- Home

- Ralph Peters

Shadows of Glory Page 10

Shadows of Glory Read online

Page 10

“Suffering,” Mr. Morris repeated, “terrible suffering . . . human bondage . . .”

“Now you take John Brent,” Mr. Douglass went on. “Employed in a livery stable, yes. Although few people know that he is also half owner of the establishment. Some achievements are best enjoyed quietly, and a man must reckon his circumstances. But I will confide in you, as an agent of Mr. Lincoln’s government: John Brent has been one of the great heroes of the underground railroad. Surely, Major Jones, you have heard of that desperate path to freedom?”

I nodded, for I had. My Mary Myfanwy had long been a great one for the emancipation of the Negro, and had tugged me to not a few lectures upon the subject back in Pottsville.

“Well, the underground railroad ran heavily along Keuka Lake here. Fortunately, we have ever less necessity of it now. But even in recent years, there was great danger,” Douglass said. “Greater danger than you might credit. Slave-catchers, rewards, nightriders, the kidnapping of Negroes born free . . . none of it frightened John Brent. He would walk from here to Bath to lead our people to freedom. Why, he must know these hills better than any man alive. And a tireless man. Fearless. Yet careful, for bravado is the enemy of such enterprises. Still,” that son of the equator concluded, “I understand he barely escaped the mob and a noose during the Dundee troubles, and remains unwelcome in some corners.”

“Dundee, Dundee! Elder of the church, as well,” Mr. Morris exclaimed. “An elder! You’ll hear him in the choir this very night, at evening meeting! Evening meeting, Brother Jones!” His hair seemed to rise higher with his excitement.

Look you. I would have enjoyed an evening of prayer and community, for such is ever a comfort. But I had not yet done my full day’s work. I had one last call to pay.

“I would come, sir,” I told Mr. Morris, “and most rapturous. But government business intrudes, see.”

“But where will you go, where will you go?” the pastor asked, in Christian disappointment. “It’s night, night!”

“I believe the Catholic evening worship finishes soon?” I drew out my pocket watch to verify the time.

“Yes, yes. Gone to their drinking, gone to their drinking. Not like honest—”

“Well, then,” I said, already done with my starve of a supper, “I will call upon Father McCorkle, for we parted upon a break that must be repaired.”

“McCorkle? McCorkle? Surely, he could wait . . . evening meeting . . . congregation . . . meet the congregation . . . honored guest . . . honored . . .”

“I fear,” Mr. Douglass interjected, with his deep eyes upon me, “that we are both disappointments to Mr. Morris. For though we share a commitment to abolition, I cannot share his . . . beliefs. I have moved onward.”

Disappointment there. For such a grand fellow as he should have been a paragon of faith.

I am a plain man, and Mr. Douglass read my thoughts more clearly than the girl had done.

He smiled. Twas a request for understanding, that little twist of the lips. “I have no wish to offend . . .” He nodded to Mr. Morris. “ . . . our gracious host.” He turned his prophet’s eyes back to me. “Or you, sir. Good men may have differences, yet work toward noble goals they hold in common. But I will not dissemble in the matter of religion.”

I pitied the great fellow then, and not for his sable skin. For he was a handsome creature. But can you imagine the loneliness of men without faith? I thought, of course, of dear old Mick Tyrone. And now I recognized the sorrow that followed Mr. Douglass like an echo. They bent over books in their longing, and failed to lift up their eyes to the light. Now I like a good book, mind you, but would not trade my faith for all the libraries of London. Even if their science proved me wrong, I would believe. For there is no other lasting comfort, and kingdoms are nothing.

We all stood up to part. Mr. Douglass reached into his vest and drew out a card.

“I’m off to Rochester early in the morning,” he told me. “So we may not have an opportunity to say farewell.” He looked down at me, for he was a tall one. “I hope you have more good out of old McCorkle than I did, sir. No progress at all. Nothing to show for the time and effort. He’s so pigheaded about his beloved Irish. And I’ve got a paper to publish.” He offered me the calling card, then his strong hand. “If your duties ever bring you to Rochester, I would consider it an honor to be your host, sir. The world is short of heroes nowadays.”

“I’m not—”

“No demurrals! No demurrals!” Mr. Morris insisted. “A hero, a hero!”

Douglass released my grasp. I had no inkling of the greatness of the man at that time, for I can be near of sight in some things. Nor did I have any notion of the disappointments that awaited him. But let that bide.

