- Home

- Ralph Peters

The War After Armageddon Page 8

The War After Armageddon Read online

Page 8

Harris chewed on it. For about fifteen seconds. “No. If Monk thinks it’s worth risking his pilots plus noncombatant casualties to get that pass open, I’ll defer to his judgment. Next target?”

“Assembly area outside of Jenin. We have imagery and SF HUMINT on that one. Big target. And clean.”

“Cluster bombs?”

“Mixed ordnance.”

“How many aircraft? Jenin’s getting deep.”

“Four on Jenin. Two on Umm el Fahm.”

“Let’s hope they hit. There isn’t going to be a second chance. Last mission?”

“That’s our request. Since they’re determined to fly. Recce over the Afula defenses. One aircraft.”

“Downlink working? Can it cut through all the soup?”

“We won’t really know until the mission’s in the air. Doubt the WSO will go hot until he’s on final approach.”

“Hate to lose aircrew if we can’t even get the feed.”

“We can always download the images once they get back to Cyprus.”

“If they get back to Cyprus. Mike, you realize what’s at stake, right?”

“Yes, sir. Fourteen Marine aviators. And seven jets.”

Harris folded his arms across his chest. “What’s at stake, Mike, is the future use of air in this campaign. If Monk Morris’s boys go down in flames, I won’t get one damned Air Force mission this side of Iceland.”

“And if they make it back to base? You’ll have a club to beat the zoomies with, sir.”

Harris shook his head. “I don’t want to beat up the Air Force. I just want them to help us beat our enemies.” He grunted. “All right. We’re wasting time. Tell them they’ve got the green light from corps. For all three missions. And God help them.”

THE SKY

Dawg Daniels flew low over the water. Jovial with his subordinates on the ground, the group commander was solemn now. This mission would decide whether he and his men sat out the rest of the war. And Dawg Daniels did not intend to spend his days getting a tan on a beach in Cyprus.

He knew he shouldn’t be flying the mission himself. But none of them knew what was waiting for them — how quickly the radars would pick them up, despite the jamming, whether enemy drones would be flying CAP and waiting for them, how thick the air defenses on the ground would be… or even if the Jihadis’ jammers would screw up their electronics so badly that the patched-with-Band-Aids F/A-18Ds would fall out of the sky.

On the other hand, Daniels was glad to have the F/A-18s, rather than the F-35s that had been taken from them to build out the MOBIC air arm. The F-35s were unable to stay in the air in the hyper emissions environment of the war, where artificial electromagnetic pulses were the least of any digital system’s problems.

You didn’t look down when you were this low. That was the one guaranteed way to go nose in the water. You just monitored the altitude number on the upper right of your helmet display and watched the horizon. Hoping your electronics maintained their integrity and didn’t take you diving for mermaids.

He prayed that all seven aircraft would make it to their targets but figured it was too much to ask that all seven would make it back to Cyprus.

His group’s informal motto was “Semper Fly.” He’d taken a lot of razzing about it when the Air Force pushed through the order to ground all manned aircraft “until the threat environment clarified.” If the blue-suiters didn’t want to go downtown, fine. But Dawg Daniels believed that Marines should make decisions for Marines.

Now he was out to prove that manned airpower was still a player. That pilots were still in the game. And he hoped he wasn’t wasting his Marines’ lives.

Don’t think like that, he told himself. Just fly.

And God, he loved to fly.

Despite the presence of his weapons systems officer in the dual cockpit, Dawg felt peculiarly alone. No intercom chatter permitted until they were on the target run. And no radio transmissions at any time. The only exception was if an aircraft was going down. The codeword for that was “Mudpie.”

Dawg’s initial impulse had been to ask for volunteers. But he decided that was the weak man’s way out of the moral dilemma the mission posed. So he just selected the pilots he thought would get the job done. Rank immaterial. If feelings were hurt, so be it. At least those with hurt feelings would be alive for evening chow.

* * *

Major Robert “Jinx” Jenks saw the cliffs coming toward him. Fast. Five hundred knots of fast. After glancing at his helmet display, he judged his designation and rolled right, hoping his wingman, a mile back and echelon right, was banking just as hard. Screaming over the sunlit waves, Jenks flew as low as he could without dipping his wings, hugging the radar shadow of the ridges. Punching it as if he intended to slam into the rank of cliffs at a forty-five-degree angle.

