- Home

- Ralph Peters

Valley of the Shadow: A Novel Page 9

Valley of the Shadow: A Novel Read online

Page 9

Hen Bowen rode up beside him. There was blood on the colonel’s face, but he seemed able. Bowen’s horse bled, too.

“General … General McCausland … they’ll rally, they’re just spooked … give them some time.”

“We don’t have any goddamned time.”

“Just let me and Jimmy rally our boys, they’ll be all right. W.C. and Milt are rounding up theirs.”

“Goddamn it, Hen. If Early hears…”

“He’s done a sight worse himself. Whupped by a pack of coons back of Spotsylvania.” Bowen smiled grimly. “Think he’ll live that down?”

McCausland was in no mood to be appeased. Yet he calmed sufficiently to lower his pistol, panting in the weariness left by fury. But when he considered the inevitable jokes about his nickname, “Old Tiger John turned out to be a house cat” and the like, rage boiled his complexion again.

“Then you damned well rally those yellow sonsofbitches. Damn them all to Hell, they’re going back in.”

“Just give us a little time, sir.” The colonel wiped at his sweat, smearing the blood across his face. “The boys were just surprised, you know how that goes. Even the best troops lose all sense, you give them a good enough shock. They’ll remember themselves and be shamed till they’re mean as hornets.”

“They’d damned well better be,” McCausland told the regimental commander. “Because we’re going to rip the living hearts out of those Yankee bastards.”

Noon

Gordon’s Division, south of Frederick

“How’s that leg getting on?” Sergeant Alderman asked Nichols.

“Tolerable, Sergeant. A sight better.”

“I don’t want to see you on canteen detail again. Unless I tell you to go myself. Hear?”

“Lookee there,” Dan Frawley interrupted. “Jest you look. Yanks are holding on, all right. Smoke an’t backed up one bit.”

Lem Davis shrugged. It wasn’t his fight, at least not yet. Fingering his thornbush beard, he renewed the earlier conversation. “I still say the finest goobers come from down in Sumter County. And I’ll hear no man defy me.”

“Eat some now, I had some,” Tom Boyet put in.

“Think we feed ’em to the Yanks at Andersonville?” Nichols asked.

“Maybe the shells,” Ive Summerlin said.

As if by mutual compact, the sprawled and sitting men looked across the river again, pleased to have the rare chance to sit out a battle and watch.

“I don’t see any real fussing,” Ive offered.

“That there was my point, what I said.” Frawley took off his straw hat. The rim looked mule-et. His long red hair appeared cooked, like it had started out maybe brown and boiled up in the heat. He wiped his forehead with a big, scarred hand. “Nary a man seems hurried worth the mention, just picking and pecking. End up camping right here tonight, things don’t soon start to going.” He considered the prospect. “Tad far to fetch water.” He placed his hat back atop his roasted skin.

Sergeant Alderman slapped at a fly bothering his neck. “Don’t get too far ahead of yourselves, boys. I expect we’ll be eating dust again, headed for Washington. Once they stop their fool play over there.”

Down where the hidden river had to be, black smoke rose, a contrast to the paler smoke of rifle fire.

“Something’s burning,” Tom Boyet said.

“Yanks are smart,” Lem Davis said, “they’ll burn themselves any bridges fit to light.”

“Might be that,” Boyet agreed. He was the smallest of them, but for Nichols. Made tight, though.

“Time to boil up another pot?” Frawley asked Alderman.

The sergeant smiled, which was ever something of an occasion. “How many pots you done cooked up with that dirt you pretend is grounds?”

The sergeant’s easy tone reassured them all. This time, they might just watch other men die.

Nichols had found the talk an oddity as his brethren observed the battle, calculating its course from rising smoke, the noise of the firing, and the occasional glimpse of troops. There had been a good fuss on the right, when a burst of gray smoke had risen above a fringe of trees on the high ground, with plenty of shooting to go along as fixings, but that hadn’t lasted five minutes. The rest of the doings just sounded like more skirmishing, the rifle noise going up and down, without a muchness of guns to give things a shake. His comrades had commented on the fighting as calmly as if sizing up hogs at an auction, almost uncaring about who had the advantage. It was as if they felt duty-bound to be fair, like a prizefight judge come in on the train from Atlanta. They didn’t cheer on their own kind particularly, or damn the Yankees like revival preachers. Lem and Dan, Ive and Tom, they just took it all in, appreciating the finer points of the scrap, like a town man savoring a fat store-bought cigar.

