- Home

- Ralph Peters

Cain at Gettysburg Page 6

Cain at Gettysburg Read online

Page 6

He had been a fool from the start, he saw that now. But Lenore Hutchinson had been favored not only with beauty, she was the daughter of a family of high position, by mountain standards. Calling upon her at her square-built home, he had known desire, but saw respectability. And she had preferred him over his closest rival. He was sure of that. But Lenore never spoke it out loud, for Rafe Granger wore a name still better than hers, even if rumor held that Rafe had already ruined his health as surely as his father had ruined the family fortune. And the Granger boy had time for courting, all the live-long day. Lenore had turned down each of them in turn, enjoying their pain while hinting that, in time, they might ask again. Then the war came. Rafe Granger rode off to join a cousin’s cavalry troop in Virginia. Blake enlisted to match his rival’s gesture.

Not six months into the war, Lenore had wed a banker down in Raleigh, a man who found his duty closer to home. A year thereafter, Mrs. Curran wrote Blake that Lieutenant Rafael Granger had fallen during a cavalry raid in the Valley. And Mrs. Lenore Bascombe had given birth.

And here he was, on the eastern side of a Pennsylvania mountain, waiting to take the lives of other men.

* * *

As the men went hunting sleep in the won’t-quit heat, Colonel Burgwyn came by. What light remained in the heavens caught the gleam of boots shined by his nigger. When the colonel made the rounds, a fight was coming.

Blake both admired and resented Burgwyn. He admired the young man’s flawlessness, his perfection in all things, and the grace with which he demonstrated his bravery. Although he was a North Carolinian, Burgwyn had graduated, young, from the Virginia Military Institute, where he had studied under Jackson and learned his soldiering. After General Pettigrew, Burgwyn was reckoned one of the smartest young men in the South, as clever of mind as he was princely in his carriage, and the regiment was proud of him. The only time any of the men had seen him shaken had been on the march north, when they made camp on the Blue Ridge on a site that was home to a congregation of rattlesnakes. A soldier had killed a snake over five feet long by the colonel’s tent and it clearly troubled Burgwyn just to look at it. But the colonel had steeled himself to take the dead serpent in hand and pretend to admire it.

For all that, Blake could not help feeling that the twenty-one-year-old colonel had known privileges untoward in their extravagance. Blake knew jealousy cheapened a man and he fought it. He even had learned that, to the low-country gentry, the Burgwyn family was of little consequence, as well as suspect for its Northern ties. Yet, when it came down to it, Burgwyn was unmistakably an aristocrat, and Blake wasn’t. A Quaker upbringing, Blake recognized, did not suffice to master the heart’s spite.

After his customary pleasantries, repeated company by company, the boy-colonel grew serious. “You’ll get the formal orders down through your officers, but you might as well hear it now: We’re to be prepared for an early march. And we’ll march light. You’re to leave all knapsacks and blankets for the trains to gather up.” He paused, an actor performing. “There’s a battle waiting down in those plains we saw from the mountaintop. We cannot know precisely where or exactly when that battle will come, but we all know it’s coming.”

The men murmured in agreement. It was a manner of saluting, of acknowledging the colonel, despite the darkness. Blake was glad that Cobb kept his mouth shut.

“Now, I’ve heard the same ribbing you have,” Burgwyn continued. “Our brethren sometimes belittle us because we haven’t had the privilege of sharing in every one of those battles in which they’ve triumphed. They even poke fun at our new uniforms.” He paused to reset his voice, boy-orator as well as boy-colonel. “It’s true that our duty has led us elsewhere at times … but those labors, too, were of the first importance. Still, I know such mockery can sting.”

When Burgwyn cleared his throat, the sound came as sharp as a gunshot. “That mockery will soon end. The Twenty-sixth North Carolina will shatter any doubt as to its valor. I know every man among you will do his part … to bring glory to his regiment and to the good old North State.”

Had the men not been weary, or if they could have seen the colonel’s face, his zeal might have penetrated them. But no cheers answered his speechmaking, only another round of good-natured murmurs, as if the men were sending off a child tasked, just before bedtime, to recite a poem for company.

Accustomed to a richer response to his oratory, the colonel seemed unsure of himself. He lingered.