A lone aircraft shot north. One gleaming speck. Heading for the Haifa Gap.

Dawg Daniels. Good luck and good hunting.

Hold on, Jenks thought. One hundred percent certain that Shimmy was sweating blood in the back seat.

Jenks pulled the old bird right as hard as he could, feeling every seam in the fuselage complain. In a flash, he registered hundreds of vehicles on the strip of beach below. He was flying sideways, fighting to pull his aircraft away from the cliffs. Which were reaching out to grab him.

As he leveled out, tear-off-the-shingles low and heading south, Jenks gave his wings a quick wag.

Next stop, crispy critters for Allah.

* * *

The men on the beach nearly opened fire. Wary of yet another drone attack. When they realized — a thousand men at once — that two USMC F/A-18s were shrieking overhead, a cheer went up that shook the Land of the Scriptures.

* * *

Lieutenant Colonel William “The Willies” Morrison turned his four strikers back out to sea. Just far enough to bank again and go straight in, self-escorted, guiding off the ruins of Hadera and the broken chimneys of his number-one marker, the wrecked power plant on the coast. Ahead and to his left, he saw Jenks and his wing-man scream up Highway 65.

This was old-school flying to Morrison, and he simultneously reveled in it and worried that, without all the magic guidance gear, they’d miss the target. Forbidden even to use the intercom until he had visual, he had to hope that he got where he was supposed to go and that Banger would pick up the target and put the ordnance where it belonged.

The mountains of the West Bank came up fast, a perfect match to the briefing imagery. The problem was what waited beyond the ridges.

The formation he had chosen was unorthodox. Any student who proposed it would’ve flunked out of Yuma, and no O-6 Marine aviator besides Dawg Daniels would’ve gone for it. But Dawg, bless him, just cared about accomplishing the mission. If a Pickett’s Charge of F/A-18s on line was the only hope of putting steel on target and then getting out of Dodge, Dawg was ready to fly top-cover with the chain of command.

Morrison considered himself the least-sentimental commander in the group. But when he thought of Dawg Daniels heading deep in a lone aircraft, his eyes almost teared up.

* * *

Jenks said a quick prayer and shot toward the pass, hoping his attack run would be a surprise for the other guy, not for him and his wing-man. Unable to look down at his knee board and hoping he remembered every detail of the Z diagram for the mission, he switched from air-to-air to air-to-ground mode.

He got his azimuth steering line on the long black snake of the road. Coming in at 300 feet, the earth a rush and a blur.

Time to fly. Four miles out, he popped to just over 4,000 feet, banking to offset 30 degrees and give himself and Shimmy a few seconds to acquire the target.

There it was, right where it was supposed to be. A very busy defensive layout centered on the pass.

“Target captured,” Shimmy said over the intercom.

Jenks put the target below his nose and lined up the diamond, waiting to reach his release altitude as he descended. He hoped his Das

h-2, “Sticks” McCready, was maintaining his interval and not tempted to go down the same chute in this closed terrain. Plenty of bad guys. There was going to be a nasty frag pattern, too.

Jenks felt the lift as the bombs dropped from the wings. Hoping Shimmy could keep the laser on track. Doing it the old-fashioned way. GPS guidance was the stuff of fairy tales now.

“Chicken’s in the pot,” Shimmy told him over the intercom. “Take us home, stick monkey.”

Forty seconds after his pop, Jenks was out of the target area.

“Mudpie!” A single cry, then nothing else. Lowell MacCready’s voice.

“Shimmy? Visual?”

There was a pause. It seemed to last for minutes. The reality was less than five seconds.

“Into the mountain. No chutes.”

Fuck. Fuck. All right. Nothing to be done. Stay calm. Take it home.

But he thought, for one flashing instant, of Lowell MacCready’s wife. With whom he’d slept back at Cherry Point.

Now Sticks was dead.

The terrain was broken, and it was difficult to stay down tight on the deck as he pulled north, then headed west again. Had to hug the approved egress route, stay out of the artillery fan.

Jenks realized that he was drenched in sweat. His flight suit felt as if he’d put it on straight from the washing machine. Sweat stung his eyes, as well.

So much for central air, he told himself. Then he saw the glittering sea ahead.

