- Home

- Ralph Peters

The Damned of Petersburg Page 18

The Damned of Petersburg Read online

Page 18

They stayed together now. Without the need for admonition or threat.

Leaving the trees, they faced a worn rail fence, a natural rallying point. His officers rushed the men into battle lines. Just as a passel of Yankees rose out of a swale.

Oates called orders to aim and fire as swiftly as he could spill the words from his mouth. The Yankees were hurrying, too. Halted barely fifty steps off, rifles raised, their thumbs cocked hammers.

Both sides fired in a flurry of moments. Men fell around Oates, some crying out. But blue-bellies dropped like bottles swept from a shelf.

“Give it to them,” he shouted. “Pour it into the suckers.”

Aided by a corporal, Lowther was making his way down the line to Oates. He was clutching his side, where his uniform was darkening under his hand. Lowther crouched as he walked, in immediate pain.

Got him a real wound this time, Oates told himself.

Lowther came near. Oates stepped toward him.

Gasping, Lowther said, “I’m forced to retire … Captain Hill has the Fifteenth.” He closed his eyes, pressing his side, then resumed his speech. “You’re senior man on the field, Oates. You have the command.” Then, with a glint of humanity in his eyes that would trouble Oates, Lowther said, “Good luck.”

Oates shrugged, uncertain. But when Lowther had gone, he felt a raw, child’s urge to shout after him, “I don’t need your luck, not one damn bit.”

The rifle duel continued. But old Alabama was getting the better of it.

Word came from the 15th that Captain Hill was severely wounded and Captain Shaaff had the regiment.

All right, Oates told himself. Shaaff’s good. He had always been Oates’ choice to lead skirmishing parties, a brave and cunning young man.

Captain Strickland of the 48th sidled up and pointed. “Colonel, if we can get around their flank, right over—”

A round cut through Strickland’s hand and wrist, then cut off half an ear. The captain went down in a welter of blood, clutching himself at one spot, then another.

He was right, though. Oates saw it. They didn’t overlap the Yankees much, but it just might be enough. And they wouldn’t expect a charge.

He sent a man to tell Shaaff to hold the 15th in place and keep up the fire. Then he line-walked his Fortykins, telling the men to get ready, they were going to charge and go through the blue-bellies like Paddy went through the whiskey.

Shot in the head, a soldier splashed blood on Oates’ lips. Tasting another man’s life, he shouted:

“Forty-eighth Alabama … charge!”

His men leapt over the fence or just knocked it down. Howling their gritty twist on the Rebel yell. Hosts of insects rose with the charging men.

The waiting Yankee line began to step back. The blue-bellies kept good order at first, but Oates knew that he had them.

“Alabama!” he screamed. Running with his men, pointing with his sword. Wouldn’t be any repeat of Little Round Top this fine day.

The Yankees broke and ran.

Nothing short of high times with a woman came anywhere near the feeling of that charge. As if men were meant to fight as surely as they were fixed to extend their bloodlines.

“Alabama!”

Oates kept his sense, despite himself. Reckoning just how far one torn-down regiment dared go. Faced with a whole Yankee army.

They were nicely on the flank of the blue-bellies, though.

Oates waved surrendering Yankees—the slow, the slightly wounded, and the quitters—to the rear.

“Git on, git along, damn you,” he told the captives.

“Best listen,” a soldier cautioned them.

They came up on a turn-water ditch gone dry. It cut diagonally across the field, as if dug out to serve them.

“Halt! Alabama! Halt! Get down in that ditch!”

A few men who had rushed ahead turned around to rejoin the mass. Shot in the back, one man toppled forward with a look of astonishment.

They were near a branch bottom. Not a hundred yards off, the whupped-on Yankees had rallied on their supports, atop a low hill.

“Y’all stay down now. Use sense. And fire up those blue-bellies over yonder.”

“Get down yourself, Colonel,” a soldier called. “Don’t be no show horse on us.”

All the powers of earth and sky slammed into Oates’ right arm. Spinning him around. The bone cracked loud as a shot. He staggered and cried, “Unhhh.”

Staggering to an apple tree half-fallen into the ditch, he dropped to his knees. Feeling his gone-strange limb, fingering the wound in desperation. Pain hit him like a plank to the back of the head. Unbelievable. No wound he’d suffered, no beating he’d ever taken, had hurt like this. It made him want to roll on the ground and scream.