At last a voice—Hugh Gordon’s—called out, “Don’t you worry none, Colonel. We’ll whip the Yankees proper for you.”

A few more brisk assurances came out of the darkness. And that was all. Blake was baffled by the mood, the unusual lack of connection. He knew these men were spoiling for a fight.

Perhaps, he thought, the whiskey had been just enough to dull them and not enough to quicken them again.

Instead of moving on to the next group of soldiers, the colonel called, “Sergeant Blake? Is Sergeant Thomas Blake there among you?”

“Yes, sir,” Blake answered. He rose and stepped through the thickening darkness, careful of sprawled men.

When he closed on Burgwyn, the colonel asked, “Stroll with me for a minute?”

“Yes, sir. Colonel Burgwyn, I can assure you that the men of this company are ready to fight. They’re as willing as any men on earth.”

“I know that, Sergeant,” Burgwyn said softly. “I know that.” A half-dozen years younger than Blake, he sounded like a father. They reached the road and turned down the slope. Blake waited for the other man to speak.

Black clouds advanced below armies of stars.

“I’d like to hear your side of a matter,” the colonel said, “before I carry it any further. Before I do anything officially.”

The incident at Culpeper Court House leapt to mind, the hot shame of it. The thought that Colonel Burgwyn knew enraged Blake.

“I’m told,” Burgwyn continued, “that you have experience with accounts. That you’re quite the fastidious bookkeeper.”

Blake felt relieved and drained. “I suspect, sir,” he said, struggling to mask the quiver in his voice, “that some of my old customers have been talking on me. A man had to keep clear ledgers back home, if he wanted certain folks to pay their debts.”

“Well, we’re all paying greater debts now,” the colonel said. “I need a new man for regimental headquarters, someone who can keep up with the required reports, with muster figures, pay arrears, all of it. I hoped … that I might interest you in that.”

“No, sir.”

The bluntness startled the colonel. He stopped walking, then turned back up the slope. After giving way to a mounted provost guard, the colonel said, “I suppose you want to be with your men. In the battle ahead. That’s commendable, of course.” He sought convincing words. “But the thing is I need a man I can depend on. Families need to know what’s happened to their loved ones, if they’re dead, wounded, or missing. The army needs this figure, the government that one…” He laughed, but there was no heartiness in it. “One thing I’ve learned, Sergeant Blake, is that an army’s largely what it is on paper. Can’t I persuade you?”

“No, sir.”

Burgwyn stopped again. Blake sensed that they would part now. Some things were clearer in the dark than in the light.

“I could order you to do it,” Burgwyn said. But he laughed again. The sound was as soft as rustling leaves. “Many a man would leap at the chance, you know. A regimental clerk need not go forward.”

“I wouldn’t do it, sir. Even if you ordered me to.”

“That verges on the insubordinate,” the colonel noted. “But may I ask why? Why is it that a man won’t seize such an opportunity? Comradeship? Pride? His sense of a greater cause? You’ve been offered a chance to cheat death, you know. Yet, you declined. Why is that?”

“Fighting’s all I have left,” Blake told him.

* * *

A ghost in the darkness, Cobb appeared. A shadow, a voice.

/> “Din’t I tell you? He has the mark of death on him, sure as a hoor takes your money. You just tell me you don’t feel it, Quaker. Go on.” He snorted. “You going to lie? The way you been lying? About who you are?”

“We all have the mark of death on us,” Blake said.

Cobb cackled. Blake smelled his reek.

“Your Quakers say that?” the foul little man asked. “That what they say? That the Lord has us all marked down for death? Something like that? That’s not what I’m talking about. And you know it.”

“You’re the one who doesn’t know what he’s talking about.” Blake didn’t have the heart for a fight, though. Something nameless weighed on him. “Go off to sleep now. Git.”

To Blake’s relief, the creature moved away. But Cobb wasn’t finished.

“Maybe,” he told Blake in parting, “if you’re right close when the Yankees kill him, you can snatch those pretty boots off him.” He laughed. “Be a tight fit. But you could always sell ’em.”

Blake found his way among the scattered soldiers. Some snored, while others moaned at luckless dreams. Unable to sleep, a few played cards by candlelight, silent but for the percussion of the deck. He came to his spot, or near enough, took off his shoes, rolled up his tunic, and lay down on his back.