“I’ll stop by the stable on my way to the train in the morning,” he added, “and have a talk with ‘Reg’lar John.’ I’ll tell him he can stop that good-darkie nonsense with you. He and I . . .” Here the great fellow’s eyes clouded. “We both began our lives on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Under circumstances foreign to human decency. We understand each other, John Brent and I.” Then he snapped himself out of the past and repeated, “If you’re ever in Rochester, Major Jones . . .”

“Time for chapel! Time for meeting!”

The truth was that I would have preferred to follow the Reverend Mr. Morris into the meeting hall, where my fellow Methodists were already gathering. For I had need of succor. And I will tell you: Selfish Abel had no wish to trudge off through the cold and dark. It is a weakness, how we love our comforts. But a Welshman is a dutiful fellow, most terrible in his determinations, and twas time to take matters in hand.

FATHER McCORKLE ANSWERED the door himself. The pleasure on his face was sublime.

“An’t it the good Major Jones himself? Sure, and a blessing it is that ye’ve come to me door. For wasn’t I thinking upon ye but now, and shaming meself for me doings and carryings-on? And here ye are, man. Made flesh, upon me word!”

Well, that was a change.

The fellow invited me in. Lean it was in his shiver of a house. Seizing my coat, he set me a chair by his own, close to the hearth. He poked up a blaze with a quivering hand and his shadow grew gigantic on the back wall. “And don’t the winters seem longer with the years, boyo? But the years themselves grow shorter . . .” The firelight hunted over the crags of his face and the dark cliff of his brows. “Now Mayo’s a hard place, ye know. But her winters are naught, held up to those of New York.” He sighed. “When I was young I took meself to Rome, by the Grace of Our Lady, and wasn’t that lovely and warm? Tis a joy in the memory.”

We sat down. “Will ye have tea?” Then he gave me a wink. “Or there’s not a bad poteen I can offer, for they bring it along to soothe me.”

“I have taken the pledge, sir.”

He raised his chin and lowered it again in approval. The firelight left half his face in shadow. The stern man of the burying and the titan of the morning were gone, leaving a worn old fellow behind.

“Oh, and a grand thing that is, the Temperance! I give poor Morris that, for all his follies. He does keep his flock off the bottle. Tis a curse on the Irish, the drink. But then so little they have . . . will it be tea, then?”

“I would join you, sir. If you’re having a cup yourself, see.”

He set a kettle over the flames, then parsed out leaves that had been used and dried. His furnishings were but sticks, dusty even in the dark. Twas a poor place set beside our Methodist comforts.

He drew his chair closer to mine. Until our knees all but touched.

“Oh, I’m a proud one,” he said. “Tis my besetting sin. And so I delay. But there’s no avoiding the act o’ contrition. Sorry I am for my cursing o’ ye. For the language. And for the sentiment, as well. Wrong it was, and wrong I was. Though disagree we will o’er Victoria Regina. No, ye just got in the way o’ the storm and it blew on ye.” He looked at me, but his eyes were lost in canyons of shadow. You saw but a gleam. “Am I to have forgiveness, then, M

ajor Jones? What shall be penance enough?”

“Sir . . . we are all sinners . . . I’m hardly in a position . . .”

A slender log broke crisp and sparks rained upward, lighting a volume of Tacitus the priest had set aside.

He smiled and bent to turn the kettle on the irons. “Oh, ye Protestants. Couldn’t I weep for ye, though? For ye do not understand the glories and gentlings o’ forgiveness. It is a thing the True Faith has, if naught else . . . but are we mended then? Can ye overlook the madness that come upon me?”

It had been a great day for madness.

“It is behind us, sir.”

“I thank ye for the kindness o’ that! As I thank the Lord and his archangels.” A veil of sorrow settled over his features. “The girl, it was. Our little Maire.” He shook his head. Slowly. “The Lord has His wisdom, sure, and it is not upon the likes o’ us to question it. But times there are when tis hard. For He calls the good wine to Him, and leaves the dregs behind.” He searched my face, my eyes. “She was good, and wronged by this life.”

“A tragedy,” I said.

He mused on that. “Too small for a tragedy. But a sorrow . . .”

The kettle called. He lifted it barehanded from the irons and set it by while he dusted the tea leaves into a chipped pot. He poured the water slowly, with the steam rising about his hand. Twas as if all things in his life had to be measured. The carefulness of Mr. Morris’s table was luxury to this.

