- Home

- Ralph Peters

Shadows of Glory Page 11

Shadows of Glory Read online

Page 11

Their faces careened before us, and soon the priest was forgot. The girls picked up their long skirts again, and, proof of the devil, I caught myself looking once. For I am not invulnerable to beauty, though a married man and content.

But their faces! If the priest had no dominion here, neither did misery, or poverty. For an hour these gay carousers reeled free of care. They whirled and laughed the darkness down, some aspects fair, others gray and toothless. Wart noses and cleft lips, or soft cheeks pinked by exertion, from handsome to haggard went the run of their features, from moony, pudding faces or chins as sharp as blades to the colleen splendor of young darlings. Some were clean, while others staunched the cold with layers of dirty woolens, but all had succumbed to the joy of the music, and the hoopla wildness, and the freedom of brief forgetting.

The priest said naught, but let me watch unbothered. And then, with the fiddler and squeezer and pounder gone off for a moment to fuel themselves up, a young man took the stage, led on by a baldheaded banty. Blind the boy was, but pretty as an angel, with a lick of hair falling over his forehead and the purity of his misfortune on his face. The young girls watched him, mired in regret, for such a one as he was not for marrying.

He sang. And I believe the night wind stopped to listen, and the stars come down closer to hear. He sang of a lost love, away in Killarney, her eyes soft as dew, and her lips like a rose. They were to be wedded, but winter come o’er her, and laid his love down ’neath a blanket of snow.

They all wept like children. And then he sang of lonesome Connemara.

They do have tenors, the Irish. I will give them that. But they will never have the power and unity of a Welsh chorus, for, though clannish, they cannot hold together in the clinch, but each will bully his own way. They are a folk for solos. I think it is the way the English beat them down the years, see. For one Englishman will set aside his differences and pull beside another until the dirty work is done, but the Irish would settle their differences first.

But let that bide. The blind boy moved me.

I drew out my handkerchief—for my Mary Myfanwy had accustomed me to the device, and I no longer believed it an affectation—and touched my own eyes.

Then I saw them. Watching me.

Across the big room, lolling about by a trestle where whisky was traded. Chewing little cigars.

Twas the two men I had seen in Kildare’s yard. Night had not improved them.

I raised myself up on my toes to catch the priest’s ear without a needless raising of my voice. He gave me a startled look, as if he had forgotten me completely.

“Those two. By the liquor seller. The big one and the lesser. Who might they be, then?”

He saw them at once. For they were not shy about their staring and did not stop.

“The O’Hara brothers,” Father McCorkle told me. “Napper and Bull. A wise man would cross the street to keep shut o’ them.”

The fiddle called, and broken hairs flew from the bow. The fiddler stamped and sawed his little instrument, and the clapping began. Then the squeezebox joined in, and the round drum fixed the time. In moments, the company set to rollicking again, the sum of their joy beyond the mathematics of Mr. Newton. I lost sight of the brothers O’Hara in the confusion, and did not mind. For I will tell you true: The joy of that music reached me, although it was a raw thing and the makeshift dancehall no fit place for the respectable.

The priest bent down toward me, keeping his eyes on his people.

“This is what I wanted ye to see, Major. Look at them. A Christian man, are ye? Then look ye well. For there before ye are the people He came among.” The priest’s voice twined dreams and anger. “The Magdalene herself, I could point out to ye. And at least a pair o’ thieves. Luke and John that take a poor living from the water. Mary and Martha, unmarried and waiting. And ye’ve had your Judas, haven’t ye? And your innocents slaughtered? Oh, those are the ones He came down to. Not your fine bankers and senators. These are the ones who flocked to Him, who came to hear the Sermon on the Mount. Crawling, they were. Crawling on their bellies, when their weak limbs failed them. To hear the blessed music o’ His words. Craving in their souls for one sight o’ Him. The scorned and despised o’ the world. There are your children o’ Israel.”

He turned his eyes to me then.

“Now tell me, Major Jones. Is this to be their promised land? Or did they trade one bondage for another?”

