- Home

- Ralph Peters

Cain at Gettysburg Page 7

Cain at Gettysburg Read online

Page 7

He had been studying mathematics at the Lycée of St. Mary Magdalene when the next Polish rising came, in 1846. For two years, he had lived a secret life as one of Mieroslawski’s underground supporters. But Prussia’s agents knew all. The revolt failed everywhere, most bloodily in Ruthenia, where the Austrians turned Pole against Pole as the Swedes had done two hundred years before. By the time Krakow’s revolutionary government fell, ending yet another dream of freedom, Krzyzanowski was a refugee, keeping low in Hamburg, on his way to exile in America.

His waking dream since then had been to return one day and liberate his country. But the struggle for freedom ran deep in his blood, far deeper than borders could limit. When the slave states seceded to maintain their realm of bondage, he had rushed to New York to raise a volunteer regiment of Polish and German exiles. He endured the infernal politicking for military appointments and the stealing away of recruits by other regiments better supplied with bounty money. He was ready to sacrifice all to show his gratitude to the land that had given him freedom. He was prepared to give his life. Yet, even then he had believed that, one day, he would return to his true fight. In Poland.

He rose from command of a regiment to that of a brigade, riding in front of his ranks, not to their rear. The blood of generations of Polish officers ran in his veins, of winged hussars and Turk-slayers. He had been born to the ways of the battlefield.

Yet, even when his soldiers fought with valor, credit was given sparingly, if at all. The newspapers ridiculed their accents and exaggerated their supposed peculiarities, inventing slurs. Foreigners could not possibly be as brave as the native-born. The winter before, his promotion to brigadier general had been denied after a congressman joked that he wasn’t going to make a general of any man whose name he couldn’t pronounce.

But that humiliation’s impact had been slight compared to what Krzyzanowski discovered about himself as winter muddied its way into spring. Another revolt had broken out in Poland. He had always promised himself that, when the time to fight came again, he would return to the land of his birth. But when the revolution finally erupted, he found that his world had changed. His life was here now, on this soil. His family was here. And the war in which he led a brigade was a war that might be won, not another hopeless, romantic gesture. With or without him, he knew the Poles would lose. His destiny lay here, in this new land.

Then came Chancellorsville. A dozen generations of his ancestors warned him that the corps’ flank was exposed. General Schurz saw it, too. But General Howard, another Bible-bound American Englishman and as proud in his way as a Prussian, dismissed the idea as nonsense: The Rebels were on the other side of the army and the Eleventh Corps might not see action at all.

With General Schurz’s quiet authorization, Krzyzanowski did what little he could. When the Rebels came on, howling like Tartars, his 58th New York, his Polish Legion, and the 26th Wisconsin, the Germans of the Sigel Regiment, were positioned to face them at the Hawkins farm, an island of blue soldiers engulfed by a vast gray sea.

Two regiments could not hold back an attacking army—or halt a fleeing one. His men stood their ground anyway, surprising even Krzyzanowski with their courage. As figures in blue fell rapidly in their slaughter pen, he had needed to plead with the 26th Wisconsin to fall back before it was too late to save the regiment. The Germans had been unwilling to leave their wounded, unwilling to stop killing those who had killed their own. Madly outnumbered, his two dying regiments held for nearly an hour, at a dreadful cost. And as they withdrew, in good order, they fought on for another hour, halting to make successive stands, while thousands of others ran to save their lives.

The newspapers ignored their heroism, writing that the “immigrants” were all cowards.

As he lay in the dark, Krzyzanowski swore he would prove them wrong.

FOUR

June 30

“God awmighty,” Pike Gray said. “What time is it?”

“Time to get up,” Blake told him. “Regimental muster. Out on the road.”

The soldier rose from his sodden blanket. “They letting us time to boil coffee?”

The wetness in the air fell between a drizzle and a mist. Harder rain had soaked them in the night. Ghosts moved among the trees and became men.

“Just bind up your bedroll and get out on the road. We’re to march immediately.”

But they didn’t march immediately. The end-of-month muster was fraught with coughs, complaints, and curses in the darkness. After its completion, officers repeated the order to pile their knapsacks and blankets for the wagons to collect. Any man too ill to march hard was to stay behind.

Few chose to do so.