Nichols had prayed another selfish prayer, the kind you weren’t supposed to send to the Lord. He asked that they truly be allowed to rest this day, that just this once other men might bear the burden. His leg remained swollen and discolored, black, purple, and jaundice yellow, although the skin was a little less tight and the lump seemed smaller, if hardened. He had asked Elder Woodfin, the regiment’s chaplain, to look it over the night before, since surgeons weren’t to be trusted. They had prayed together, and Elder Woodfin had assured him that his leg would be fine.

Still hurt, though. And his new shoes had not been a perfect blessing, not even after he cut his toes free from their prisons.

But he’d marched all the way and meant to keep on going. No man would call him a skulker, now or ever.

“Yes, sir,” Lem Davis said, slow-voiced and pawing his beard. “Those Yankee boys are burning themselves a bridge. That’s old wood smoking.”

“Could be a field caught fire,” Tom Boyet said. But he was a town man.

“Ain’t no field. That’s wood smoke,” Ive Summerlin seconded. Ive’s voice remained sharp at the edges. There had been no word of his brother.

As the firing lulled again, Lem Davis took up a scrape of dirt and let it sift through his fingers. “Grant ’em the drought, and it still ain’t the soil back home.” His eyes left them. Thinking on that farm that was no good to him now, Nichols figured. And on that young wife dead.

Just to be contrary, Dan Frawley told him, “Seems right fine to me. Even better, back on that farm yesterday.”

The heat pressed down on their words as heavily as it weighed upon their bodies. Dan tended to the coffee. Nichols didn’t want himself a cup, but looked forward to it anyway. Drinking coffee together kept things right.

Lieutenant Mincy wandered over. The man had a nose for coffee sharp as a patteroller’s hound.

“Why, if’n it isn’t Lieutenant Mincy!” Frawley called. “Any sign of those famous Yankee rations we heard been captured? Officers eat ’em all up?”

A decent-natured man most all the time, Dan was tetchy about the way officers grabbed up captured vittles. Officers had to pay for their food from the commissary, so they didn’t miss an opportunity to eat for free at Abe Lincoln’s expense. Sometimes there was a plenty to go around, other times there wasn’t.

That was a plain fact. But it was another fact, and every man knew it, that General Evans, a perfect Christian or nigh unto one, never took more than his share, and rarely that much.

“That coffee boiling?” Mincy asked.

“No, Lieutenant,” Lem teased, “that’s possum stew. Just a little thinned out.”

Dan was bewitched by the thought of those captured rations, though. He was a big man, plow-horse big, with an appetite near sinful. “Wouldn’t do a man any harm, get a powerful meal in his belly,” he told them all, closing his eyes and tucking back a strand of that clotted red hair. His voice took on the reverence due only to thoughts of salvation, not this earth. “Tin or two of Yank sardines, some cheese. And biscuits, place of crackers. With real drippings. And meat hasn’t yet been salted down and don’t war agin’ a man’s jaw. Wouldn’t mind none where I found it, neither.”

> “We’ll be marching long before a good feed comes along,” Alderman said sharply, spoiling the tone. There was a rusty nail betwixt him and Mincy, who had been lifted up from third sergeant. No one really begrudged him the promotion, not even Alderman, really. A brave man, if a thirsty one, Mincy had been wounded twice—right bad at Gettysburg—but came on back for more. But every man needed a bone to gnaw, and Alderman’s bone was Mincy.

Food, real food, had savored up in every mind, thanks to Dan’s dreaming. Lord, though, Nichols thought, wouldn’t it be fine to share out a big, fat ham among my brethren? Wouldn’t that be a blessing?

Someday … if the Lord spared him … he was going to go home, marry a good Christian woman, and know a hot dinner waited for him every single day for the rest of his life.

General Gordon rode across a near field, with General Evans at his side and their aides keeping their distance. Usually, each man greeted the troops he passed, Gordon erect and nodding slightly, a kingly man, a Joshua, and Evans smiling and waving, an expression on his face just short of shyness. Today, though, they just rode on by, Gordon stern as a Patriarch confronted by Sin Incarnate, as Elder Woodfin put it, and General Evans looking troubled as Job.