* * *

Monk Morris wondered if he’d been a fool. Too macho. Too damned pigheaded to be trusted with the lives of United States Marines. Green-lighting those air attacks. Maybe the Air Force knew what it was doing, after all.

He ached for news. He knew that, in the great scheme of the war, seven aircraft didn’t amount to much. But two Marines who counted on him flew inside each one of them. And Dawg Daniels would’ve put his best men in the seats.

Dawg was a can-do Marine. Monk Morris saw himself the same way. Maybe it was a poor combination, he thought. Maybe, at this level, you needed somebody sensible enough to put on the brakes.

He stepped back inside his forward command post and asked, in a voice not quite so firm as he wanted it to be, “Any word on those air missions?”

* * *

Dawg Daniels left the nuclear ruins of Haifa behind, burning sky through the gap and bursting into the Jezreel Valley. So green it hurt the eyes. With clouds of artillery smoke thinning as they rose and spread into the atmosphere.

Big sky, little bullet. He hoped. He’d insisted that the artillery missions continue during his run, figuring that a cessation would alert the Jihadis that something was up. Only the defenses around Afula would be spared. Long enough for him to get clean imagery.

More rounds impacting at two o’clock. Somebody was getting a serious clobbering. Dawg didn’t like the idea of taking shrapnel from a Marine 155.

Well, you pays your money, and you takes your chance, he told himself.

He gave the old aircraft every last bit of juice, popping to 4,800 feet AGL. If the bad guys were going to get him, it was going to be now. While he was riding high enough to get the panoramic imagery that corps wanted.

In planning the mission, he’d rationalized the risk in terms of how many lives good intelligence could save in the coming assault on Afula; he figured an attack on the crossroads town was inevitable. But now he was flying on nerves, not reason, and living second to second. Hoping the pod cameras worked. And that the downlink functioned. And that his WSO wasn’t asleep at the wheel.

The aircraft roared over Afula and banked north. That quick. Pulling so many G’s that Dawg imagined rivets flying off the fuselage like popcorn. He dropped to 500 feet, as low as he could go in the broken terrain. With hills coming up fast, he pulled the aircraft up to 800, then 900.

Getting too old for this, he told himself. But in truth, he felt magnificently alive.

The plan was to leave the downlink — an uplink, really — turned on until they’d cleared Nazareth on the way out. Then no more emissions until they were wheels-down.

Mount Tabor on the right. Gotcha. Here we go. Hold on, ladies and gentlemen.

“One more flyboy visits Nazareth,” Dawg told an invisible audience.

The city sprawled out of a deep bowl, covering the surrounding hillsides with shabby high-rises and haphazard slums.

Every caution light in the cockpit seemed to go off at once. Dawg punched out the flares and switched on the active countermeasures. Nothing else to be done. They had him. It was going to be allemissions, all-the-time now. And some wicked metal.

An explosion rocked the aircraft.

They were still flying.

Come on, baby. Gimme some juice. Let’s go, sweetheart.

Whoomf.

The aircraft shook as if a furious giant had crunched it in his fist and meant to shake out any loose change.

His helmet display died.

Just fly, he told himself. Just fly.

Had to get more altitude. Take that risk. Or he was going to plow a field for Farmer John. Dawg could see the Haifa Gap and, as he climbed, he glimpsed the sea beyond. But he was speeding down a broken road on four flat tires.

The aircraft began to go to bits around him.

Not going to make it, ladies and gents.

He pulled back on the stick until it refused to go any further, altering course to head straight for the Carmel Ridges. Struggling to hold the aircraft together for just a few more seconds. Through sheer willpower. And praying the ejection mechanism was still in working order.

As Dawg pulled high, he imagined his wings coming off. Or maybe it wasn’t his imagination. He tried to level off to eject. But the aircraft was unstable, uncontrollable now, gimp-twitching.

“Eject, eject, eject!” he called over the intercom. Unsure if he was speaking to a living human being.

He punched out. It felt like going through an automobile windshield at a thousand miles an hour. Yank on the neck. His shoulder took a whack.

A reassuring jerk told him his chute had opened.

HEADQUARTERS, THIRD JIHADI CORPS, QUNEITRA

“The Americans are attacking! With aircraft. They’re everywhere!”