He closed his eyes and panted like a dog. Struggling to master himself.

Huge pain. Immeasurable.

Through the bloodied mess of his torn sleeve, he felt sharp edges of bone. It made him want to puke.

He knew at once that the arm was lost. The bone had been severed between elbow and shoulder, with the lower arm dangling queer and the bone above the break splintered.

Men gathered around him, more concerned for him than for themselves. Lieutenant Hardwick scurried up and Oates beckoned him closer.

“Tell Captain Wiggenton to take command. I want him to charge that hill, charge it. Right now. They’ll break, they just need a push.”

“Colonel—”

Oates flashed fury. “You go do as I told you, boy.…

“Fetch my sword,” he told another man. “Sheathe it for me. Then you go on, too.”

Wiggenton got the men up finely and charged down through a ravine. Shaking with pain and rage, Oates watched them go.

Finely done, just handsome. His little 48th surged forward in a gray-brown line, uneven but bold, and swept up the other side of the low ground, storming the hill as if they numbered thousands, not weary hundreds.

Oates shouted after them wordlessly, bellowing out his pain and pride at once.

A disordered stream of blue-clad prisoners made their way toward Oates. It was a moment worth clutching for a lifetime.

And him useless. With his favored arm barely attached.

He had to grit his teeth and close his eyes. He’d thought himself a hard man, but the pain meant to defeat him, made him quake.

When he opened his eyes again, he saw Wiggenton fall, right atop that hill. The boy dropped the way a man did who died instantly, a sack of potatoes dropped off of a wagon. Other men went down, too. Madly outnumbered. With the Yankees figuring it out.

Artillery rounds began to strike around them. Grudgingly, his men began to retire. But they brought along their wounded. Despite their numbers, the Yankees only followed at a distance, unwilling to put their paws in that bag of cottonmouths.

When the pitiful remains of his regiment had gathered around him again—exhausted, feverish, panting, made-hard men—Oates told them, “You hold this ditch ’long as you can. Then fall back on the Fifteenth. Hear?”

Lieutenant Joe Hardwick, bleeding himself, said, “Yes, sir. I’ll see to it.” Hardwick was the only officer Oates spotted among the living.

“Just hold this ditch,” Oates repeated. “Got to get this scratch of mine looked after. And I don’t need help from any man.”

He took himself back across the field, in the wake of the Yankee prisoners, with the 15th holding that fence line, firing sweetly into the flank of the blunted Yankee advance.

By God, we did it, Oates realized. We stopped their whole damned army.

He caught a foot in a varmint’s hole and jarred his arm.

Oates howled like a gut-shot dog.

One forty p.m.

Darbytown Road, Union lines

Alfred Howe Terry said, “It’s scandalous, Whitby.”

Birney’s aide sweated and stammered. Bullets punished the air.

Barely containing himself within the bounds permitted a gentleman, Terry spoke a

gain, leaning toward Whitby’s sweat-beleaguered face. “General Birney must send more supports. I’ve just been hit on the flank by two brigades. Two brigades, at least. Struck like a nor’easter. We’re holding, but … oh, for God’s sake, man! Here’s the breakthrough everyone’s pleaded for, crying for it like infants for a teat. Here it is, Whitby! But I can’t hold this ground, let alone push any deeper. Not if I’m not reinforced. That counterattack was just the Rebs’ first gambit, we know their methods. They’ll be piling atop us soon.”

“General Birney’s trying, sir. He’s asked Hancock either to make his attack on the left, or to send us reinforcements.”

“Well, what’s Hancock waiting for? Tell me that. The Johnnies are going to hit us with all they can muster. They must’ve stripped the lines in front of Second Corps, Hancock could stroll to Richmond.”

He was being unfair, he knew. Venting his wrath on Whitby. A staff captain and dogsbody, Whitby couldn’t force anyone to do anything, let alone kick Hancock in the rump. Terry always regretted his rare fits of pique, even as he indulged himself, but this day … it was the chance they’d all been waiting for.…

He heard more Rebel yells.

Two p.m.