Talk went around that a big fight lay ahead, chased by a rumor that Grant had been thrashed at Vicksburg and was in retreat. That meant a victory in the days ahead might end the war.

Standing in the mud of the pike as the first light reached them, men ate what they had in their haversacks. Word came down that the march had been delayed again. They could build breakfast fires by the roadside, but had to be ready to fall in at a call.

A tease of rain swept over the trees, coming to nothing. Soldiers coaxed fire from wet sticks, drawing more smoke than flame. Still, the smell of boiling coffee reached Blake and his men.

“Probably just for the officers,” Art Peachum said. A barrel-chested man with scrawny haunches, he was fair-minded and generous for most of his waking hours, but not in the morning. “Their niggers probably been keeping wood dry for ’em.”

Billie Cobb conjured a hint of flame from wood chips. Quiet this morning, as if dreams had oppressed him, he let the other men watch as he worked. Miraculously, the breadth of the fire increased.

“You ain’t completely useless, Cobb,” Hugh Gordon told him.

Cobb just cackled his little laugh. Flames snapped.

“Who’s got the kettle?” Peachum hollered. But the Bunyan twins had already fetched it from the stacks of packs and blankets.

“Probably tell us to fall in, just when she’s ready to boil,” Ollie Wright said. Wright was a man rarely noticed, who slipped around the back of things. Asked once why he rarely said anything, he answered that he rarely had anything to say. Folks left it at that. The army taught most men to get along.

They weren’t a pretty sight that morning, though. For all their new uniforms, the men looked bedraggled in the seeping light. The rain had glued down Tam McMinn’s red hair below his kepi. A good-tempered team of human oxen, the Bunyans slumped against the same wet tree, shoulder near to shoulder. Wright and Ireton crowded near the fire, as if the slight flames might dry clinging garments. Eternally disheveled, Cobb looked little worse than the rest of them now. Misery evened men out.

The fragrance of coffee soon caressed them all.

Lieutenant Devereaux came by, drawn by the aroma. Not all of the officers had darkies to look after them.

The officer attempted to lend his visit weight. “Orders from division,” he told them. “General Heth wants the brigade to search a town down yonder for supplies. Shoes, mostly. We’re just to go there and come back, not stir up a fight.”

“The Yankees might have something to say about that,” Cobb told him. He lifted his face and grinned hideously. “Can’t you feel ’em out there, Lieutenant? They got to be in a killing mood, with us tramping on their shit-pile.”

The lieutenant stiffened. “Oh, I believe we can take care of any Yankees we encounter.”

Somebody had to say it, so Blake did: “Cup of coffee, sir?”

Devereaux smiled. “Why, I call that generous, Sergeant Blake. Don’t mind if I do.”

There was time enough to finish one pot and then another. The men had soldiered long enough not to press their luck beyond that. Except for those taking care of private matters in the woods, they were ready the instant the order rang out to fall in and march down the mountain. The others would catch up quick.

The rain had ceased, but the clouds hung so low it seemed a man could s

tretch on his toes and touch them. Had he tried, the infernal mud would have pulled him back down.

Enough men, horses, and guns had passed over the road in the preceding days to make it a mire. Blake slipped and landed rump-down in the slop, keeping his rifle above him. Mud stew shaped his trousers to his legs when he rose. It added weight.

The other men laughed, but their mirth was no more than a token. Even Cobb refrained from mocking remarks. Before they were off the mountain, every man felt the strain in his ankles and knees.

“This just ain’t no pleasure,” Pike Gray said. “No pleasure at all.”

“Know what my favorite part of all this bumming about was?” Peachum asked. “Crossing the Potomac. Suited me just fine, it truly did. Tearing off every last rag, belly on down, and letting that cool water come on by.”

Hugh Gordon whistled. “Wasn’t that a sight to see, though? A whole bare-assed brigade. Blessed thing that there wasn’t no ladies present.”

Cobb fired off a laugh. “Maybe they would’ve enjoyed it. Get to do some comparing, size things up.”

“Shut up, Cobb,” Peachum said.

Cobb hooted in his broken-throated way. “You don’t think the ladies take an interest? Think they’re all pretty statues, set high up to decorate a house? That what y’all think?”

