of land and below a fringe of trees. The firing was just intense enough to annoy him.

“Billy Vincent says a troop. Maybe two.”

“Damn it, Jimmy. Handful of Yankees? Holding up your boys?”

“They’re tucked into a runt forest. Maybe half dismounted. With those repeaters. Didn’t want to squander—”

“You get on back down there. Dismount your regiment, every man. You open on them from left and right of the ford, but leave the main approach open. Put all the fire on ’em you can, you pin those blue-belly sumbitches to the ground.” He turned to Henry Bowen of the 22nd Virginia. “Hen, you form up in column of fours again. We’re going over this here bump of dirt and straight across that ford. With sabers.”

Bowen started, an almost imperceptible contraction of the muscles, but McCausland noted it. “And I’m going with you. I am sick and tired of all this dawdling. We are going across that ford, and those blue-bellies are going to run like fire in a cotton barn when we do. Then we are going to get up on that high ground and sweep on over those Sunday-best militia boys. And the infantry can lick our tails and call it molasses.”

Darkness at Chancellorsville

Darkness at Chancellorsville Shadows of Glory

Shadows of Glory Red Army

Red Army Cain at Gettysburg

Cain at Gettysburg Valley of the Shadow: A Novel

Valley of the Shadow: A Novel Hell or Richmond

Hell or Richmond The Damned of Petersburg

The Damned of Petersburg The War After Armageddon

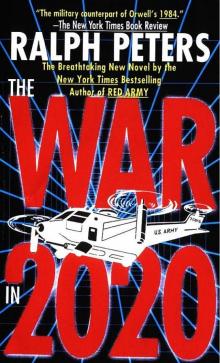

The War After Armageddon The War in 2020

The War in 2020