Darbytown Road

It would be all right, Lee believed. Hard fighting lay ahead, but it would be all right. Tongues swollen and backs bent, soldiers clad in gray and brown surged past him, going in the proper direction now. The new arrivals eyed him with the old awe, quickening their pace when he spoke a few words to them, his presence a potent drug against their exhaustion.

How did such miracles happen?

An hour before, calamity had loomed. With Chambliss dead and young Girardey, too. Now there was hope reborn, another mercy. The Lord had not abandoned them.

A wave of Carolinians went down the slope at the double-quick, willing their ravaged bodies into battle.

It would be all right, it was going to be all right.

Lee’s heart had troubled him during the day’s misadventures, but the pain had faded.

Walter Taylor returned from pushing men forward. Lee sought to avoid showing favoritism between Taylor, Marshall, and Venable, his staff triumvirate, but Taylor had been with him longest and knew him best.

“Well, Colonel?” Lee asked, voice restored to confidence, even calm.

Taylor drew his mount closer. “We’re awfully thin on the New Market Road now, sir.”

“Yes,” Lee said.

“If Hancock attacks in force…”

“We must repel him,” Lee said. His horse snorted, shifted.

Taylor nodded. “Yes, sir.”

Lee examined the younger man’s tired face. “All war is risk, Colonel Taylor. And caution is failure’s friend.”

Somewhere below, his men cheered. Musketry crackled afresh.

Lee felt drained and old. “It’s a curious business, their failures. Again and again, those people have broken our lines. On that unwelcome day at Spotsylvania. In the mine incident. Here, today. Yet, they falter in the midst of their success.”

Purely military problems always interested Lee. War was mathematics with a cardinal number unknown.

“We’ve faltered, too,” Lee continued. “Though perhaps not so often, or faced with such grand opportunities. It is as if they surprise themselves by winning. And lose confidence.”

“I’ve always thought it a matter of control, sir,” Taylor said. “On both sides. Once the men are well in it, controlling them is impossible. In terms of advanced maneuvers.”

A half-smile graced Lee’s lips as he thought of Mexico, of a lost world’s gorgeous simplicity. “Armies have become too great for our bugles and drums, our flags, Colonel Taylor. Yours is a new and terrible age, I fear.…”

Lee yanked himself from his reverie.

“Come,” he said. “Let us see how things progress.”

“Oh,” Taylor said. “Colonel Oates was wounded. Leading that charge.”

“Yes,” Lee said. “I’ve heard. I hope he’s not hurt too badly.”

Two p.m.

Darbytown Road

“Jesus Christ, stop the horse.”

The mount, spared him by General Field, was being led at a walk, but the movement lit man-breaking pain in Oates’ shattered arm.

The orderly with the reins pulled up the horse.

“Help me down,” Oates ordered.

“Best ride, sir. Looks like you’ve lost yourself a hog’s worth of blood.”

“Help me down, goddamn it. And go easy.”

The orderly—a small man—did his best to guide him groundward while Oates did what he could to comfort his arm.

He hit the earth flat-footed. The burst of pain was spectacular.

Gasping and squeezing his eyes shut to hold back tears, he told the fellow, “You go on now. Take the horse back … my compliments to the general.”

“He told me to stay with—”

“And I’m telling you to git.”

Oates turned back into the flow of ambulatory wounded, skulkers pretending purposes, and couriers doing their best to pound the last muck into dust again.

Oates cradled his arm and walked. How could anything hurt so much? Just a paltry arm. It made no sense.

Walking was better than riding. Merely plumb miserable, rather than downright unbearable. He’d done his work, though. The 15th and 48th both had been all his again. One last time. And they’d busted a few Yankee noses.

As he’d answered General Field’s questions, trying not to break out in yowls of pain, just gutting through it, Bratton’s Brigade and then Benning’s had rushed past, going down like Moses from the mountain to read God’s law to the Golden Calf–licking Yankees.

The horizon seemed to have a mind of its own. Wouldn’t hold still. Men looked like blurs and beasts. His head felt light as a butterfly, but his feet were encased in iron.

Arm. What would he do with one arm? Left one, at that? Learn to write all over again. Other things. Have to learn to balance himself one-armed over a gal. And make her like it.

He warned himself against false hope. Of saving the arm. It was gone. He knew it. Just hanging there a time longer.

His feet and legs rebelled against the journey.