SEVEN

I MADE NO PROGRESS. A MONTH I STAYED, OR NEARLY. Twas time enough to make nodding acquaintance of the citizens who displayed themselves on Main Street, and to ride the county up and down in Reg’lar John Brent’s sleigh. Sheriff Underwood was an honest man, ready to support me when I had need, yet I came to see that he wished no trouble upon his county and would not go looking for it uninvited. He did send a pair of constables to chop down the tree where Reilly then my effigy had hung. I got to know the place, and my sense of danger lessened with familiarity. I loved the land. Yet the winter was dreary, the days short, and the diet poor.

Although I found their range of interests a marvel and concern, I took comfort amid the Reverend Mr. Morris’s congregation. For their faith was strong, despite the odd notions that crept in among them. And they liked their sacred music, as did I.

Now, I go at the singing of a hymn with a wonderful bellicosity, and blessed are the Welsh in their voices. My vocal expenditures astonished all. Good, humble folk, they could not even meet my eye when I sang out, but only smiled at each other in their delight.

A miracle it was, too, how the pulpit transfigured Mr. Morris. He shed his repetitions to reveal an orator all sharp and clear and true. He preached with a tongue of fire. That greased point of hair quivered, but his eyes steadied upon eternity. He opened the hand of salvation to all, and spoke of light where other men saw darkness. There was much love in the man, and it was revealed in his little chapel.

We are small and foolish creatures. I had all but dismissed Mr. Morris as a silly whack of a fellow before I heard him preach. Thus I learned for the hundredth time that our rash judgements will be rued.

Oh, I learned the back roads and the front pews, the passing faces and the names of farms, the shops and beggar boys. All this I did, but could not crack the Irish.

They have a way of talking grand and saying nothing, those Hibernians. Some look you in the eye but shut their souls. Others will not face you at all, but crab off muttering. I tried politeness and cajolery, appeals to patriotism for their new-gained land, and even threats. I visited their sick with Father McCorkle. I even tried to excite the charity of my fellow Wesleyans on their behalf, but truth be told they found it easier to love a distant slave than a day laborer down in a shanty. Armored in the rectitude of duty, I went into the whisky shabs to see what might be gleaned amid damnation. When that failed, I appealed to those who had climbed up a step—for some of the Irish had painted houses and clothes that asked no mending. But they feared the loss of the little they had gotten, and such were ever glad to see the back of me. The Irish remained as closed to me as the book with seven seals.

I tried to open back doors. At Hammondsport, at the bottom of the lake, I accepted the hospitality of a family of co-religionists while I nosed about, for the hotels were notorious. Now that was a sad little settlement, come near to ruin with the success of Penn Yan across the water. The population had no outlet canal nor railroad of their own, only a troublesome waterfront bunch and a demon scheme of growing grapes for wine. A shame it was, for I have never seen a prettier frame for a village—but, then, I have known many a place poor and beautiful at once. I believe that only prayer kept it from collapse, for the place was wonderful with Methodists.

Northward, in Geneva, I found high society and learning, but no plots. To the south, in Bath—a pretty place—commerce lifted all and even the Irish seemed contented. Elmira was a blue-clad town, with late-recruited soldiers in the streets and bunting on the saloons. Everywhere, I listened in vain for the whispers that

would lead me to Irish plots or to the perpetrators of the murders.

The situation dragged my thoughts back to John Company and India. I do not speak of personal matters now. Twas the feeling of exclusion that was the same. We were as shut out from the world of the Irish as we had been from the schemes of the Hindoo or the Musselman. I found no least hint of rebellion, but well I remembered the Mutiny, and the signs we failed to see then, and the suddenness and slaughter that nearly finished us.

I sensed a darkness in the hills, though I could not find its source.

Look you. I would not pretend to Nellie Kildare’s visions. Yet, there was trouble lurking just under the snows, and I knew it. My forebodings grew as January passed into February without event. For an old soldier knows that spring brings death, not life.

I knew not what to do, and felt a failure. But for a pair of queries, Washington trusted me, with confidence misplaced. Of course, the attentions of the great were elsewhere. Although Mason and Slidell, the Confederates our navy had seized from a British deck, had been handed back, the newspapers warned of London’s surging truculence. The Rebels sought to parley Manchester’s hunger for cotton into an alliance of war. Even the French were sniffing opportunity in Mexico like low mongrels. Meanwhile, we could not fight the war we had. Congress deviled Mr. Lincoln for results, with Mr. Seward damned in a new gazette each week. Twas a dark winter.