“Cobb doesn’t know any ladies,” Corporal Ireton said. “Never did, and likely never will.”

At that, Cobb fell silent and marched apart without leaving the ranks. It was told on him that he’d had a wife he doted on, but that she’d run away some years before.

“I expect we’ve all known a lady or two,” Blake said. “Cobb included.” He turned the conversation. “You, James Bunyan. You feeling right today?”

“Fit as a fiddle, Sergeant. I just—”

“Then pick up your feet. You’re plowing a row, boy.”

“Yes, Sergeant Blake.”

They entered a tidy settlement, but the band had not been sent up to play this morning. That told the men things were serious indeed.

Word came down the line that the place was called Cashtown. A fine-looking tavern graced the busy street. Officers milled in front of it. Rain teased.

Beyond the town, soldiers from other brigades pecked at camp duties, standing down for the day and leaving the marching to Pettigrew’s lot. Farther on lay fields of wheat and oats that begged to be harvested as soon as the weather dried. For all the talk of battle, the world seemed sweetly calm.

The column halted. The march did not resume quickly, but the men were not allowed to fall out on the roadside. Captain Carr rode forward, then returned. Word filed back that they’d reached the forward picket line and Colonel Pettigrew was dickering with the commander about something. Beyond lay an unknown world and, somewhere, an army clad in blue.

When the march began again, the rain did, too.

* * *

Meade stepped out of the tent. He had dressed down Butterfield again. The man could not keep up with the new regimen. Nonetheless, Meade’s confidence had grown. The army, like an unruly child, just needed a firm hand.

He could feel the blue beast out there, drawing itself together, the various corps approaching positions from which they could march quickly to the battlefield he chose. Since taking command, he had been pleasantly surprised at the support from his corps commanders, who so recently had been his peers. Even Sickles appeared to be showing more vigor.

The trick of it was to keep control, to avoid treating the corps as loose odds and ends, as Hooker had done at Chancellorsville. The army had to fight as an army. Its parts had to converge toward one goal.

A few raindrops fell, dull thuds on Meade’s slouch hat. But it was only a skirmish, not an attack.

General Hunt, the army’s chief of artillery, rode up, followed by two aides in gunner’s jackets. Soldiers hastened out of the way of the hoof-splash.

“Well, Henry?” Meade asked as Hunt tossed his reins to a captain just out of the saddle.

Face spattered with mud, Hunt got right to the point. “The Pipe Creek line’s the true place, you were right. The south banks generally run higher and steeper, and the bridges are easy to cover. Plenty of fords, but they’ll slow an attacker nicely.”

“General Warren’s of the same opinion,” Meade told him. “I’ve sent him back out to survey specific positions.”

Hunt pulled off his riding gloves and wiped his eyes. “Damned good place to fight, sir. If we can bring Lee to attack us on that line, it could be Fredericksburg in reverse. And we’d be well positioned for a pursuit. Lee would have no recourse but to retreat due west. And he couldn’t defend those passes, they’re easy to flank. He’d either have to stand and fight again, or risk what remained of his army in a pell-mell run.”

Meade nodded. “The trick is drawing him back into Maryland. But I think it can be done.”

“Any further word on Lee’s position?”

“Still stretched out on the roads. Buford reported infantry and artillery west of Gettysburg this morning. Hill’s men.” Meade sighed. He’d had only brief snatches of sleep since assuming command and felt bone weary. But there was no time to rest. “As soon as I learn more details of the ground from Warren, we’ll get orders out. If Butterfield’s up to the simple task of copying. But plan on the Pipe Creek line for your guns, Henry. Meanwhile, Buford can watch Hill, and John Reynolds can move the First and Eleventh Corps to Gettysburg tomorrow to cover our flank. While I move the rest of the army into position.”

Hunt pulled his riding gloves back on, another tired man. But a game one. He’d be off now to inspect his ammunition trains.

“Headquarters staying here?” the artilleryman asked. “This where I’ll find you?”

Meade shook his head. A few drops of rainwater fled his hat brim. “I’ve ordered a move to Taneytown. I want every subordinate able to reach me quickly. I won’t have the dilatory communications we all suffered under Hooker.”

A serious man, Hunt surprised Meade with a smile. Perhaps he was thinking fondly of his guns. “We’ll fight at Pipe Creek, then?”