For a moment, Oates went elsewhere. Thinking about plowing a woman one-armed. Swirling in rut smells remembered. An ammunition wagon almost ran him down.

So weak. He’d scorned men who complained of the pain of their wounds, men who wept over themselves. Now he knew.

Wouldn’t shed one tear, though. Would not do it.

He stumbled. Pain-lightning seared him. He made an animal noise instead of words.

At least you can walk, you sorry excuse for a bearded male of the species. ’Least you can walk, you’re not lying dead back there.

But he couldn’t walk. He needed to rest. How far had he walked? He didn’t know. One of so many, so many, on the road.…

Staggering into a poorly barbered orchard, he had the presence of mind to set his back against a tree trunk and ease himself down to the ground. But the pain was everything Satan could wish on a man. Made him want to tear off the shreds of his own arm, then and there.

He might have dozed. Wasn’t sure. Hand on his good shoulder. A little fellow knelt by him. Georgia voiced, not Alabamian.

“I heard you groaning,” he said.

How could he hear anything? With the roaring locomotives in his ears. Battle. Battle of locomotives. See the Yankees run …

“Drink this. You have to help me help you. It’s for the pain.”

Oates felt the tiny bottle against his lips. “No … laudanum…”

“Ain’t laudanum. And you ain’t no blushing belle. You drink this now.”

Oates drank, sucking in the bitterness, and swallowed as best he could. A driblet traced his chin.

“I’m going to bind up that arm now,” the little fellow said. “It’s going to hurt a mite. Got to stop the blood, though.”

“Who … are…”

>

“Assistant surgeon … Georgia…”

“What?”

“Hold still now.”

An artillery shell struck nearby, insulting them with clods of dirt and grit. The assistant surgeon ran high-tail.

“Sumbitch,” Oates muttered. He drifted for a time.

“That’s Colonel Oates.”

“Me…,” Oates said. But he gained lucidity.

Two members of the 15th Alabama’s ambulance contingent stood before him, although there was no least sign of an ambulance. Still, it felt like the finest luck he’d had since a high-stepping filly of a girl had demonstrated her disdain for her lawful husband during a trip that had taken Oates to Montgomery and kept him there for several extra days.

Had two good arms then. What would a fine woman make of a one-armed man? Dusky Sallies wouldn’t mind so much, he didn’t think. Not if it was a white man took to gracing them.

“Colonel … we’re out of everything. Litters, everything. We have to—”

“Good God!” the other man cried. “The Yankees are here!”

Oates snapped to. Clearheaded as could be now. And he saw Yankees, indeed. Hundreds of them. Disarmed and trudging rearward, guarded by a lone sergeant of his Fortykins.

“Help me up.”

“You shouldn’t—”

“Help me up.”

Leaning on one of the men, he stepped toward the road and the parade of prisoners.

Just like to rip that arm right off, get rid of it. Hurt the pain. Take a sharp knife to it. Kill the pain …

“You cut me six strong Yankees out of that pack. And bring ’em here. Pick ’em from those still carrying their trappings.”

The ambulance men did as told. The sergeant herding the prisoners just touched his hat and said, “Whupped ’em good for you, Cunnel.”

Oates stiffened his back, his speech, his heart. “You,” he told a Yankee. “Take down that blanket of yours and roll it out.”

The Yankee didn’t have a mind to argue. They all gawked at his arm.

Can’t look any worse than it feels, Oates thought. Striving with all the gumption he still possessed to remain manly.

Fireworks of pain. A true phenomenon.

“Couple of you boys help me lay on out. Then you’re going to carry me a ways.”

Darkness at Chancellorsville

Darkness at Chancellorsville Shadows of Glory

Shadows of Glory Red Army

Red Army Cain at Gettysburg

Cain at Gettysburg Valley of the Shadow: A Novel

Valley of the Shadow: A Novel Hell or Richmond

Hell or Richmond The Damned of Petersburg

The Damned of Petersburg The War After Armageddon

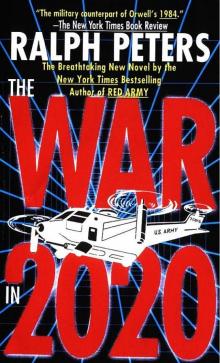

The War After Armageddon The War in 2020

The War in 2020