“He is not telling all,” you will say. “For he was not quits with the spirit girl, that Nellie.” But there is sad little to report. I went again to visit the Kyle place, where they abided. I took money along. For she had said her father had a hunger for it.

The Great Kildare allowed a conversazione, as he called it. We sat around a little table, the three of us this time, with the curtains drawn against the afternoon. But nothing come of it. The girl remained withdrawn in her father’s presence, and the trance brought not the least hint of spookery. I felt she was resisting. In recompense to me, her father made her do tricks, like calling out a number upon which I concentrated. She brightened long enough to promise I would be happy, but I might have had that of a gypsy at a fair. At last, she fell to coughing. There was a new leanness to her, the sickness hewing her down, and her father quickly led her from the room.

Kildare returned for his money and explained that the spirits would not be moved that day. He pressed upon me a tract he had written on phrenology, along with a little pamphlet on “Swedenborg’s Doctrine of Correspondences.”

I left, with those O’Hara brothers watching from the barn door. As the sleigh pulled off, I heard Kildare’s voice shouting at the girl.

When I went back again they were gone. Mr. Morris, whose admiration for Kildare had not faltered, explained that father and daughter had embarked upon a lyceum tour of a few weeks’ duration. He showed me a handbill. The Kildares would go first to Elmira and Ithaca, then west as far as Erie and Buffalo, finishing with a “spiritualist gala” in Rochester. Young men and women would have their matrimonials predicted by the spirit world, and visions from beyond would startle all.

“He has to do that sort of thing,” the pastor explained, “has to do it. Money for his research, money for his work.”

At the end of January, we had a brilliant thaw. Patches of brown appeared in the fields, and there were birds in the air. If you went abroad at night, you heard the groaning of the ice on the waters. But all was false. With the start of February, winter bullied back. The wind screamed down, and the snows resumed in earnest.

One bitter day, when it was almost too cold for the horses to be out, John Brent drove me down to Himrod’s Corners, where I wished to ask a few questions. In the course of our rides, I learned more from that man than from any other in the county. He had a handsome, even bookish speech when we were alone. If we neared other white people, though, he returned to the jolly dialect of the minstrel, for which he asked my indulgence. Twas the reverse of an Irishman, who will speak his best in your presence, then curse you in his brogue when you go off. But the Negro occupies a peculiar spot in our society, and I think it will take a generation before he is valued as equal to a white man.

Himrod’s Corners was a barren, hardheaded place, a cluster of shacks excused by a meeting of roads. The sole tavern was low, its only patrons farmers going bad. I found no Irish. Still, my queries met silence or diversion, for these were closed-off folk from the glens. We soon began the ride home to Penn Yan.

The team trotted along a ridgeline and I watched a train cross the fallow land, peeling back the snow from the rails before it. Of a sudden, I saw that I had to leave. To return to Washington and make a report. And, perhaps, to recruit my own informer, though the matter lay heavy in my breast.

I will tell you: I was not unselfish in my plans. I would set my departure so that I might have a Saturday night at home, in Pennsylvania, along my way. For I had left a thing undone these last years that wanted doing.

I had tamed the spirits called up by Nellie Kildare, and saw the business clear for a fraud, if still an inexplicable one. The girl’s sickness of body had unbalanced her mind, and her father, the mesmerist, had put things in her thoughts that he had learned on the quiet. How or why I knew not. But answers there would be in time to come, and no spooks or goblins would be found. Meanwhile, an earthly duty lay before me. Painful it would be. But that is the price of duty delayed.

I left Penn Yan in a snowfall.

THE RAILROAD MAKES US THOUGHTFUL. It brings us to one another with remarkable speed, and that is a welcome thing. But along the way it lifts us out of our familiar order. Old notions rise unbidden, and the journey—so eagerly begun—fills with a sense of loss. We feel uprooted, and we are. It is the times. For we live in an age of confusions, unlike the long and simple days of our grandfathers. Our world is a mighty locomotive, hurtling onward, regardless. And war worsens all. What man would not be glad of a little peace?