Job had three daughters, Nichols remembered. That always stuck in his mind. Jemima, Kezia, and … Nichols found he could not recall the third name, which troubled him greatly, for he prided himself on his knowledge of the Good Book. It dogged him wicked, that missing name. But he did recall the next verse, which began, “And in all the land were no women found so fair as the daughters of Job.” Nichols always wondered what Jew girls looked like.

Such pondering was meant for another day, though. He’d observed General Gordon enough times now to recognize that impatient-of-the-fool-world look he took on. It meant that Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego were headed back into that Fiery Furnace soon enough, and a man had better pray that the Lord felt merciful.

FOUR

July 9, 12:30 p.m.

Gambrill House Ridge

From his vantage point on the high ground, Wallace stared at the burning bridge. He had not wanted it put to the torch so soon, merely readied. His order either had been misunderstood or had been flawed—a possibility he could not discount, given his weariness.

No matter the fault, it was his responsibility, and he accepted it. He long had believed that the lowest thing an officer could do was to blame his subordinates for his mistakes and failures. He had seen enough of that out west, under Halleck.

The worst of it was that more than two hundred infantrymen, a mix of raw Home Brigade men and a detachment of Ricketts’ Vermonters, were all but cut off on the other side, their only path to safety the open deck of the rail bridge.

Nor did he want them to panic and quit the fight. They were buying time cheaply, measured against the great scale of the war. He understood, full well, that it didn’t seem much of a bargain to the men in combat along that rail embankment or defending the blockhouse, but they were doing heroic work in a hard hour. He hoped the veterans would prop up the morale of the Home Brigade soldiers sufficiently to keep them potting Confederates.

They had done surprisingly well thus far, repelling every probe, as well as an attack that came sneaking along the river. But he needed them to buy a bit more time. For him, for Washington.

The bridge was an inferno now, flames peaking and timbers crashing. The men who set the wheat shocks to fire the bridge had done a proper job.

One more problem for Early.

Not that Wallace lacked problems of his own. It had been a terrible hour. Even before some enthusiast set the bridge alight, bad news had tumbled over him. First, the telegrapher fled, cutting his communications. Then, when the first wounded men were carried back to the evacuation train, the locomotive was nowhere to be found. The engineer had driven off at the first cannonade. Next, the howitzer, his only heavy artillery piece, had been fouled by a nervous cannoneer dropping in the shot before loading the powder. Despite every effort, the gun remained useless and likely to stay that way. And the Johnnies continued to deploy additional batteries, keeping up a relentless bombardment.

Ricketts had done splendidly, though, repelling the first significant attack. But Early was just getting started, and those high fields would allow Reb numbers to tell.

Grateful for Ricketts—immensely so—he applied himself to shifting his meager reserves, dispatching staff men to trouble spots, and disbursing ammunition with largesse—it wasn’t the time to be thinking like a bookkeeper.

He stilled his horse and drew out his pocket watch. It ran a bit fast, but Wallace was pleased to see the hands marking twelve forty. He had stolen six precious hours from his enemy. If he could hold three hours more, Early would have lost the best of the day.

Why wasn’t Early pressing harder? Why?

1:15 p.m.

Best farm

Ramseur knew he was about to taste some bitter medicine. He only wondered how large the dose would be.

Early looked hot as a Tredegar furnace. Chawing, spitting, and glaring. Usually, the army commander unleashed a barrage of profanity the instant he faced a man who had disappointed him. But Early only spit and stared hot lead, interrupting himself with glances across the river, working his cud of tobacco as though grinding a living thing to a painful death.

Quiet as Presbyterians on Sunday, the staff officers about kept a wary distance.

Desultory skirmishing continued in the low fields, by the rail embankment and river, and the guns kept up their bombardment of the Yankees, but it all seemed weak-loined and feeble to Ramseur now. And the devilish thing was that an aide had just delivered a letter from his wife that he ached to read: With a child on the way, her frailty had become worrisome.

At last, Early spit out his entire chaw, a monstrous clump, and said, “God almighty, Ramseur, why the hell aren’t we over that little creek?”