Sleep flirted and fled, a cheat. Like Lenore. “Lost Lenore.” He wondered if he had come so far down that he would be capable of killing her. He disbelieved it, but the fact that such a thought could taunt him chilled him. Was it truly about bad blood? Was there a contamination, not of the body but of the soul, that a father could pass down?

His father. Drunk and dead in a ditch. Nor was “dead in a ditch” a mere expression. They found him on a winter’s morn, frozen like a wet coat forgotten outside during a freeze. He was told that his father had been a handsome man, but that was not part of Blake’s collection of memories. He could almost grasp the beauty his mother was reported to have been, but even that required additions of fantasy. Small children do not see their parents so.

He knew the story, for his grandparents, good Quakers, had wielded it as a warning to him.

Thy father drank. He drank away all his gifts, and the Lord had blessed him with many. He broke the hearts of his elders. Thy father was already given to drink when he took thy mother, our daughter, unto him. He had long deserted our meetinghouse, he was a creature plunged into sin. Then he took her, an innocent child, in the night, and only the Lord can say why thy mother went with him. Of course, he couldn’t support her, Thomas. Or thee. He was a feckless man of degraded habits. So thy mother came home to us. With thee. And we took her in. And thee. Despite her sins and defiance. For she was humbled then, humbled and starving. And thou wert thin and pale as a leaf of paper. Dost thou recall what happened next, Thomas? We know thou dost. We know. And thou knowest. They found thy father dead. He lay in a gully in Leesburg, face buried deep in filth, as close to Satan’s abode as he could get. Could any man sink lower? Abandoning wife and child for a bottle of whiskey? Abandoning the Lord and all His mercies? And then thy mother, who would not repent of the sin of taking him unto her, died of the cholera. It was a terrible death, it was a judgment. The wages of sin are death, Thomas. Dost thou understand that?

Loving in their black-cloth way, his grandparents scrutinized him for signs of weakness, but he revealed none. He excelled at his schoolwork, even though he was beaten by the schoolmaster, another excellent Quaker. He was beaten not for what he did, but for who he was. For learning his lessons more quickly than the children of honest parents. Quakers did not believe in violence, but Mr. Harding had beaten him until he could not rise under his own power.

Perhaps it had been the beatings that made him strong. At fourteen, he could have killed the schoolmaster with his bare hands. But he never considered doing so. He accepted his punishment, as if there were justice in it, after all. But his schoolmates were another story.

That fall, on an apple-frost day, the teasing refrain of “Drunk as a monkey and dead in a ditch” was repeated a time too many. He did not behave with the restraint asked of a Quaker. He set upon the largest boy, a Presbyterian sent to the school because it was free, and beat him nearly to death. None of the other students, full of catcalls minutes before, dared intervene. Tom Blake, the drunkard’s son, put his fists to Master Robert Knox so fiercely that he broke his jaw and ribs. The boy had to lie abed into the new year.

His grandparents sent him down to North Carolina, to fellow Quakers. Mr. Curran, white of hair, had put him to work in the store, watching him carefully and locking him into his bedroom when it was time to sleep. But that was all right. No one knew about his father there, so there was no trouble. And the Currans took him to their hearts, the truest Christians he had ever known. They even bore it when, at his maturity, he told them he could no longer go to their meetinghouse, that it wasn’t in his heart. Even after that, Mr. Curran rewarded him by making him part owner of his store. It was a business where no man was cheated, but each man was held to account. Even as Blake grew ever taller and brawnier, as if under a magic spell, the mild work suited him. He looked like a blacksmith, but reveled in pen and ink.

He had nursed so many hopes. And, unlike many a man, he had been willing to work to fulfill them. His energy was boundless. Within himself, he sensed he could do anything. He would make men respect him. He would earn their respect. He would become the pride of his community. He would be envied.

Even after war’s trickery began, he nurtured his dream. After his love married and he learned more about himself than a man should know, he had kept up his hopes for honors. Cobb was right: He had dreamed of becoming a lieutenant and then a captain, as battles took their toll of other men.