“Sugar there’s none,” he said.

“There is good,” I lied. “For I do not like sweetenings.”

He raised one end of that line of brows. “And I thought the Welsh were great ones for their sugaring?”

“I have known such,” I said. “But would have mine hot and clean.”

“Hot it will be, then.” He did not steep it long, but poured the pot empty, straining the beverage through cheesecloth to collect straying leaves. He handed me the better of his cups. The tea smelled sour, but the cup was lovely warm in my hands.

“Now ye’ll be asking me,” he said, seated again, “about all the bad doings amongst us. The lad bedeviled and hung, and your Federal man took up before him. And rumors o’ rebellions and risings. Will ye not?”

I nodded.

“Tis to be expected,” he said. “For ye have your duties, as I have mine. But there’s sad little I can tell ye. Even was I to parley the secrets o’ the confessional, which I am not like to do. But there’s this much sure: Neither rebellion nor insurrection against the government. For what’s to be gained by the likes o’ that? No risings nor revolutions, Major Jones. But if it’s unhappiness of which ye talk, you’ll find a plenty. For the poor are always with us, and injustice. The hatred of Cain is upon the land.”

The man looked even older now.

“But . . . if there’s no plan of rebellion . . . if there’s nothing,” I said, “then why kill a Federal officer? And an employed agent?”

“A ‘spy,’ ye mean. For let us be plain. Oh, ye do not understand the Irish a jot, if ye fail to see the terrors an informer holds for them. Tis the bane of our nation’s story, the informer.” He leaned closer, lowering his teacup. “And what did ye hope to gain by such recruitments? Surely ye see that the silver of Judas only buys lies when the truth will not do? Tall tales he will tell ye, all smothered in a cream o’ fine words. No, I will tell ye the truth of it—informers will be rooted out and done with. That is the way of it, and not even I could stop them. Though I will not excuse murder. No, there’s no taming the wildness in them when they smell the stink o’ the spy among them. Tis the way o’ things, and a lesson taught by Britannia.”

“And the Federal agent? Captain Michaels?”

“Sorry I am for the loss o’ him. But there’s nothing I can tell ye there. Mayhaps he crossed the wrong man, or the wrong line. They say he was a drinker himself, your Captain Michaels.”

“Father McCorkle”—I called him “father,” for that is how these people would be addressed, and meant it only as politeness—“surely you see that the government must pursue the matter. Look you. Two men dead. And killed ugly. The law will have its way.”

He weighed an empty palm. “I cannot help ye. For I know nothing.”

“But will you keep your ears open? Surely, you see the danger to your flock. I speak of prejudice, sir. America has been a ready refuge to the Irish, but murder will not be condoned and what will good citizens think—”

He closed a big hand over my knee. Twas my bad leg, but no matter.

“Speak ye o’ America? And of a ready refuge? When men are paid starvation wages, and their women less than that? Do ye know, man, that I’ve so many cannot afford to marry that there’s less being born than dying amongst us? They go talking o’ Irish immorality, the fine ones. But let them look close and honest, and a sad crop o’ spinsters they’ll see, withering away. And young men all longings and rags. No, I’ll never put the joys o’ Temperance in their heads, though I shout meself blue in the face. For the lot o’ them are naught but looking for a way to numb the pain till they’re called.” He sat back in his comfortless chair. “Maire Haggerty now. Who’s to say she wouldn’t have been better for the comfort o’ drink than damning her immortal soul with her doings?”

“This country,” I said, “is man’s hope and pride. Now, in its hour of peril—”

He stood up. For he was past listening, though his mood fell short of anger. “Will ye come with me this half hour?” he asked. “For as ye lay claim to being a Christian man, there’s a thing I would show ye.”

“I am at your service, sir,” I said. For I meant to indulge him. He was a compelling sort, and I wished to mend our relations. I recalled the drowned girl, frozen and shining, and the priest’s rage above the canal. Twas all Heaven had been the object of his anger, and not small Abel Jones.

He tamped down the fire to ward off a conflagration, then pulled on the black cloak that served him for a winter overgarment.

“Come with me,” he said, “and I’ll show ye a thing.”

We went along the darkened street, past little houses closed against the cold. He led me toward the canal. The houses became shanties, and the shanties grew smaller. Off to the left rose the black wall of a mill. In low barns, mules complained. Along the outlet, the barges were moored in ice. Kerosene lamps glowed behind the shutters and oiled-cloth windows of the cabins on the decks.