“Pipe Creek,” Meade assured him.

* * *

Lee read the dispatch the courier had delivered, then raised his eyes to Longstreet and to Hill.

“They chose George Meade, not Reynolds,” the old man said. He seemed uncharacteristically surprised. And not especially pleased. But, then, he had been out of sorts for days. Waiting with growing impatience for Stuart to materialize. The staff’s jollity earlier that morning had been a mild rebellion against Lee’s dourness.

“Well, that’s fine,” General Hill said. Despite his grin, the gaunt Virginian looked uncomfortable in his own skin. Afflicted. Clots of brown hair rested on his shoulders and the red calico shirt he affected made him resemble a scarecrow. But his eyes burned. “Meade’s an engineer. He’ll be timid.”

“He wasn’t timid at Fredericksburg,” Longstreet said.

“I’m an engineer myself, gentlemen,” Lee reminded them. “Perhaps you will not abuse the discipline too harshly.”

Longstreet thought that would close the topic, but Lee mused, “General Meade will commit no blunder in my front … and if I make one, he will make haste to take advantage of it.”

“We’ll lick George Meade,” Powell Hill said. He was a valiant, volatile man.

Lee half-turned away. “I must know where those people are. I must know what Meade intends.” He wheeled on Longstreet, ignoring Hill. “It’s taken two days for us to learn this news about General Meade. Of what else are we in ignorance?”

Say it, Longstreet thought. Go ahead. Admit that Stuart has let you down. Get it off your chest.

Lee mastered himself and addressed his next words to Hill. “General, I must know immediately, if you find those people to your front. Meade may not move swiftly, but he will move surely.”

“Nothing out there but a few militia,” Hill assured him. “Been quiet.”

Lee dropped the dispatch on a camp des

k set up in the open air. “Those people will be fighting on their own soil now. That cannot help but steady their morale. When we find them, we must defeat them without delay. They must not have further opportunity to rally.”

The old man turned to Hill again and continued. “We cannot afford chance encounters, General Hill. No one is to bring on a general engagement until this army is concentrated. When our blow lands, it must be sudden, and it must be decisive.”

Longstreet chose not to speak. He had made his argument for choosing good ground and forcing the Federals to do the attacking. And he would make the argument again. But not in front of Hill. He could not be frank in front of the other man.

Hill adjusted his spattered britches, bothered by what they contained.

“In two days’ time,” Lee said, as if to himself, “this army will be together again. Then we shall see to those people.”

* * *

As they marched beyond the picket line, a Virginia regiment joined the column behind them. The pike led through more good country. Rain kept flirting. The pace General Pettigrew set the brigade went hard.

“Swear to God, I smell Yankees,” Peachum said.

“That’s just old Cobb there,” Ireton told him.

Cobb didn’t respond beyond rubbing the sores on his nose. He was still sour. Blake wondered what else there once might have been to the man. Besides the woman who had run off long ago. There were blank pages in Cobb’s history.

After covering several miles, the column halted again. A courier galloped past, headed rearward. It was impossible to move fast enough and far enough to avoid all the mud kicked up by his mount’s hooves.

“Sumbitch,” Cobb said. Evidently, he was speaking again.

Minutes later, a civilian on horseback followed the courier’s path, though at an easier pace.

Blake saw Lieutenant Colonel Lane, the regiment’s second in command, trot back to confer with his company commanders. Lane was a hard man, with no time for nonsense. He looked hacked from oak, then painted in shades of brown. He was not a high gentleman born. Blake trusted him.

Darkness at Chancellorsville

Darkness at Chancellorsville Shadows of Glory

Shadows of Glory Red Army

Red Army Cain at Gettysburg

Cain at Gettysburg Valley of the Shadow: A Novel

Valley of the Shadow: A Novel Hell or Richmond

Hell or Richmond The Damned of Petersburg

The Damned of Petersburg The War After Armageddon

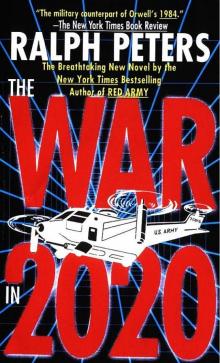

The War After Armageddon The War in 2020

The War in 2020