Then, on the night they camped near Culpeper Court House, a courier had come by, seeking a drink of water and directions to General Heth. The horseman was the boy he had beaten nearly to death. He recognized Blake immediately. After a moment’s shock, Lieutenant Knox grinned mightily. In a ringing voice, he cried, “Well, if that ain’t Tom goddamned Blake, the town drunk’s boy! This where he ran away to?”

Blake had only turned away, hiding his face, as Adam had done from the Lord on the flight from Eden. He knew then that his dreams were at an end. He had been put in place forever, and the society in which he moved, even that of the stone-pegged hills, would never let him be anyone else. He would never be an officer, not if the war lasted a century. Were he to prosper and grow rich hereafter, he would still be “the drunkard’s son.”

But he had one thing they could not take away. He had the war.

* * *

He dreamed of the golden fields beyond Roznowo. He knew that the old manor house stood just behind his back, shaded by great trees as old as time. Mesmerized by the shimmering world before him, he could not turn. Wheat rose above his father’s knees as they walked the fields together. The northern sky was a peerless blue, and his father’s hand was powerful. But he could not see his father’s face. The man looming so tall was both real and a shadow. A voice called to them. It belonged to his wife, but that couldn’t be. Even in his dream, he knew that his wife could not be present with his father. He had been happy in the dream at first, nearly ecstatic, but confusion marred it. His father had vanished and he could not find his wife, who was lost amid the boundlessness of the fields. He turned around at last to take his bearings, unsure if he were still a boy or grown. The manor house was gone, everything was gone, except the fields of wheat and rye and barley that stretched to infinity. He ran and ran, but could not find a refuge.

Colonel Wlodzimierz Bonawentura Krzyzanowski awoke with a sense of immeasurable loss. The dream had been so rich and deep that it took him a moment to grasp hold of reality. He was not a child now, but a man. His wife was real, and she was in Washington. His father was long dead, the estate long since sold off to pay the family’s debts. His father had fought under Napoleon to revive the Polish state, had served on the plague-ridden march to Moscow and the horrid retreat,

had given all he had, including his slight wealth, for his dream of Poland reborn, and he had failed. He had died in his son’s sixth year, killed by the sale of his ancestral home at the demand of his Poznan creditors, the firm of Wolff, Falk and Levin Koenigsberger.

His dream of the fields beyond Roznowo had haunted Krzyzanowski for as long as he could remember. Those images had pursued him until he no longer knew if they had ever had any substance in reality. The real fields were not endless, of course, although they had stretched far across Pomerania’s flatlands. Did he remember the manor house correctly? Was the image of his father but a fantasy?

The lands girdling Roznowo beckoned him, not the Prussian-regulated streets of Poznan, where an aunt and uncle had raised him along with their own brood after his mother left him, the least healthy of her children, at their door. He had spent most of his life, in Poland and then in America, in cities. Yet, his dreams always returned to rye and barley.

He realized that he had been weeping. Tears often came when he dreamed about his father. He possessed not even a token of the man now, not a saber from Napoleon’s wars, not a button, not a signature on a countersigned paper acknowledging his debts. A world had vanished, its joys hunted to extinction.

His father had died in 1830. The next year, Poland rose again, defying the Russians, Austrians, and Prussians who had enchained her. But the powers aligned against the Poles proved invincible again. Uncles Bogumil and Nemezy, brave men in the family tradition, disappeared into prison. Poverty crept up to their door and slipped in through the windows. Still, his aunt and his last free uncle did as much for him as they did for their own children. So he could grow and make his own futile gestures.

Darkness at Chancellorsville

Darkness at Chancellorsville Shadows of Glory

Shadows of Glory Red Army

Red Army Cain at Gettysburg

Cain at Gettysburg Valley of the Shadow: A Novel

Valley of the Shadow: A Novel Hell or Richmond

Hell or Richmond The Damned of Petersburg

The Damned of Petersburg The War After Armageddon

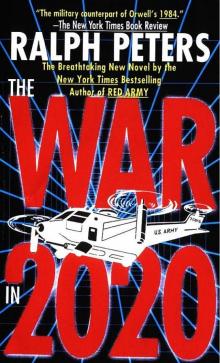

The War After Armageddon The War in 2020

The War in 2020