Lieutenant General Abdul al-Ghazi remained calm. Someone had to remain calm. The excitability of his staff filled him with a cold, white anger. Would Arabs never learn discipline?

“With manned aircraft, you mean?”

“Yes, yes! Everywhere at once.”

“Then they’re fools. Shoot them down.”

“We are shooting them. Everywhere! Dozens of them. It was only that we were surprised.”

“Then we’ve been surprised twice in three days. When will we stop being surprised?”

The chief of staff calmed down. Slightly. “Insh’ Allah, we soon will drive them back into the sea.”

“But first you will shoot their aircraft from the sky — am I correct?”

“Insh’ Allah.”

“Allah expects us to help. Go back and learn what is truly happening. Their aircraft are not ‘everywhere.’ Are they here, then? Why do I not hear their bombs?”

“I mean to say… that they are attacking at many places. Not everywhere.”

“Find out exactly where. And if you are told that any of their aircraft have been shot down, you will confirm it. I want no more panic. Men with weak nerves are no use to me.”

“Yes, my brother. I only meant—”

“I am not your brother. I’m your commanding officer. If you cannot do your job, another can.”

“Yes, General.”

“Now leave me.”

When he was alone again, Abdul al-Ghazi, the sector commander, thought of two things. First, he thought that he would have very little time to redeem the general situation before the rage of his own superior, Emir-General al-Mahdi, fell upon him. Second, he wondered if the reports that the Crusaders had already reached the suburbs of Jerusalem were true. If that were so, al-Mahdi’s anger mig

ht be uncontrollable.

Al-Ghazi prided himself on being a professional soldier, trained in the old Jordanian fashion, as well as being a soldier of jihad. And al-Mahdi worried him. Clearly, Allah had touched al-Mahdi with a kind of genius. But al-Mahdi had been touched with madness, too. He could not escape the thrall of the past, and he saw everything through the lens of history, as if there could never be anything new in war or this war-torn landscape. Al-Mahdi’s plan of defense had been built upon bleeding the Americans, on the assumption that they would not bear great casualties. But all the reports from the Jerusalem front told of masses of dead and of relentless attacks over corpses.

Was this to be the end of civilization? With the Crusaders returned to rule with fire and sword?

The incompetence in his own ranks outraged him. And he couldn’t fully trust al-Mahdi’s judgment. Hadn’t any of them learned that the way to fight Westerners wasn’t by fighting in the Western way? Despite his formal training, al-Ghazi had little faith in mechanized infantry battalions and tank brigades, in the end. You had to strike the Crusaders where they were weak, not where they were strong.

Still, he was a soldier. He would carry out the mission he had been given. He would make the Crusaders pay a terrible price for staining the soil of the emirate with their boots.

But a part of him asked again: Was this to be the end of civilization? One of the orders given to him bit into his blood like a viper. Would nothing be left for which praise might be offered to Allah? Would the Crusaders destroy everything?

Lieutenant General Abdul al-Ghazi did not mean to let that happen. No matter what strange measures might be required.

He pushed an old-fashioned button on his desk. A moment later, an aide-de-camp appeared.

“Go,” al-Ghazi told him, “but go quietly, and learn if my instructions have been carried out regarding the American taken in Nazareth.”

ASSEMBLY AREA, 77TH MUJAHEDDIN ARMORED BRIGADE

The explosions in the Jenin assembly area continued for an hour after the last of the Crusader planes had departed. No one had been prepared, too much had been done in haste. Stocks of ammunition rent the earth and tore the sky as they exploded. Vehicles burned, and men burned as well. A blackened man with no arms ran about madly, white teeth gleaming where his lips had been, until he dropped over dead.

Darkness at Chancellorsville

Darkness at Chancellorsville Shadows of Glory

Shadows of Glory Red Army

Red Army Cain at Gettysburg

Cain at Gettysburg Valley of the Shadow: A Novel

Valley of the Shadow: A Novel Hell or Richmond

Hell or Richmond The Damned of Petersburg

The Damned of Petersburg The War After Armageddon

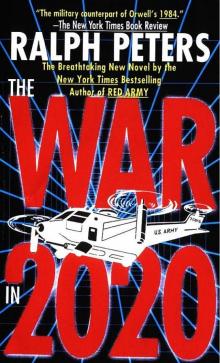

The War After Armageddon The War in 2020

The War in 2020