“The poor devils live on the boats year round,” the priest told me, turning us right toward the lake itself. “For the canal’s all a world o’ its own, and a poor one for those that take their living from it. And the railroads go making it harder. For your locomotive needn’t wait for spring and the thaw.”

He near made me feel guilty about my investment. But progress is ever hard. I had seen that in the wretched streets of Merthyr, where I come into my young manhood.

“I had an encounter last night,” I said, tapping along on my cane, “with a fellow who calls himself ‘the Great Kildare.’ He is of your country and faith, I believe?”

I felt the priest go darker than the darkness. “Perhaps o’ me country, but not o’ me faith, that one. Not with those doings o’ his, and naught to it but eternal damnation. Tis Satan’s business, and no less—and your Mr. Morris entertains the fellow! Wickedness and damnation!”

Now I had expected as much from him, for the Catholic faith is stern down deep, while ours is stern on the surface. But I did not expect the change that next come over his voice. For it softened.

“And yet I don’t truly know the man,” he said. “And there may be good stirred in with the evil. For the world is not so clear as you people would have it.”

“Perhaps . . . there is good in the daughter?” I was testing him. For she had claimed the priest as her protector.

“I hardly know her but to see,” he said. “Though I keep the worst of them off her. They’d kill her for a witch, if not for her beauty alone. She sets a fear in men, that Nellie. And worries them with wanting, besid

es.” He sighed, and a fog of breath preceded his next step. “She’ll be damned as sure as her father, if she doesn’t turn back to the church before the cough takes her.”

“She’s very ill,” I said. “She—”

But then I heard the music. It come jigging through the darkness. A dollar fiddle and a squeezebox, played to the pulse of a flat drum. Faint it was, but fevered. Growing louder with our steps. The path turned by a boathouse. Across a waste of snow, a barn bled light. Or perhaps it was a warehouse. For it was set by the water. Ramshackle, anyway, and overflowing with humankind. Those who could not get inside danced by a rubbish fire. Wild as the Pushtoon, they were, when that murderous savage capers to his war drums.

I expected the priest to put a halt to the business.

But I was wrong. He kept his silence, and the great dark shape of him hardly disturbed the revelers. A few cast wary looks upon our approach, but soon went back to their joys. Twas as if the priest had left his own dominion and entered another where his law did not prevail. We seemed but half visible.

Spirits, see.

A fighter-faced fellow leaned by the door, collecting the penny admission. He let the priest by unmolested, but had his cent of me. I did not like his eyes. Or the hammered look of his flesh, or the twist of his nose.

But in we went. A few of the young girls calmed their reeling at Father McCorkle’s entry, lowering their skirts again to cover their petticoats. Even then, they swirled on, no more demure than the famed Spanish dancers of Gibraltar, whom I had seen when my India-bound ship put in—I was a foolish fellow then, and young.

But these girls flew! And not the girls alone, but the men, by whom the fairer sex was well outnumbered. Fellows danced with fellows, grinning silly. Couples past their best years trotted, too. There was but a small stove set in the corner of the vasty place, but the air was tropic hot and wet. The entertainment stank of sweat and whisky.

We stood at the back, the priest and I, amid the old men with their pipes. I watched the turning faces. Is anything more hopeful than a young girl at her dancing? With all her dreads suspended, and the moment a cloud of thoughtless beauty? Now there are those who would condemn such pastimes, and right they are that we must beware lasciviousness, for temptation is like any danger and finds us stronger on one day than another. Yet I would not forbid the dance, so long as things are done proper. For there is joy in the stepping, to be sure, and joy is a thing of sufficient rarity. I will even admit to tapping along with my cane, although I made no vulgar display.

Darkness at Chancellorsville

Darkness at Chancellorsville Shadows of Glory

Shadows of Glory Red Army

Red Army Cain at Gettysburg

Cain at Gettysburg Valley of the Shadow: A Novel

Valley of the Shadow: A Novel Hell or Richmond

Hell or Richmond The Damned of Petersburg

The Damned of Petersburg The War After Armageddon

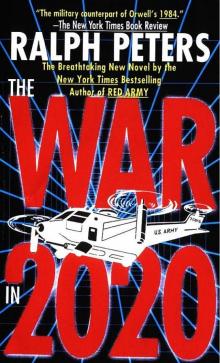

The War After Armageddon The War in 2020

The War in 2020