The train outraced the storm, and when I left the Tenth Avenue depot, all New York City was out in its finery along the avenues. There was bustle. Cheering sparked in the streets at the sight of blue uniforms—which I must say I found a grand and welcome surprise—and I was pressed to avoid the to-do spilling off the curb at each next public house. Fellows tried to fit great schooners of beer into my hand, congratulating me blindly, for too many are the men who associate patriotism with drink. I had to wave my cane to open my path.

With hours to spend before the Pennsylvania train, I walked across town to the district headquarters. Twas staffed by a plump, bewhiskered lot, all merry. They were drinking French champagne. In the middle of the afternoon.

“Haven’t you heard?” a rotund colonel asked in response to my bewilderment. Waving his glass, he surveyed his fellow sybarites in uniform. “The fellow hasn’t heard! Of all things!”

Fort Henry had fallen the day before. Our gunboats beat down its walls even as our army marched upon it. The fortress lay upon a Western river, such as those of which Mick Tyrone had written, and I prayed that my friend was safe. The officers said it was the start of a grand campaign and the beginning of a death blow to the Confederacy.

I found a sober clerk and sent a supplemental telegraphic to Mr. Nicolay, assuring him of my arrival in Washington on Monday. Then I wandered out the time until my train.

A bit too far I wandered. For not all was wealth and patriotic fervor in New York City. I come to slums that made me turn around. Irish, they were. And bitter. The inhabitants cursed me and my uniform by daylight, and on a wall I read a sloven script:

NO IRISH BLOD FOR THER BATTALS!

NO NIGUR KINGS!

FAIRE WAGES!

And a bummer spit on my boots. If insurrection broke out, it would be here. Not in the somnolence of Yates County.

Then there was a block of boys for sale, cheeky and got up fancy.

I fled.

I had to travel by way of Philadelphia, a city with harsh memories for me. From there, I found a space in a mail car going to Reading in the night, an

d, thanks to my uniform and rank, a bunk was granted me on a coaler returning to Pottsville with empty cars.

Twas dark as we clipped the last miles, but I could not sleep. I felt my newfound home rise up around me. The towns and farms of Little Germany slipped behind, and we curved into the water gap, where the Schuylkill washed the valley. Our own canal lay there, and the disordered settlements that had grown up at the landings. All sleeping now. We slowed but did not stop in Schuylkill Haven, home to well-fed Dutchmen, and chugged into Pottsville under a hint of light.

Twas a vigorous place, our Pottsville, built upon anthracite. The yards were quick with shouts when we come in. Our locked wheels squealed on the rails. Switchmen strained over levers. All smelled of ash, but the familiarity was sweet to me.

Despite the hard duty before me, I longed to see my love. For she was my joy. Twas not five weeks since last I had held her to me, yet it seemed a year. My young son drew me, too, but I will tell you truly, not like her.

I feared what was to come.

I had to speak to Hughes the Trains, to insure a place for a Sunday leaving. Meanwhile, I sent a boy along to warn my wife of my arrival. For enough surprises she would have, and to spare.

I TOLD HER ALL. We sent Young John to Mrs. Roberts, next house but one, and let that good woman think what she would. Then we sat in the parlor, for this was a serious matter, and I began straight out. No breakfast I allowed myself, nor pretension that all was well. She wanted but to hold me, my beloved, but I could deceive her no longer, and made her take a place on her proud cushions. I should have made a clean breast of it years back, before we married, when first I come back from India and found her in the garden. But men are weak, and I had been at my weakest then. Now I would be paid back with hard interest for my dishonesty and cowardice.

Darkness at Chancellorsville

Darkness at Chancellorsville Shadows of Glory

Shadows of Glory Red Army

Red Army Cain at Gettysburg

Cain at Gettysburg Valley of the Shadow: A Novel

Valley of the Shadow: A Novel Hell or Richmond

Hell or Richmond The Damned of Petersburg

The Damned of Petersburg The War After Armageddon

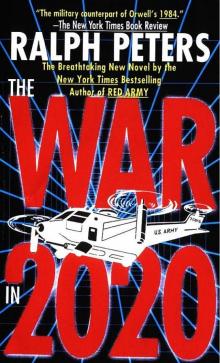

The War After Armageddon The War in 2020

The War in 2020