“General Early, the Yankee position is—”

“I didn’t ask you about the damned Yankee position. I read your messages. And I’ve got eyes in my head. I asked you why we’re not across the river. And you let them burn that goddamned bridge.…” He turned to General Breckinridge, who had ridden over with him. “Ever feel you been pissed on by your own dog?”

Ramseur tried again. “Sir, General McCausland sent a message not ten minutes ago. He’s preparing to attack again. He’s certain he can sweep the Federals away.”

“Ha!” Early said. The pitch of his voice went higher, near to a screech: “McCausland couldn’t take a shit without being led to the outhouse.”

Twisting his bent spine, Early demanded his field glasses from an aide. But he had not looked through the lenses for a full minute before he handed—almost threw—the binoculars back to the captain.

“Can’t see worth a damn from up here.” He bobbed his head toward Ramseur. “That’s your damned problem. You’re not close enough to see a goddamned thing.” And to Pendleton: “Sandie, stay here with this gussied-up flock of geese passes for a staff.” He pointed to the aide who bore his binoculars, a new addition whose name he could not recall. “You ride on with me.” Turning again, he said, “And you, General Breckinridge. You come along. And you, Ramseur.”

“Where are you going, sir?” Pendleton asked. “In case I need to find you?”

Early snorted. “Not so damned far.” He pointed. “Just to that cracked-open barn down there. See if we can’t find the battle.”

Ramseur reached for Early’s bridle. “Sir, that barn’s within range of Yankee sharpshooters. Their artillery shot our men out of it.”

Early glared at him. “Hell with Yankee artillery. I can’t see, I can’t command. I can’t command, I might as well go home to Rocky Mount and drink my fill of Brother Cantwell’s whiskey.” He kicked his horse into motion. Then he yelled back, “Flags stay here. Just get in my goddamned way, all you’re good for.”

For all his age and deformities, Early could ride. He galloped down through the fields at a pac

e Ramseur found hard to match. Breckinridge lagged behind and seemed content to catch up when he could.

They weren’t in front of the barn more than a few seconds before bullets started hunting them. Early pretended he didn’t notice. Determined to show his own mettle, Ramseur played along. But his thoughts strayed to his wife and the child she carried.

“Them glasses,” Early said.

His aide handed him the binoculars.

As he scanned the enemy position across the river, Early let his horse nose trampled hay. The army commander grunted now and again, stopping once to claw at his tobacco-juice-stained beard before raising the glasses again.

“Smart,” he said. “Give ’em that.”

He moved the glasses along to the right. Then he stopped, straightening his humped back so abruptly that Ramseur expected to hear a mighty crack.

“God almighty,” Early said. “Those are Sixth Corps flags.” He lowered the glasses and fixed his attention on Ramseur. “And you didn’t even know. Did you?”

Ramseur said nothing.

Early took on his most sarcastic look and spoke, loudly, to Breckinridge: “Didn’t even know he’s facing Sixth Corps boys, when all he had to do was goddamned look.”

For an ugly stretch, silence gripped the generals. Despite the shot and shell, each man held still.

Ever the politician, Breckinridge tried out his make-peace voice on Early: “Doesn’t look like more than a brigade.”

“Wherever there’s a brigade, there’s a damned division.”

Early plunged into activity. Tossing the field glasses back to the aide, he told him, “Ride like merry hell back to Colonel Pendleton. Tell him General Rodes needs to give them a push on the Baltimore road, take him some prisoners. I want to know if we’ve got Sixth Corps boys there, too. You understand me?”

The aide dug his spurs into his horse’s flanks.

“Ramseur, you get back to that clapped-up multitude of yours and start pressing hard on those buggers this side of the river, just clear ’em out. Get your paws on that railroad bridge, at least.”

Darkness at Chancellorsville

Darkness at Chancellorsville Shadows of Glory

Shadows of Glory Red Army

Red Army Cain at Gettysburg

Cain at Gettysburg Valley of the Shadow: A Novel

Valley of the Shadow: A Novel Hell or Richmond

Hell or Richmond The Damned of Petersburg

The Damned of Petersburg The War After Armageddon

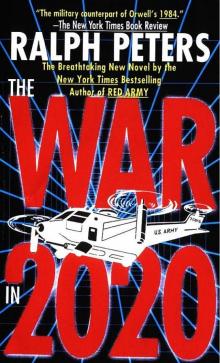

The War After Armageddon The War in 2020

The War in 2020